Crossing Oceans

Australians, like Americans, have ancestors who came from somewhere else. My ancestors risked life and limb crossing oceans in little wooden boats, in the hope of a better future than the past they had left behind. Sailing the oceans exposed them to dangers they could hardly have foreseen – incompetent navigation, storms, icebergs, shipwreck, disease and starvation, mutiny and pirate attack – unimaginable perils that might have caused them to rethink the journey had they known how uncertain the outcome could have been.

These early voyages to the New World captured my interest because my English ancestor, George Parker, was among some 30,000 immigrants who left England in the first half of the 17th Century in search of a place to worship and raise their families without government interference. A few months before George Parker sailed on the Elizabeth & Ann, an earlier migration aboard the Angel Gabriel carrying 50 Puritans to the New World ran into a violent storm and foundered on the coast of Maine; there were few survivors.

The most harrowing account I’ve read of an ocean crossing is the History of Plymouth Plantation 1606-1646 (by William Bradford, governor of the colony for more than 20 years; William T. Davis, ed, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908; openlibrary.com). It covers the voyage of the Mayflower,which set out from Plymouth, England 6 September 1620 and arrived 65 days later, an ill-fated voyage from the beginning. The small congregation of Pilgrims who would eventually form Plymouth colony should have set off in February-March at the latest in order to arrive in the Spring, giving them time to build shelters and plant and harvest crops before the onset of winter. Departure was delayed because they had first to travel from Leiden (where they had taken refuge to avoid persecution in England) to Southampton to board the Mayflower. They chartered the Speedwell for the Channel crossing and hoped to cross the Atlantic in both ships, so that most of the congregation could be accommodated, but the Speedwell began to leak. Not everyone could board the Mayflower; there were difficult decisions about which families would stay behind.

The 102 souls who finally boarded the Mayflower endured a hellish 65-day voyage, during which one of their number accidentally drowned after falling overboard and another, John Howland by name, escaped death when the ship, knocked onto its side by strong winds and high seas, managed to catch hold of a halyard ‘and though he was many fathoms underwater, held onto the rope and with a boat hook got back onto the ship’. Living conditions on the ship were foul, cramped and primitive. A crew member, apparently resentful of the scarce rations, threatened to ‘cast half of the passengers overboard and make merry with what [was left]’, which suggests that there were inadequate provisions all the passengers (and two dogs) on board. One of the main masts had buckled and cracked, giving rise to fears that the ship could not complete the voyage. The top deck leaked onto the living quarters below decks. One violent storm after another made for a rough crossing and slow progress; Bradford estimated that the ship covered barely 2 miles per day.

Any joy they may have felt upon arrival in the New World on 11 November, 1623 was blunted by the knowledge that they had made landfall some 200 miles north of the Hudson River, the location of their land grant. The Mayflower captain attempted to steer the ship south to the Hudson but came upon dangerous shoals and turned back towards Cape Cod. A number of passengers threatened to leave the group, but John Carver (elected the first governor of the colony) framed a contract by which they agreed to ‘combine together to enact whatever laws proved necessary to preserve the group’. They all signed the contract and the noble experiment in self-government began.

Plymouth colony started off in the wrong place at the wrong time. The New England winter was bitterly cold, the landscape was bleak and inhabited by ‘wild men and wild beasts…there were no friends to welcome them, nor inns to refresh their weather-beaten bodies, no houses much less towns in which to seek succor…half-starved, many of them diseased…’ Their backs were against the sea; they could not return to England because they had contracted to repay, by the fruits of their labour, the agent who had arranged ship’s passage. They wanted desperately to get off the ship but had to remain aboard the Mayflower because it would be many months before the task of building shelters was completed by small working parties who had to wade ashore through icy water, carrying tools and rations enough to sustain them a day at a time. Barely a handful who set out from Southampton survived that first winter.

The history of Plymouth colony is part of American folklore, but the details of the voyage and the subsequent hardships of survival in an inhospitable wilderness have been blunted over time, sentimentalised into an account of a feast shared with the Indians. That first Thanksgiving was unlikely to have been a feast (although Bradford doesn’t go into much detail on the subject); more likely these devout people marked the day with prayers of thanks for their survival.

Bradford’s eloquent and honest portrayal of these events provides new insights into the founding fathers’ vision of democratic government based on the principle that, ‘At times of political crisis, the authority of the monarch [could] be suspended, but the consent of the governed could never be’.

The legacy they left to future generations: government of the people, by the people, for the people.

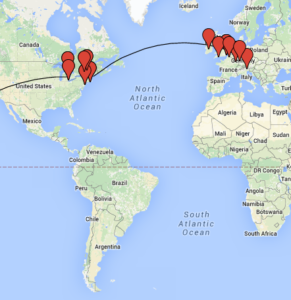

The details of my ancestors are marked on the interactive map below, accessible at

Geraldine Lee

(Additional information about the Mayflower and her passengers can be found at openlibrary.com, eg., The Mayflower and her log, Dr Axel Ames, Boston 1901).

Comments

Crossing Oceans — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>