A soldier’s tale

Horace Archibald Davies was born to Moses and Catherine on 3 April 1895 in Normanton, north Queensland, Australia.[1] This little town boomed briefly as a port following the discovery of gold nearby at Croydon in the 1880s, but by 1911 the population was down to about 541 people and falling.[2] Normanton is a long way from anywhere.

The Davies family, 1912. Horace is the tallest standing at the back. Author’s collection.

Horace was the eldest child of his family, with a sister and three brothers. He was nine years younger than his cousin, my grandmother.

When war was declared in 1914, he was 19 years old and a farmhand at Gordonvale, not far from Cairns. Horace travelled to Brisbane to sign up at Enoggera on 24 December.[3] On 13 February 1915 he and his mates of the 2nd reinforcements, 9th Battalion, Australian Infantry Force (AIF), boarded the Seang-Bee in Brisbane, on their way to Egypt.[4] He was part of the now-legendary ANZAC force, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, about to forge the will of a young nation in an awful bloodbath called Gallipoli.[5]

The unit war diary of the 9th Battalion states that these reinforcements were received on 10 April 1915 while on the island of Lemnos in Greece.[6] The 9th Battalion was the first ashore at Gallipoli at 4:30 am on 25th April 1915.[7] Horace was part of history, struggling ashore through chest-high water as the Turkish bullets whizzed past his head.

His life in remote north Queensland made him robust and tough but did not expose him to the many ailments of a more crowded population. By May he was returned to hospital in Egypt with the measles. He must have had quite a dose, as it was six weeks before he was discharged to convalescent camp. Ten days later he was on the Expeditionary Force Transport the Scotian back to the hell of Gallipoli, rejoining his unit on 10 July.[8] He was just in time to participate in the dreadful “August push”, the concerted attempt to overwhelm the Turks that failed dismally.

Horace survived August but the heat, lack of fresh water, primitive sanitation and mental strain was impacting the troops badly and Horace was one of many – about thirty per cent were unfit for duty – to succumb to dysentery or enteric fever (now known as typhoid fever).[9] By late September he was on a hospital ship, the Dunluce Castle, to Malta where the military hospitals did their best to return him to health. After nine weeks he was described as “debilitated, weak and still suffers from diarrhoea.” The prescription was six months at home.

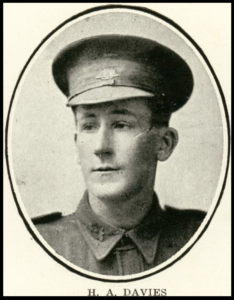

Portrait of H.A.Davies. State Library of Queensland, https://collections.slq.qld.gov.au/viewer/IE1109167

Horace travelled from Malta to Egypt on the Essequibo, then from Suez to Australia on the second voyage of the No 2 Hospital Ship Kanowna. What joy he must have felt to disembark at the military hospital in Brisbane, where family could visit and fresh fruit, vegetables, good meat, and clean water were everyday occurrences instead of distant dreams. What a difference his family must have seen, the fresh-faced 19-year-old now an ill, battle-hardened soldier of 21.

Horace’s younger brother Herbert Montague Davies joined up on 16 February 1917, back home in Cairns – was he inspired by his brother’s example? Herbert arrived on the western front to fight with the 41st Battalion of the AIF in late 1917, returning home in 1919.[10]

By the end of May 1916, Horace was once again fit for duty and returned to barracks. It wasn’t until the end of December 1916 that Horace once again embarked for Europe on the Demosthenes, this time with the 18th Rifles of the 26th Battalion. With his experience, he was made a Sergeant V.O. (voyage only) on the ship.

It seemed that Horace had demonstrated his leadership ability, as for the next few months he was made Acting Corporal E.D.P. (extra duties pay) several times. This first occurred when he arrived in England on 3 March 1917 but two days later he was once again in hospital as a Private, this time with the mumps. He had less than two weeks of illness, so one wonders if he was in fact ill on the ship.

Five weeks at junior officer training college was waiting for him, once again as Acting Corporal E.D.P. Completing his training on 5 May, perhaps he enjoyed some leave with a chance to celebrate his twenty-second birthday. On proceeding overseas on 21 May he reverted to Private, shipping out from Southampton to Le Havre in France. Arriving at the Divisional Base at Le Havre on 23 May, by 25 May he was again Acting Corporal E. D. P. until he left to rejoin his Battalion somewhere in France as Private on 11 June.

On 19 August 1917 Horace was appointed Lance Corporal, still in France. Within two months the 26th Battalion was in Belgium, and on 25 September he was made temporary Corporal as the war took its toll on those who led. He replaced Corporal Charles Stanley Emmons from Brisbane, who had been sent for training, having been made temporary Corporal on 5 May.[11]

Horace had nine days at this rank, days of the battle for Polygon Wood, climaxing for Horace in the Battle of Broodseinde Ridge where he took a shrapnel hit to his right arm, wounding it severely.[12] Wounded on October 4th, it was five days before Horace reached Horton Hospital at Epsom in Surrey, England. After a further five days at Horton, he was briefly transferred to a hospital in Dartford, Kent before being discharged to a recuperation camp near Hurdcott, Wiltshire. He spent December and January in England, recovering.

Horace could heal knowing that the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Australian Divisions captured Broodseinde Ridge the day he was wounded – the 26th Battalion being part of the 2nd Division. His injury kept him out of the battle of Passchendaele. The first assault on this village took place on 12 October 1917 and the battle became infamous for the scale of casualties and for the mud.[13]

On 13 February Horace rejoined his battalion in Belgium.

On 14 July 1918, the 26th Battalion captured the first German tank to fall into Allied hands – No. 506 Mephisto, in Monument Wood near Villers-Bretonneux.[14] This tank, the only one of its kind that survived, is now in the Queensland Museum.

On 17 July 1918, Lance Corporal Horace Archibald Davies was killed in action at Villers-Bretonneux on the Somme River, aged 23. The unit diary entry for that day says

“…it was only the determined attack of the men that caused the enemy to clear out and leave his M.G.s [machine guns] before doing one quarter the damage he might have done had the attack been half-hearted. As it was about 30 casualties were inflicted…”[15]

Horace lies buried in the Adelaide Cemetery, two and a half miles from where he fell.

His death is commemorated by memorials in the Cairns cemetery and the Albany Creek Memorial Park in Brisbane.

Lest we forget.

[1] Queensland Registrar General, Birth Register (pdf copy image), entry for Horace Archibald Davies, 1895, Registration number C1149.

[2] Queensland Places, “Normanton”, Centre for the Government of Queensland (https://web.archive.org/web/20110305060456/http://www.queenslandplaces.com.au/normanton; accessed 6 May 2024).

[3] Details of Horace’s service throughout this article are sourced from National Archives of Australia: B2455, Davies H A (https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/; accessed 16 August 2018).

[4] Unofficial history of the Australian & New Zealand Armed Services, “9th Battalion AIF (Qld)” (http://www.diggerhistory.info/pages-conflicts-periods/ww1/1aif/1div/03bde/9th_battalion_aif.htm; accessed 6 May 2024).

[5] State Library of Queensland, “Pte. H.A. Davies, one of the soldiers photographed in The Queenslander Pictorial, supplement to The Queenslander, 1915.” digital image, 19 June 1915, page 25 (https://collections.slq.qld.gov.au/viewer/IE1109167; accessed 16 August 2018).

[6] Australian War Memorial, “Australian Imperial Force unit war diaries, 1914-18 war”, AWM4 23/26/4 – March 1915, page 7, digital image (https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/RCDIG1003183/; accessed 6 May 2024).

[7] Australian War Memorial, 9th Australian Infantry Battalion (https://www.awm.gov.au/unit/U51449/; accessed 6 May 2024).

[8] Historical RFA, “Requisitioned Auxiliary – Scotian”, Historicalrfa.org (https://web.archive.org/web/20160504162034/http://www.historicalrfa.org/requisitioned-auxiliaries/176-requisitioned-auxiliaries-s/1452-requisitioned-auxiliary-scotian; accessed 7 May 2024).

[9] Great War Forum, “Dysentry”, 30 July 2014 (https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/215223-dysentry/; accessed 6 May 2024).

[10] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Davies H M (https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/; accessed 16 August 2018).

[11] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Emmons C S (https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/; accessed 16 August 2018).

[12] Australian War Memorial, Battle of Broodseinde Ridge, Australian War Memorial military events (https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/E84313; accessed 6 May 2024).

[13] Australian War Memorial, Battle of Passchendaele (Third Ypres) (https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/blog/battle-of-passchendaele-third-ypres; accessed 6 May 2024).

[14] Australian War Memorial, 26th Australian Infantry Battalion (https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/U51466; accessed 16 August 2018).

[15] Australian War Memorial, “Australian Imperial Force unit war diaries, 1914-18 war”, AWM4 23/26/43 – July 1918, page 12, digital image (https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/RCDIG1005304/; accessed 16 August 2018).

This is such an inspiring but tragic story. You drew me into Horace’s life and I wanted him to survive. You have written and researched his life so well. I was impressed with your citations. Always professional. Thankyou Charlotte.

I’m so glad you enjoyed Horace’s story. He’s a hero of mine. So sad that he died, so near the end of the war. Thank you for your kind comments about my writing and citations. Charlotte

Such a sad story, Charlotte, but a very interesting read. I have followed some of the history of the 9th Bn AIF so was interested to read that Horace was part of that battalion at Gallipoli and later spent 5 weeks at the junior officer training college. What a pity he did not survive the war. He may have become a great leader. Interesting reference to the Mephisto tank captured by the 26th Bn.

Thanks Ross. Yes, Horace seemed a special person and one of so many whose potential was not to be realised. I’d love to know if he had any role in Mephiso’s capture but it seems it was probably men he knew rather than he himself. Charlotte