From Convict to Landowner: The Journey of an Irishman in Australia

Sydney Cove August 1837

I spent some time researching Owen Tunny and his family when I thought he was my great-great grandfather. I now know he is not, but his son raised my grandfather, and after all my research into him and his family, I’ve grown fond of him. He was the first convict I researched, and I found myself wondering what it must have been like for him. Here’s a story of his arrival.

The Calcutta II, loaded with over 300 chained, dishevelled, gaunt and sorry men, all sent out for terms of from 7 years to life, had arrived. Owen had survived the hazardous 4-month long sea journey and now was about to get his first glimpse of the place where he would have to spend another six years, a long, long time when you are 21 years old.[1]

As he emerged from the darkness below decks, he would have noticed a sky much bluer than he was used to, and with the August sun beating down, he soon would have started to feel the heat of it through the thin layer of his clothes. Did he take a deep breath? Was that the smell of this land? Did it signal promise?

At least it would have chased away the smell of unwashed men, rotten food, rats, illness and worse. Cooped up as he had been for most of their months at sea, knowing neither night or day, except when he came up to wash in the salty water that left his skin sore and his clothes hard and stiff and then back to being cramped in the tight fit of his berth, 6 feet square to hold four convicts. He would certainly not miss that.

Painting – Sydney from the western Side attributed to George William Evans, 1803, State Library New South Wales [a1528462/XV1/1803].

Looking towards the land, he would have seen a long solid wharf, where other ships were anchored, and, on the road, carriages and carts being loaded with their cargos, both precious and mundane. Further along were buildings of honey coloured sandstone, a wide street where there were more carts, horses, and people shopping, and working. Behind the main street, the land rose up on one side, with raggedy looking houses, all higgledy piggledy. Rocks the same honey colour as the buildings rose up behind these houses and there was a stream running down the side of the hill. There were people here too, and quite a few children.

On the other side of the town, the houses were more ordered with fenced fields behind them. Scrubby trees took over at the end of the fields and covered the rest of the land that circled the bay, blue green, on all sides for miles, all the way further back to the blue-grey haze of mountains, far off.[2]

Was he frightened, angry, relieved? Perhaps he was hopeful and optimistic. After all he had already survived almost a year in prison and on board the ship.[3] Those long months at sea would have been like nothing he had ever dreamed of. At times he would have wished he had died, as many did, but he had survived.

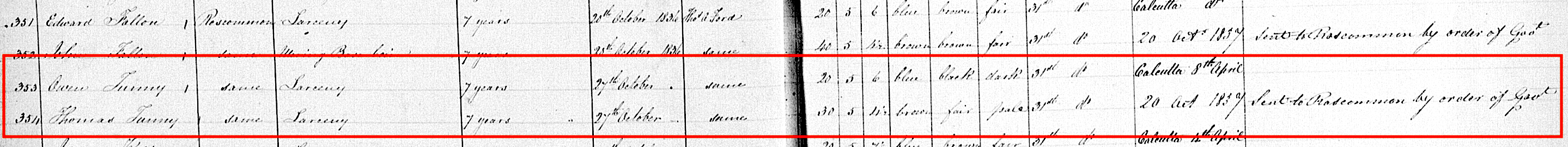

Extract from Ireland Prison Registers 1790-1924, The National Archives of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland. Findmypast.com.au accessed 1 Nov 2024.

Transportation for 7 years the judge had said at his trial in October 1836 in Roscommon Court. Thirty-year-old Thomas Tunny was convicted of the same crime on the same day. Perhaps he was a brother, or cousin? He was transferred back to Roscommon from Kilmainham Prison while Owen waited for transportation. I wonder what happened to him?[4]

What drove these two young men to risk their freedom for a bale of linen? Did they think they would get away with it? Were they criminals, or like so many others, victims of the times? Although his Convict Indent Record states he’s single, I’ll probably never know if he left behind a wife and children.[5] I do know his mother was Mary and his father John, reportedly a butcher.[6]

As soon as all the men had been offloaded, they would have marched on their unsteady land-legs into the township, past St. Phillips Church with its clock tower, past the Colonial Treasury, the Barrack Square and the town’s theatre on the left. As they made their way uptown, people would have gathered along the roadway, eager to check out the new arrivals and the custom was for many to call out as the new arrivals trudged along the street.[7]

At last Owen could get a closer look at the place and the people. He would have seen free men and poor settlers who wore cheap blue cotton jackets or short woollen blue smocks, and ‘government men’ and those on a ticket of leave, called laggers in sallow coloured jackets and pants, like those that he himself had been issued with. He would have seen the lean dishevelled children of convicts, called cornstalks or currency urchins, grown healthy by the standards of Europe on colonial corn doughboys, salt beef, fresh mutton, and vegetables. Soldiers and police were noticeable. But side by side with this martial formality, male and female sexual services were full-throatedly offered in a manner polite visitors said was more scandalous than in the East End of London.[8]

Their destination was Hyde Park Barracks, where the male prisoners were housed. They too, were built of Sydney’s honey coloured sandstone. Conditions were cramped and the work hard. He was expected to work from sunrise to sunset with an hour off in the middle of the day only if it was hot, and there were strict rules and harsh penalties for bad behaviour.[9]

Shortly later he would have found out where he was to be assigned. Perhaps he joined one of the gangs building and maintaining roads and working on the many new buildings still going up around Sydney or maintaining the Great Northern Road between Sydney and Windsor, in the Hawkesbury region where he eventually settled. A jail entrance record in 1840 records his transfer from Maitland ‘to other stations’.[10]

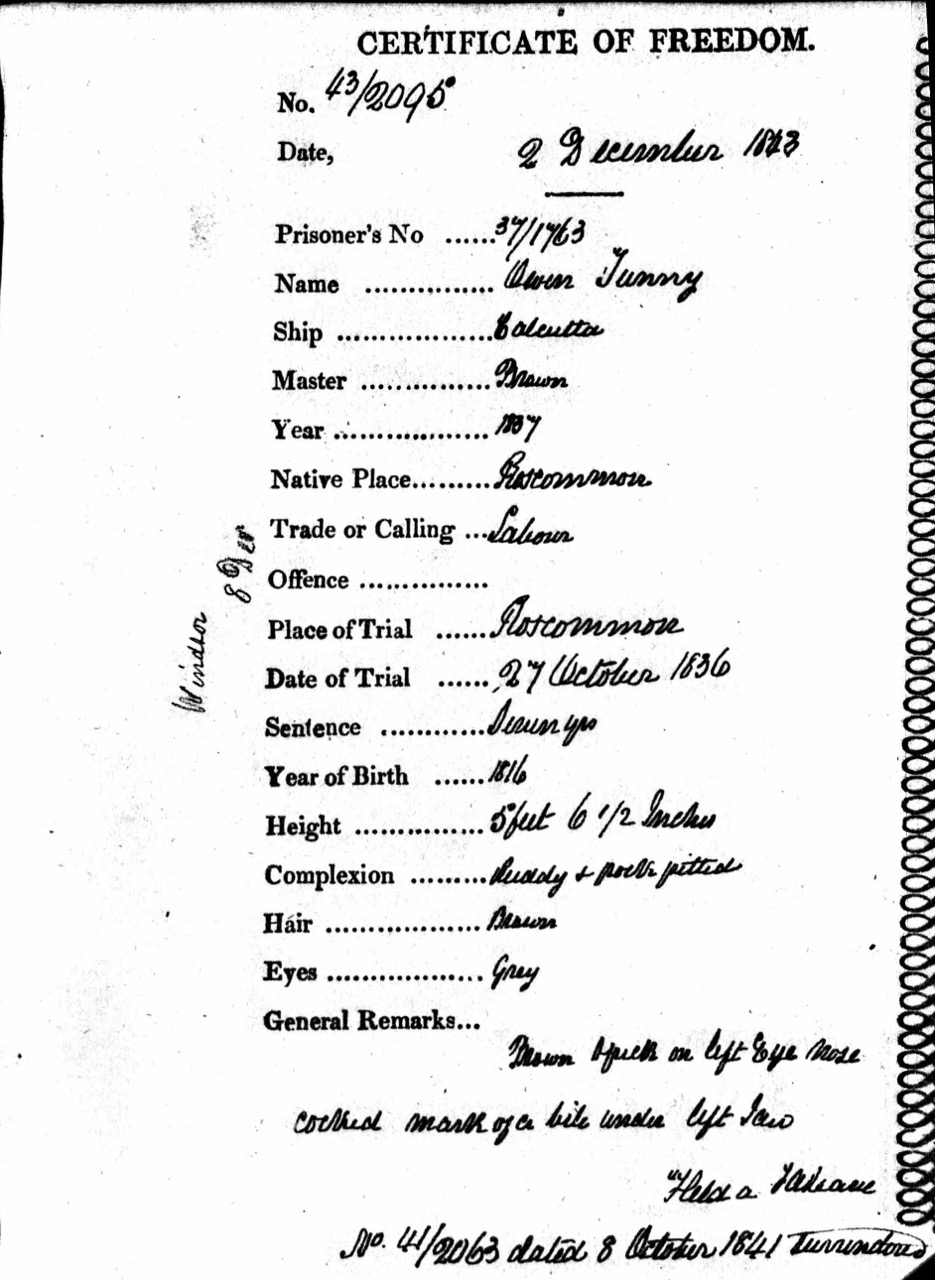

Certificate of Freedom for Owen Tunny, 2 December 1843.

He moved to the Windsor district some time during his sentence, and it seems he was able to keep out of trouble as on 8th October 1841 he was granted a Ticket of Leave to remain in the Windsor District. Two years later, he officially became a completely free man when he was granted his Certificate of Freedom.[11]

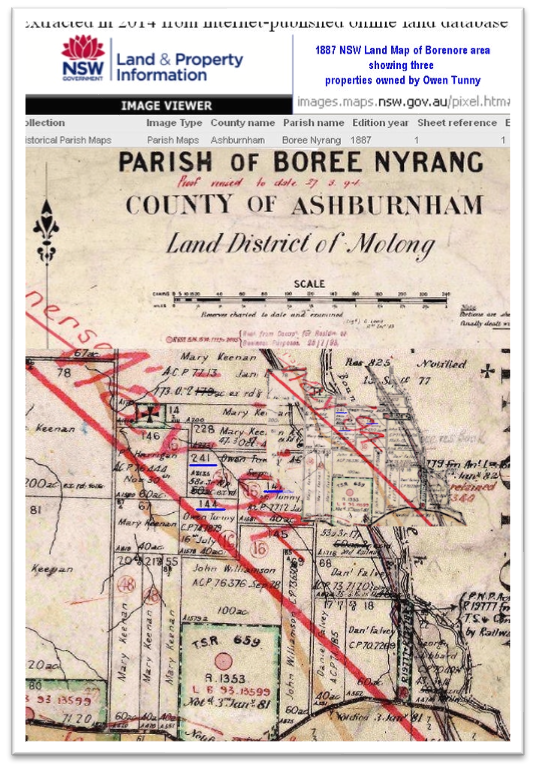

New South Wales Land map of Borenore area showing three blocks of land, portions 241, 147 and 144, owned by Owen Tunny in 1887. New South Wales Land and Property map, Orange District, Ashburnham County, Boree Nyrang Parish. Extracted 2014.

In 1846, he married Mary Ann Harrison, herself the daughter of two convicts. They set up home on Wheeny Creek, Colo, where he worked as a boatman. They later moved to Borenore, near Orange where he became a landowner and farmer, something he probably would not have been able to achieve in Ireland.[12] He never returned to Ireland and although he seems to have had a hard life, he and Mary Ann had thirteen children and began a legacy of family that continues on today through his children, grandchildren and so on. Owen passed away at 87 years-of-age in 1898.[13]

[1] Ireland Prison Registers 1790-1924, The National Archives of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland. Ancestry.com, 2020, Lehi, UT, USA. Owen was 20 here, but 21 by the time he arrived in Australia.

[2] Keneally, Thomas, 1935-. (2010). Australians. Volume 1, Origins to Eureka (chapter 14) Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, N.S.W.

[3] After his trial in Roscommon in October 1836, Owen was transferred to Kilmainham Prison at Dublin to spend the six months that passed before setting out for Australia on 19 April 1837.

[4] Ireland Prison Registers 1790-1924, The National Archives of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland. Ancestry.com, 2020, Lehi, UT, USA

[5] New South Wales Convict Indents 1788-1842, ancestry.com

[6] Registration of Owen Tunny’s Death Certificate reg 6682 NSW

[7] Keneally, Thomas, 1935-. (2010). Australians. Volume 1, Origins to Eureka (chapter 14) Allen & Unwin , Crows Nest, N.S.W.

[8] Keneally, Thomas, 1935-. (2010). Australians. Volume 1, Origins to Eureka (chapter 14) Allen & Unwin , Crows Nest, N.S.W.

[9] Museum of History New South Wales. www.mhnsw.au/

[10] New South Wales Australia, Gaol Description and Entrance Books, 1818-1930, State Archives New South Wales, Roll 136. www.ancestry.com

[11] New South Wales Australia, Certificates of Freedom 1827-1867. Certificate for Owen Tunny, 2 December 1843

[12] New South Wales Land map of Borenore area showing three blocks of land, portions 241, 147 and 144, owned by Owen Tunny in 1887. New South Wales Land and Property map, Orange District, Ashburnham County, Boree Nyrang Parish. Extracted 2014. Current online map of portions 241 and 147 are shown in name of Clara S. Ivers (Owen’s daughter). Portion 144 shown in name of F.A. Williamson (probably Frederick Albert Williamson, Owen’s nephew).

[13] Australian Death Index, 1787-1985. Owen Tunny 1898, New South Wales. Certified copy Death Registration, photocopied from book held at Windsor library, The Tunny Family, by Mrs G.M. Valais, call number RL20994TUN.

Yvonne, it’s great how you describe those first impressions and life in Sydney in the 1830s. Really puts Owen Tunney’s life in context.

Christine

Thanks Christine,

I wrote this story quite a few years ago. I wanted it to read more like a story. I’m pleased that you appreciate it. Revisiting it has inspired me to redo some of my other work.

My great great grandfather, one Patrick Monaghan was an Irish convict from County Galway who at the age of 19, during the Potato Famine was convicted of stealing a pig and transported to Australia on the HAVERING.

He arrived in Moreton Bay and was assigned to Joshua Bell to work his Ticket of Leave on Jimbour Station.

How fortunate I feel he was to have been assigned to the Bell family.

He met his wife Catherine Nelligan, an Irish lass who came to Australia as a free settler, a domestic employed by the Bell family at Jimbour.

Patrick lived for many years at Jimbour working as a station hand before making good and purchasing land at Kaimkillenbun. During his time at Jimbour my great grandfather William Monaghan was born and married one Jane Mackie a Scottish lass whose parents William and Maryann Mackie also worked on Jimbour Station. William later become head stockman at Jimbour.

My grandmother Catherine, William’s daughter, was also born, schooled and worked on Jimbour Station.

As a result I feel a deep connection to Jimbour Station and the Bell family who were instrumental in setting the foundation for my early ancestors and thus my existence.

Hi Leonie,

Thanks for sharing about your great great grandfather and his journey. I think Australia provided such a unique opportunity for a great many of these early men and women to prosper and become landowners themselves. Something they probably would not have done had they stayed in Ireland.