Convict tattoos

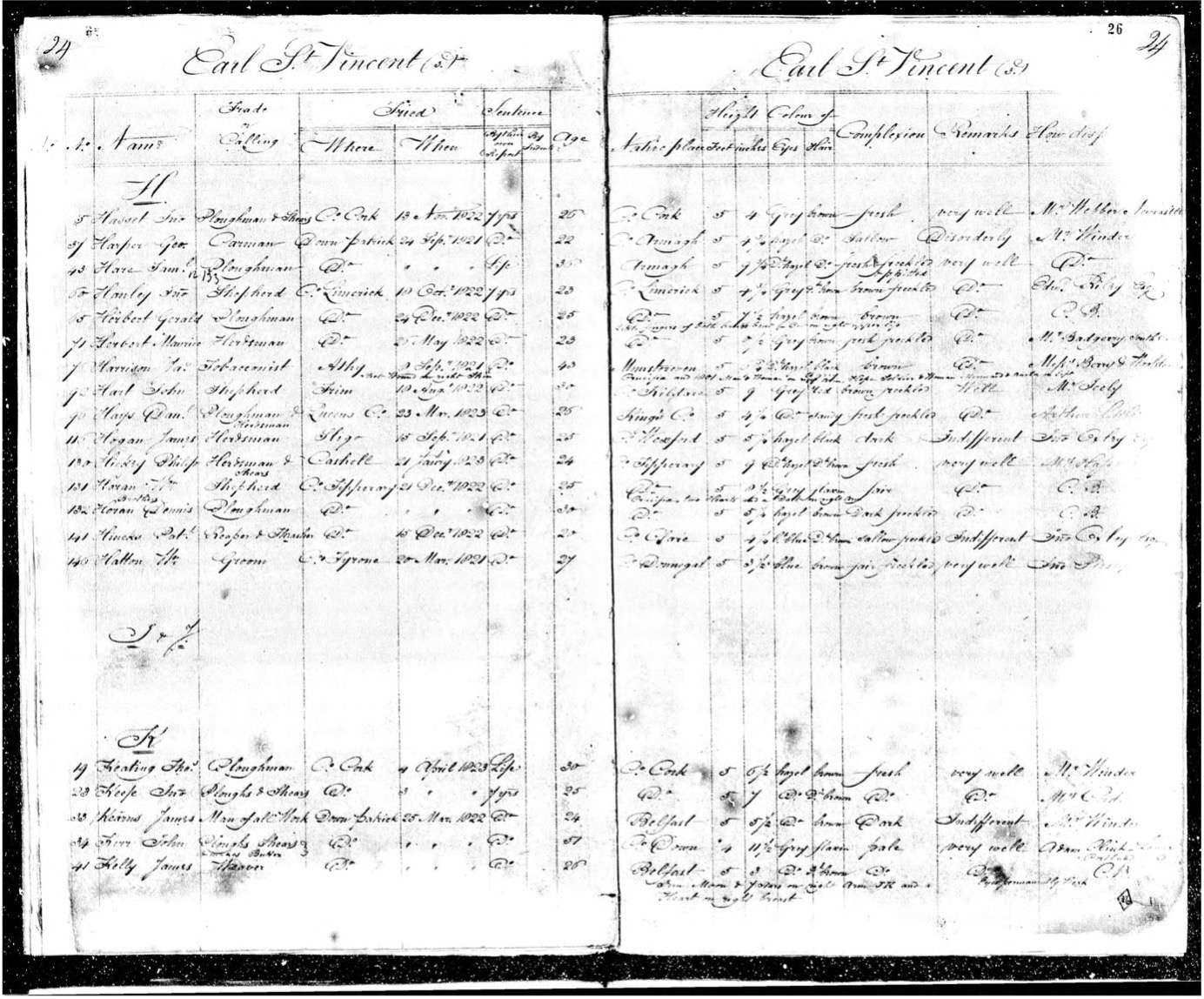

It was quite a few years ago that I first encountered the Irish convict, James Harrison. He was found guilty of stealing copper and sentenced to seven years transportation to Australia. On his arrival in 1823, along with other details, his convict indent recorded that he had several tattoos. There was a crucifix, ‘1801’ and the words ‘man and woman’ on his right arm. On his left arm were the words hope and soldier and the picture of a woman, a mermaid and an anchor.[1] [2]

Convict Indent for James Harrison New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents, 1788-1842 for James Harrison, Online publication- Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Inc.

I couldn’t find a lot of information about tattoos at the time, but I made some assumptions. I thought that James must have been a sailor, because of the anchor, mermaid and the crucifix. I had read that sailors often had a crucifix tattoo to signify they were Christian so they could be properly buried if needed. I also wondered if he might have been a smuggler because of the crime for which he was transported and his profession. His crime was stealing copper. If the copper was goods, it may have been stolen from a warehouse or even a ship.[3] His profession, stated on the indent papers and his Certificate of Freedom, was a tobacconist. I thought it likely that tobacco might be a product worth smuggling. It seems that tobacco was one of the few imported commodities which was widely consumed in early nineteenth century Ireland. According to a witness speaking to a revenue commissioner’s inquiry about tobacco in 1823: ‘The lower orders … are the chief consumers, both men and women have great delight in it, and as a question of feeling it would be a good thing to give it them cheap, it is such a source of comfort to them.’[4]

Memorial of 1798 rebellion. Main Street, Monastrevin. https://www.irishwarmemorials.ie

I also wondered whether James had been a soldier at some time. Or perhaps the soldier tattoo was associated with the tattoo of year 1801. When I researched his birthplace, Monasterevin in Ireland, I found it had been the place of one of the battles of the 1798 rebellion against British rule. In response of this rebellion, changes to the governance of Ireland were legislated under the authority of the Acts of Union 1800 (enacted from January 1801) decreed Ireland and Great Britain to be a single kingdom, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.[5] Five yeomen were killed and four were wounded during the battle at Monasterevin.[6] Rebels who were taken alive, being regarded as traitors to the Crown, were not treated as prisoners of war but were executed, usually by hanging.[7] Regardless of whether the 18-year-old James Harrison was involved in the battle, these events most likely had an impact on him.[8]

The man and woman tattoos, I assumed referred to loved ones and the hope tattoo seemed self-explanatory. When I recently found a very informative book describing Australian convict tattoos, I thought I’d revisit James Harrison.

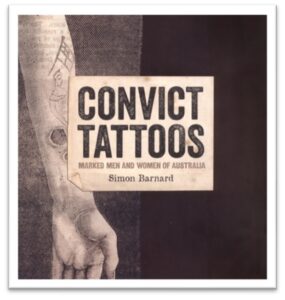

Simon Barnard examined, collated and analysed the physical descriptions and tattoo records of thousands of men and women transported to Australia between 1823 and 1853. He notes that around a quarter of the convicts sent to Australia had at least one tattoo. The tattoos were different than those of today. The tattooist was called a ‘pricker’. The most common dyes were gunpowder and charcoal, but China-ink and Indian-ink were also used. A needle, or two or more needles bound together, was repeatedly dipped in the ink, and with the skin drawn tight, pricked over a previously drawn outline to a depth that penetrated the outer layer of skin. Water, saliva or urine was used to dilute the ink, clean the needle and wash off the blood. [9]

Cover of book; Convict Tattoos: marked men and women of Australia, written and illustrated by Simon Barnard. 2016.

The first part of the book provides the context and gives a comprehensive overview of convict tattoos and explanations for many of the more common tattoo motifs and examples from details of actual convicts as reported in newspapers and other convict records.

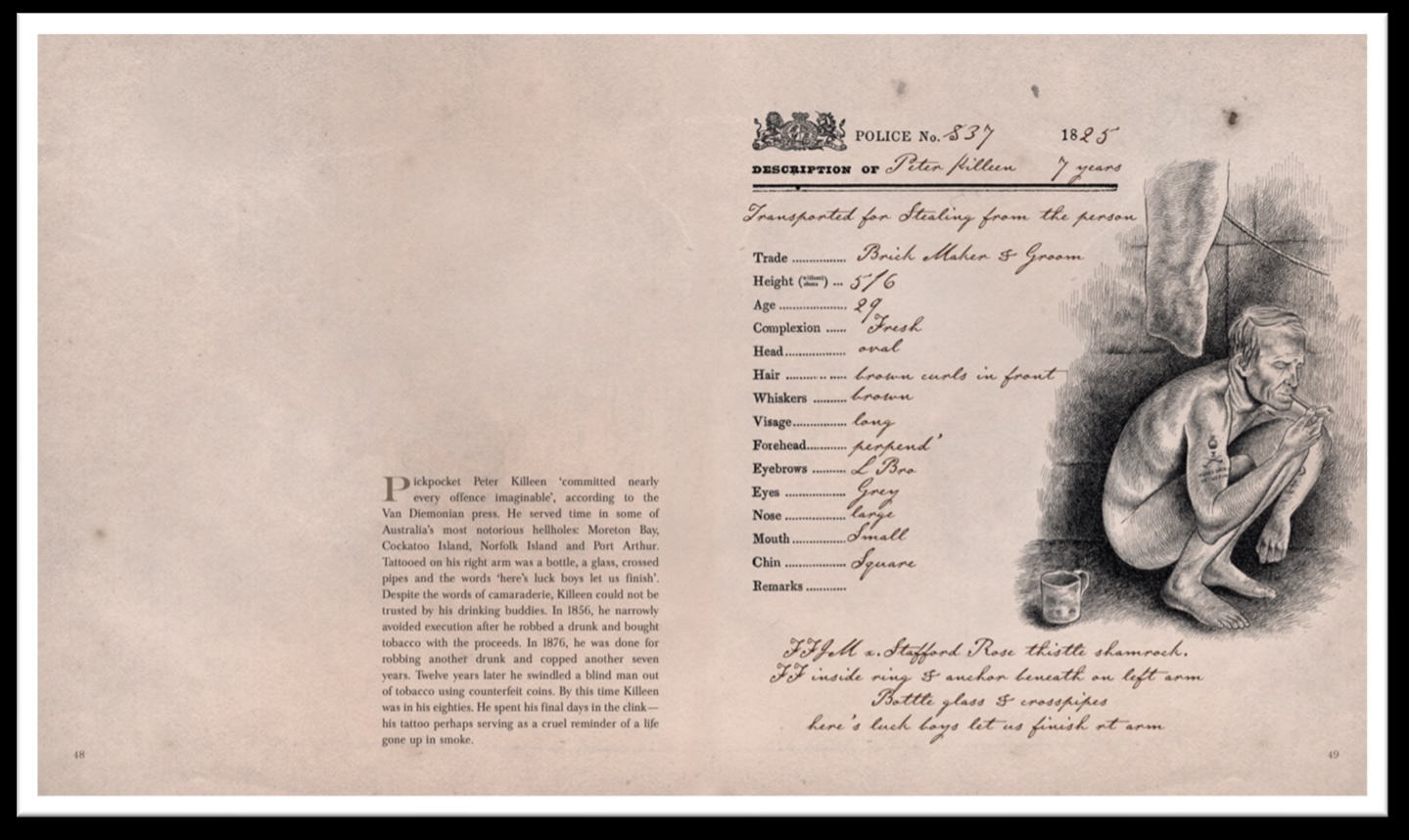

The last half of the book is an overview of specific tattoos. When I looked up the tattoos recorded for James, I found some additional information. In relation to the crucifix, the book confirms that religious tattoos expressed the bearer’s beliefs, but provides the added meanings of redemption, absolution and parallel suffering. Some people believed that the crucifix provided protection. As I had surmised, it seems that for transported convicts, the man and woman, or Adam and Eve motif was particularly potent reminder of loved ones left behind, particularly as a transportation sentence frequently resulted in permanent exile. I did not realise that the anchor was an ancient symbol of hope. Nor that it was the most popular of all tattoo motifs, accounting for nearly ten percent of male convict tattoos. Likewise, the mermaid, celebrated for their beauty and melodious voices, but feared for their habit of luring sailors to watery graves, may have been of particular significance to convicts who longed for their loved ones, felt betrayed by accomplices or misjudged by authority. About four percent of tattooed male convicts bore images of mermaids.

Example of details of convict from book Convict Tattoos: marked men and women of Australia, written and illustrated by Simon Barnard. 2016.

James’ tattoos provide a glimpse of what James’ life may have been behind the historical record. It’s possible he was a sailor because of the crucifix, anchor and mermaid. Perhaps the mermaid also signified betrayal. The word soldier and 1801 may be reminders of adversities he had already overcome. The word hope could indicate that he remained hopeful in the face of adversity, as too perhaps the man and woman, reminding him of those who were important to him, his reason to be hopeful. I’ll never know for sure, but it seems these motifs have meaning and I believe that marking himself as he has, must indicate he was a man of very strong feelings.

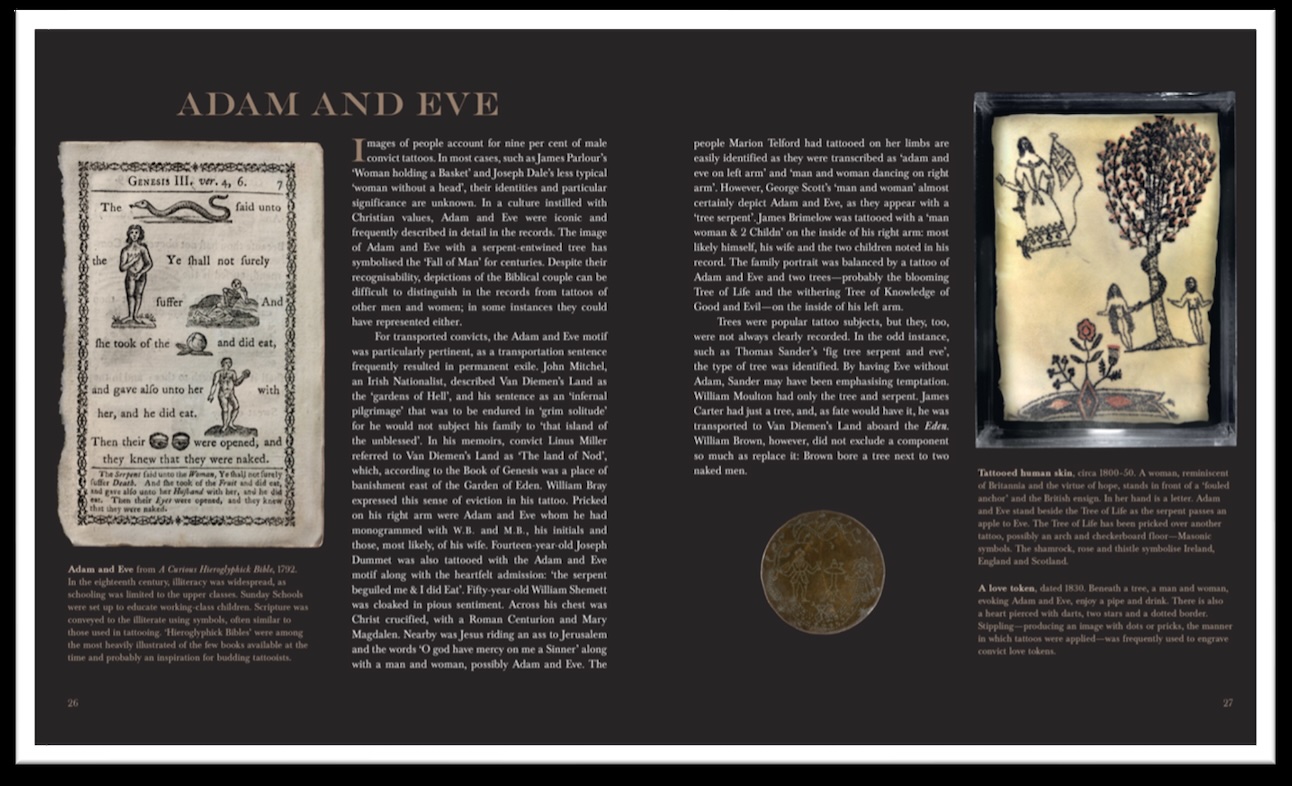

Description of Adam and Eve motifs from Convict Tattoos: marked men and women of Australia, written and illustrated by Simon Barnard. 2016.

[1] State Archives NSW; Series: NRS 12188; Item: [4/4009A]; Microfiche: 653 (Man & Woman were also on his right arm and on his left arm were hope, soldier, woman, mermaid and anchor)

[2] New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents, 1788-1842 for James Harrison, Online publication- Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Inc.,

[3] http://www.21crimes.com Crime number 13: Stealing iron, lead or copper, or buying/receiving

[4] Wakefield, An Account of Ireland (London, 1812) vol. 2, p. 31. Tenth Report of the Commissioners of Enquiry into the Revenue Arising in Ireland, (Brit. Pari. Papers, 1824, X), p. 770. Cited in Bielenberg, A., & Johnson, D. (1998). The Production and Consumption of Tobacco in Ireland, 1800-1914. Irish Economic and Social History, 25, 1–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24341016

[5] Britain, Ireland, and the disastrous 1801 Act of Union, Marjie Bloy, Ph. D., Senior Research Fellow, the Victorian Web www.victorianweb.org/history/ireland1.html viewed September 2016.

[6] http://kildarelocalhistory.ie/1798-rebellion/rebellion-towns-villages/monasterevin/

[7] p. 113 “Revolution, Counter-Revolution and Union” (Cambridge University Press, 2000) Ed. Jim Smyth ISBN 0-521-66109-9

[8] New South Wales Australia, Certificates of Freedom 1827-1867. Certificate 28/806 for James Harrison, 11 September 1828. Online publication- Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Inc., Born in Monsterevin in 1780 (Harrison James Certificate of Freedom, 1828).

[9] Barnard, S. (2016). Convict tattoos : marked men and women of Australia / written and illustrated by Simon Barnard. Text Publishing.

Very good background information, I am distantly related to James. Thank you, Maree

Re-inserted by Blogs Admin after website malfunction.

Hi Maree,

Thanks. I found James fascinating. I had thought I was related to him but have discovered that my grandfather was not the biological son of the man we thought was his father. However I had done a lot of research into these earlier convict families I’ve also written a blog about James’ wife, Catherine Hawe/Howe (April 2023). They are still on my ancestry tree. Regards Yvonne

Re-inserted by Blogs Admin after website malfunction.