‘An Evergreen Tree of Diabolical Knowledge’. Researching Irish in the State Library of Queensland Pt. 1.

Madam, a circulating library in a town is as an evergreen tree of diabolical knowledge! It blossoms through the year! Richard Brinsley Sheridan.

State Library of Queensland (SLQ)

Although the State Library of Queensland is a reference rather than a circulating library as recommended by Sheridan, the produce of this evergreen tree for those researching Irish people is a profusion of flowers and fruits. As part of a far-reaching forest, the available opportunities ensure that a full harvest will take many seasons as this collection covers Irish who resided in Brisbane, elsewhere in Queensland, throughout Australia, in Ireland or in other parts of the world, wherever the Irish scattering may have taken root.

Those using the State Library of Queensland at Southbank in Brisbane (or similar institutions available in each Australian capital city) learn that it comprises various branches in addition to the reference library, holding extensive resources on family history and many of its associated interests. Visitors are encouraged to use all parts of the library including its electronic facilities as well as the extensive microform centre where all microfilm and fiche sources, as well as CD Rom data disks are held on the one floor, irrespective of their provenance. Through the Public Libraries Service, support is given to a wide network all over the State.

GEOGRAPHICAL DEFINITIONS

Queensland, the last colony on the eastern coastline of Australia to receive independence, separated from New South Wales in December 1859 after being established in 1824 as a penal settlement to house Sydney recidivists for its first fifteen years.[1] The emerging district little reflected its mother colony as at the time of Separation New South Wales recently had celebrated seventy years of establishment, of which the last twenty were free of convict transportation. Moreover, Queensland’s sheer size quite dwarfed its progenitor, as it represented 22½% of the Australian continent, extending at its greatest distances, 2100 kilometres from north to south, 1450 kilometres from east to west, and contained 1,727,000 square kilometres. The wealth of Queensland lay mainly in its countryside, so the colony’s initial mission was to attract settlers to work the vast acreages by offering them the promise of purchasing their own land. During the first forty years, from 1861 until 1901 when the colonies attained statehood at Federation, settler numbers in the colony’s developing towns and pastoral districts grew to over half a million. Further, out of the 213,942 immigrants who travelled directly to Queensland, 55,218 had left Ireland. The outward thrust from places like Tipperary, Cork and Antrim to Townsville, Caboolture and Augathella continued throughout almost all the twentieth century.

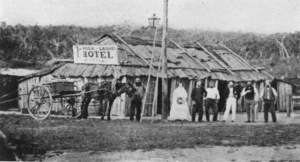

The Rock of Cashel hotel previously near Stanthorpe, part of the Photographic Collection held by State Library of Queensland (SLQ).

JOHN OXLEY LIBRARY/HERITAGE COLLECTION

The Heritage Collection, particularly the John Oxley Library, specializes in items pertaining to Queensland history. In addition to the most comprehensive collection of printed books about Queensland or by Queenslanders (as a legal deposit library), this section also contains manuscripts, business records, photographs, journals, newspapers, and private records. As well as the abundance of wisdom and products specifically directed towards genealogists, other more general sources are essential to the search. These include dictionaries, cartographic and geographic items, economic and religious tomes, occupational and demographic sources. Further, over the past thirty years, thanks to the popularity of seeking forebears, generous participants have created indexes and other finding aids with the result that biographical minutiae have multiplied almost unceasingly, and previously dense primary material has become more readily accessible. While membership of a family history society is of immeasurable benefit, whether a family is local or not, as most provide methodological lessons and specialised collections, for contextual value no one would dispute the enormous benefit of the freely accessible resources, held by the State Libraries in each state of Australia. With so many possible avenues for searching, collectable Information Guides available in the microform section, guide novices through the maze of data. Yet each place claimed as home by the peripatetic Irish developed at different times and was variously affected by changing conditions.

BASIC RECORDS AND THEIR FORMATS

As a starting point, the State Library of Queensland holds on-line, microfilm, fiche, compact discs, USBs and in printed form, indexes to births, deaths and marriages generated by civil authorities in all colonies and States.[2] Copies of certificates should be obtained from the Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages in each jurisdiction but the indexes, if used carefully and strategically, can limit expensive ‘leaps of faith’. In a few cases, full transcripts are available, among which are surviving church records in NSW (and its associated territories), 1788 to 1856, before the advent of civil registration,[3] the Anglican baptism, marriage, and some burial records for the Newcastle diocese between 1826 and 1899[4] plus Tasmanian information prior to 1896. Overall though, church records generally are retained by the specific religious organisation.

Next, monumental inscriptions and burial registers, probate information covering wills and intestacies, electoral rolls (both State since the nineteenth century and Commonwealth since 1901), local histories, military nominal rolls, education, and school listings, plus directories covering professions and occupations, all can be located here. Indexes often are available even if the original documents may be held in another repository.

ARRIVAL OF FIRST FAMILY MEMBERS

Once the basic structure of families settled in Queensland, or another State, has been established the task should then be directed towards the first Australian arrivals. Again, immigration was a state/colonial responsibility, and an extensive range of Queensland shipping lists is held in microfilm format but if an incomer remains elusive, searches always should be carried out within the collections held at other repositories, particularly at Queensland State Archives and at National Archives of Australia, both of which hold extensive ranges of complementary aspects. The State Library also can augment initial findings with a variety of books on the background of ships, for example, The Passage Makers, Michael Stammers’ story of the Black Ball clippers so identifiable with 1860s migration to Queensland, or the cumulative three volumes by Ian Nicholson, Log of Logs, a catalogue of logs, journals, shipboard diaries, letters, and all forms of voyage narratives. Further, Lloyd’s Captains’ List or calendars of ships’ arrivals in various ports are available for the asking. The John Oxley Library is home to many original handwritten ship-board diaries, particularly from the nineteenth century, which report voyage monotony, daily weather and temperatures, deaths at sea and seabird and mammal identifications. Finally, a selection of handwritten (or subsequent onshore printed) ship newspapers compiled during some of the long journeys can add even more colour. Once again, the extent of collections is not confined to Queensland borders as a comprehensive range covering other colonies can be found here enabling further possibilities to be followed through either locally or reserved for interstate or overseas visits.

St Brigid’s Day celebrations at Queensland Irish Association.

White settlement in this part of Australia was established in 1824 with many Irish among the military, civilian and convict residents. Once overseas migration to the district was encouraged after 1848, the area continued to prove attractive to Hibernians, either directly from overseas or from southern colonies, a trend which has continued to the present day. While no particularly Irish settlements were established, some areas like the Logan River, Warwick, and the Darling Downs, as well as most large towns, attracted significant numbers. Stories of districts peopled by Irish can be found in histories of Roman Catholic parishes, school records and family experiences. No part of Queensland was too distant for those who took to the bush life and no area too tropical for publicans, police, and priests. St Patrick’s or St Brigid’s Days were as big events in Brisbane city and country metropolis Charters Towers as it was in Dublin. At the State Library, read all about it and scrutinize evocative photographs.

PLANNING RESEARCH IN IRELAND

If a research trip is planned to Ireland, the bookshelves contain intriguing signposts for investigation. Valuably the Library holds a copy of Hayes’ Manuscript Sources for the History of Irish Civilisation, an eleven-volume catalogue to manuscripts, deeds and maps processed up to 1965. A three-volume supplement covering the years 1965-1975 also is held. These volumes, while noting material held by the National Library of Ireland in Dublin, further enumerate manuscripts of Irish interest in other repositories or in private custody either in Ireland or overseas. Entries are arranged by person, subject, place, and dates and then by institutions for places outside Ireland.

Other books which build a framework for precise locations like Samuel Lewis’s A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (1838), the Index to the Townlands and Towns, Parishes and Baronies of Ireland (1851), Brian Mitchell’s A Guide to Irish Parish Registers and his A New Genealogical Atlas of Ireland are ready for consultation. Those with more illustrious ancestry will appreciate A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain & Ireland (1846-9) and later editions of Burke’s. The on-line catalogue should be consulted for subjects as varied as surnames, biography, gravestone inscriptions, local histories and how to research Irish ancestry. Who would have thought that the monumental inscriptions of Copeland Island cemetery of Donaghadee in County Down would be available here in Brisbane on microfilm? Or that the parish records of New Street church in Paisley, Lanark, Scotland, or St Chad’s in Saddleworth in Greater Manchester would contain so many Irish names? In the microfiche compilation, The British Biographical Archive, 324 of the most important English language biographical reference works originally published between 1601 and 1929 have been rearranged to produce a single alphabetic cumulation. Once again Irish names abound among the adventurers, artists, astronomers, and hundreds of other professions. A most comprehensive holding of Irish publications over the past two centuries will exhaust even the most dedicated of readers.

While the prime emphasis may be placed on amassing Queensland and Australian data, the State Library of Queensland also holds a range of Irish-based products for New Zealand as well as for the United Kingdom, Ireland, Europe, Canada, and the United States. An enlightened purchasing policy extending over many years has resulted in an enviable collection. Further, demand for specialised evidence in certain years or as the result of penchants of earlier librarians has resulted in amazingly diverse offerings. Such an array offers promising results when seeking the elusive Irish.

[1] For the early history of Queensland see J.G. Steele, Brisbane Town in Convict Days 1824-1842, St Lucia, Brisbane, University of Queensland Press, 1975; W. Ross Johnston, Brisbane, the First Thirty Years, Brisbane, Boolarong Publications, 1988.

[2] The independent colonies which were created at different times during the nineteenth century were amalgamated into the Commonwealth of Australia at Federation on 1 January 1901 and from then on designated as States.

[3] This record is as complete as is possible given that all denominations did not commence in the colony at the same time resulting in many events being noted in Church of England records. Some registers or pages were inevitably lost or accidentally destroyed through the years. Further some clergy were too hard pressed to maintain records as scrupulously as present-day family historians would wish. Finally the sheer size of the country meant that part of the population was too far from churches or travelling ministers to record all incidents. The material on the films released by the NSW Register General, generally held by most libraries, ends with Volume 123 with the result that most Roman Catholic registers are not included.

[4] Until the formation of the Diocese of Brisbane in 1859, the Diocese of Newcastle included most of Queensland to an area just north of Mackay; the area beyond remained part of the Diocese of Sydney until the establishment of the Diocese of North Queensland.

Wow! So much information packed in this blog. Thank you

Di: How lovely of you to send a comment — and such a positive one too. I did enjoy writing it and only hope it proves useful to researchers. Do let me knows how you go. Thank you, Jennifer H.