Missionary Encounters at Moreton Bay.

This is an amended extract of my story previously published in the Genealogical Society of Victoria’s magazine, ‘Ancestor’ in June 2022 and recently in the June 2025 edition of the Genealogical Society of Queensland’s ‘Generation’ magazine. Part one of the larger story also appeared in my blog in June 2025.

The Brisbane penal settlement on Turrbal land, which began in 1825 as a place for the most hardened and second time offenders, was closing down in 1838. Fewer than 300 convicts remained when my second great-grandparents arrived after a traumatic sea voyage.[1]

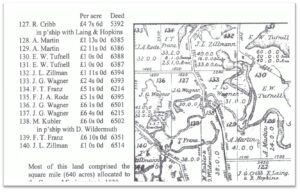

Land at Nundah, from A. J. Egan, Nundah Mission to Suburb, edited and produced by Mavis Baxter, Noela-Gibson-Wilde and Bruce Gibson-Wilde, Nundah and Districts Historical Society, Qld (2010), page 26.

They were members of a group sponsored by Rev. John Dunmore Lang, the first Presbyterian minister of Sydney, to establish a mission to the Indigenous people in Moreton Bay.[2] One of the group’s leaders, Pastor Eipper, wrote to Reverend Lang about the mission’s location and their intentions. They had chosen a spot about seven miles from the government station (in Brisbane City) and had called their mission Zion Hill. It later became German Station and is now the Brisbane suburb of Nundah.

It seems there was already some suspicion that the indigenous people were not entirely happy with the intrusion:

…To go farther away from the settlement at present is impracticable and would be folly indeed for though two or three tribes in the immediate neighbourhood are friendly and inoffensive, it is only fear of our fire-arms which has made them so…[3]

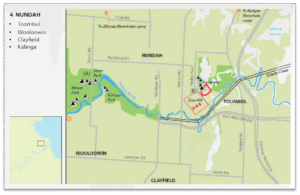

Nundah was a busy thoroughfare to various Moreton Bay regions—north, south, east, and west. The area where the mission was located—now the suburb of Nundah—had two large camps, one of which was quite close to the mission site.[4]

Main Indigenous Camps of Nundah from Dr Ray Kerkhove, Aboriginal Campsites of Greater Brisbane…An Historical Guide…(Brisbane, Boolarong Press, 2015). Page 53.

Early interactions with the Turrbal people seemed favourable, with some locals attending Sunday services — if the missionaries were willing to share food and tobacco.[5] Too often the missionaries did not have enough food for themselves.[6]

By 1840, differences in lifestyle and values had begun to generate conflict. Both sides appeared to believe they were entitled to the Nundah crops, which the Aboriginal residents had helped farm on land they still considered to be their own. The missionaries were obliged to dispense with their bell; a tin dish beaten by a stick, used to summon them for evening service, as it provided an ideal opportunity for the Indigenous people to avail themselves of some of the missionaries possessions. On one occasion, some missionaries fired guns to scare them off, leading to an inquiry from the Moreton Bay commandant and an explanation sent to Lang.[7] After this, the camp residents repeatedly raided and destroyed crops at every opportunity. Yet children continued to attend the Mission school and many residents from the camps worked with and for the missionaries as “good washerwomen, farmhands and regular water-carriers.”[8]

In late 1840 and early 1841, conditions for the missionaries worsened as Moreton Bay district was subjected to severe flooding, resulting in a lack of supplies. The Commandant, Lieutenant Gorman, wrote to Governor Gipps on 18 February 1841:

…The very scanty supplies that have been received by them from their society in Sydney has left them in a state bordering on starvation during the last months. I have been obliged to issue them with 1,050lbs of flour from the commissariat magazines here: they have not received any supplies by the last vessel. One of the females fell into such a state of extreme debility, induced by want of proper nourishment after her confinement that the medical officer deemed it necessary to remove her to hospital…[9]

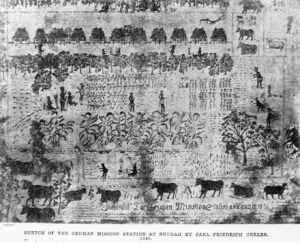

Gerler, C. F. (n.d.). Sketch of the German Mission Station at Nundah, Brisbane, 1846.

The woman referred to was my second great grandmother, not long after the birth of her second child. She was admitted on 30 December 1840 and not discharged until the end of April 1841.[10]

By 1842, seventeen children had been born at the mission. The missionaries erected a schoolhouse and chapel—it was the first school for Indigenous children.[11]

After 1842 the mission was administered by a committee of various denominations in Sydney, but when the New South Wales government withdrew funding in 1843, their support also ceased and the mission was left to its own resources, independent of any church group. Also in 1843, a government survey was completed. The five year grant on the 640 acres of Zion Hill lapsed, and the area was declared open to free settlers, who ‘took up’ the Aboriginal land. The indigenous people retreated, making contact more difficult for the missionaries. Some missionaries left with Rev. Eipper moving to Sydney in 1844.

With increasing pressure for land from new settlers, the Governor decided the mission was too close to the Brisbane settlement and that it must transfer further north where the aboriginal tribes were to be found. They recommenced working an outstation at Nordga—now Burpengary—twenty-six miles north, which they had earlier abandoned after several altercations with the Indigenous people there. But in 1845 an attack on the life of missionary Gottfried Haussmann, which nearly succeeded, led them to give it up entirely.[12]

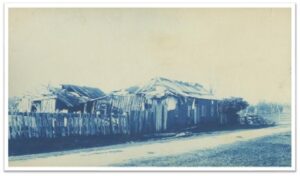

Picture of last building at Zion Hill; Commons contributors, “Zion Hill last building 1895.jpg,” Wikimedia commons.

After the mission was abandoned, the remaining missionaries chose to keep working and farming the land at Zion’s Hill (now German Station). New settlers resented their presence and success, noting that although the missionaries made few religious converts, they prospered as farmers and graziers, with their produce valued in Brisbane and their cattle herds thriving.

… Our readers are perhaps aware that the German Mission is also abandoned. Sir George Gipps, we think wisely, finding its utter uselessness has discontinued the assistance that it formerly received from the public revenue. The German missionaries, phlegmatic and philosophical, have become German graziers and market gardeners. Located on the rich land of Eagle Farm, commanding an extensive back run; paying neither licence or assessment, it may be gratifying to their friends at a distance to know that they are ‘doing well’; that is, that they have much cattle, and their butter and vegetables are highly prized in Brisbane, that if their spiritual harvest has been small, their vegetables are most luxuriant, and if during their mission, they have made no converts, their last increase in calves is at least ninety percent.[13]

The mission continued until about 1850, when it was finally abandoned. Some of the original missionaries purchased land in the area they had worked for years. Johann Zillman and my second great grandfather, Theodore Franz, also purchased land in the Caboolture district. According to a local source, they were the first settlers at Stoney Creek (now Burpengary Creek).

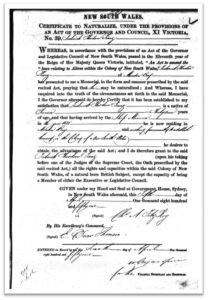

Naturalisation Certificate for Friedrich Theodor Franz “Certificate of Naturalisation” 1849-1903, State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia.

More than 150 years later, much has been written about the failure of the mission.[14] The reasons were complex. A lack of funding and the effort to become self-sustaining undoubtedly reduced their capacity for missionary work. Their European cultural biases prevented them from recognising that the Turrbal people already had a sophisticated spirituality grounded in connection to the land.

The essentially well-meaning missionary goals of Christianity and humanitarianism were in opposition to —and ultimately overruled by—economic interests and colonial expansion. Mission activity in Nundah and early Queensland in general, was incompatible with the forces of colonial growth. Yet the names of these men continue to appear in the later history of Nundah and southeast Queensland. Nundah’s camps saw some of the earliest European studies of Indigenous culture and language and were also a conduit through which Indigenous people first encountered European culture, technology, beliefs and foods.[15]

In 1851, my second great grandfather, Theodore Franz, obtained his certificate of naturalisation as an Australian citizen.[16]

[1] Museums of History of New South Wales, “Moreton Bay Penal Settlement”, (https://mhnsw.au/guides/moreton-bay-penal-settlement/(accessed 21 May 2025).

[2] D.W.A Baker, Lang, John Dunmore (1799-1868), “Australian Dictionary of Biography”, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lang-john-dunmore-2326 Published first in hard copy 1967 by Melbourne University Press, (accessed online 27 July 2025).

[3] “Original Correspondence”, The Colonist, Sydney, NSW: 1835-1840;12 May 1838; ; accessed online 27 July 2025.

[4] Dr Ray Kerkhove, Aboriginal Campsites of Greater Brisbane…An Historical Guide…(Brisbane, Boolarong Press, 2015).

[5] Ganter, Regina (2014), Digging in: German Humanitarians in early Queensland, Queensland Review (21), 2, pp122-141.

[6] Harris, John, (1990) One Blood: 200 Years of Aboriginal Encounter with Christians: A Story of Hope. Albatross Books, NSW, page 110.

[7] Griffith University Queensland “German Missionaries in Australia, Zion Hill Mission”,http://missionaries.griffith.edu.au/qld-mission/zion-hill-mission-1838-1848.

[8] Dr Ray Kerkhove, (2015) page 558.

[9] Egan, A. J. (2010) page 13.

[10] Colonial Hospital Records, Hos. 1/1/7, 23-25. Records of cases treated Brisbane General Hospital, 1841-50, cited in Egan A. J. page 17

[11] Dr Ray Kerkhove, (2015) page 56.

[12] Egan, A. J.(2010) page 17.

[13] “Aboriginal Missions” Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane Qld, 1846 – 1861) Saturday 27 June 1846, p2.https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3715767?searchTerm=aboriginal%20missions%20June%201846

[14] Johnston, A. (1997), “God being, not in the bush”: The Nundah Mission (Qld) and Colonialism. Queensland Review, 4(1), 71-80.

[15] Dr Ray Kerkhove, (2015) page 57.

[16] New South Wales “Certificate of Naturalisation” 1849-1903, State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia.

I would love to get in contact with Yvonne Tunny. I am from the Friends of Nundah Historic Cemetery and next year we are celebrating 180 years since the first burial. We are wanting to publish a book 180 Stories 180 Years we are asking for family, historians, anyone who would like to submit a story to do so. As Yvonne has strong ties with the cemetery we would love to chat.

Thanks Michelle, I’ll be in touch. I believe my mother was a member of your group many years ago.