Researching women in early colonial NSW

This Court has duly considered the evidence, both for and against you, and judges that you are not guilty of maliciously killing the deceased, Robert Morrow, the basis for the crime of wilful murder. The Court does find you guilty of the aggravated and felonious killing and slaying of the deceased.

…..

You, Eleanor Irwin, have conducted yourself through this unhappy incident with great violence; highly unbecoming your sex. You will be confined in His Majesty’s Gaol at Parramatta for the term of two years.

On first reading these lines about my three times great-grandmother, spoken by the New South Wales Judge Advocate Ellis Bent in June 1814, I was startled, but also realised that I had found a ‘goldmine’ in researching the life of my ancestor, Honor Connor/Eleanor Irwin/Ellen Skuthorp.[1] Eleanor had arrived free with her convicted husband five years earlier and each was found guilty of the same crime.

As family historians we have experienced the challenges in researching the women among our ancestors. So the hints provided by Ross Hansen in his GSQ blog of 4th November 2024, ‘Now What about the Women? – Enjoying the Next Genealogy Journey’, direct us to some different strategies. They are very useful lessons for me, in particular when I research my female ancestors in England, Scotland and Ireland.

At the same time, the blog reminded me how different the situation was for me in researching my female ancestors in colonial New South Wales before 1820. Three of my female ancestors arrived in those years, two free and one convict. As the procedures used to search for details about convict women have been well documented, I will focus, in this blog, on where information is available on the lives of the two women, Eleanor Irwin/Skuthorp and Jane Ezzy who were free on arrival.

Legal records

As well as the legal records which gave me so much detail about Eleanor’s court appearance, some understanding of the legal structures in early New South Wales has been important in tracing the story of Jane Ezzy. For this, secondary sources have been available to provide relevant context, and in some cases refer specifically to Jane. She is one of three free women whose ability ‘to exercise their legal agency to acquire and retain land’ has been explored in an article by Laura Donati.[2]

Jane with her convicted husband, William and their two children, arrived in October 1792 as one of the earlier free women able to accompany their husbands. Jane was promised a land grant of 30 acres near the Hawkesbury River at Mulgrave Place, now Windsor, which gave her rights to the property and produce. (I will return to the sources available for colonial land dealings in later paragraphs.)

In 1816, Jane and William, after raising seven children, ‘separated colonial style’ by inserting advertisements in the newspaper informing the public of their separation. This did not end the marriage legally but informally terminated their legal obligations within marriage. Notices were given in the Sydney Gazette in October and November 1816, the first by William, the second by Jane. William advised that he would not be responsible for any of Jane’s debts; Jane made it clear that in all her ‘dealings in trade, that [she] always received, paid, and contracted as a feme sole [single woman], and not as the wife of the aforesaid Wm. Ezzey; who has in consequence no claim upon me whatsoever, and no right whatever with any part of my business’.[3] Laura Donati’s examination of the business life of Jane Ezzy led her to state that:

Jane had made use of colonial procedures and customs, especially those pertaining to free wives of convicts under which she was treated like as [sic] a single woman, free from the disabilities imposed by coverture. Jane was fully aware of her unique legal situation and rights as a former free wife of a convict, as evident in her use of the term feme sole. This demonstrates a shrewd business acumen and a fine understanding of the nuances of the colony’s legal system and culture, both used to their fullest advantage.[4]

Leaving the Hawkesbury district, Jane Ezzy moved into Sydney Town, where she purchased two houses on Cambridge Street, which she may have operated as boarding houses or as licensed properties. The Old Registers, Volumes 1 to 9 provide details of this purchase as well as of the sale of these houses by Jane’s daughters, Elizabeth and Sophia to vintner, Thomas Thurston, in September 1823. This sale followed Jane Ezzy’s death in August 1821.[5]

Land records

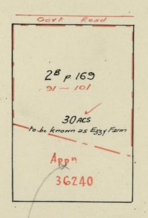

Source: J Ezzy, appl. 28670, NSW Land Registry Services

Jane Ezzy was the first woman to be granted 30 acres/12 hectares of land in the Hawkesbury district, promised in 1795, made official in May 1797. The records found through the Historical Land Records Viewer at NSW Land Registry Services for Jane Ezzy provide a sketch of the land, lease documents from the Grant Register and dates of land transactions.[6] In 1800, Jane was recorded in the Muster as having planted 9 acres/3.5 hectares of wheat, 1 acre/.4 hectares of barley and prepared another 4 acres/1.5 hectares ready for maize, as well as holding 14 pigs.[7]

Population records

The 1800 Settlers/Land and Stock Muster is just one of the population records which help locate New South Wales female ancestors. Census and Musters are also available through the subscription site, Biographical Database of Australia along with many other details about the lives of women.[8] The 1814 General Muster shows that Jane Ezzy was living in Sydney and was not being provided with stores (food). From the same Muster. I learn that Eleanor Irwin was in goal at Parramatta and described as a convict on stores.[9]

The sources I have referred to are not all that are available for researching colonial women. The value of newspapers, many of which can be accessed through the National Library’s Trove collection should not be underestimated. I have not included the numerous sources for genealogical information which form the building blocks for research on women. The history of these two women illustrates how much can be revealed about the early colonial women of New South Wales.

[1] ‘The King vs Ormsby Irwin and Eleanor Irwin his wife’, Colonial Secretary’s Papers, Reel 2752, pp. 435-7 and Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, Reel 2390, Museums of History NSW (MHNSW), https://mhnsw.au/indexes/criminal-courts/criminal-court-records-index/

[2] Laura Donati, ‘Free wives of convicts and land ownership in early colonial New South Wales’, pp. 23-42, in Journal of Colonial History, 2018.

[3] Laura Donati, p.38; Sydney Gazette, 26 October 1816, p.1 and 2 November 1816, p. 2.

[4] Laura Donati, pp. 38-9.

[5] Stephen Murphy and Jane Ezzey, Old Register, Vol. 6, p.299, entry 86, 7 July 1817; Elizabeth & Sophia Ezzey and William Thurston, Vol. 9, p. 76, entry 125, 4 September 1823, State library of Queensland.

[6] NSW Land Registry Services, https://hlrv.nswlrs.com.au/

[7] Jane Ezzy, Settlers Muster Book 1800, pp. 20-21, MHNSW, https://mhnsw.au/archive/subjects/census-and-musters/

[8] Biographical Database of Australia (BDA), https://www.bda-online.org.au/

[9] General Muster of the Inhabitants of New South Wales 1814, Reel 1252 Vol. 4/1225, MHNSW.

I’m astounded Eleanor only got two years and curious about the circumstances. But how thrilling to have ancestral connections with such early arrivals.

Christine, I think Eleanor and her husband were each spared a death sentence and convicted for just 2 years because Judge Ellis Bent knew details about Sergeant Morrow’s career as well as the circumstances of the Irwin couple and their children. Their case provides an interesting glimpse into the range of people’s experiences in colonial New South Wales.