The Fever Ship Minerva

Mum was moving into a retirement unit, and we sat on her bed as she tipped out a box of old photos and cuttings. I picked up some yellowed pages, stapled together in the corner. I flipped through the pages until I came to a longer entry for “FRANZ, Frederick Leopold Theodore”. I read how he was part of a missionary group who arrived in Australia in 1838 where they founded a mission in Moreton Bay at what is now the Brisbane suburb of Nundah.

I was intrigued. Here was a young man who had left his home and country to travel thousands of miles to become a missionary. There were twelve men and eight women in the group. Most were young and in their twenties. They had left their homes and country to travel thousands of miles to set up their mission. What had motivated them? Was it their beliefs, or the chance of a better life? I imagine it was a bit of both.[1]

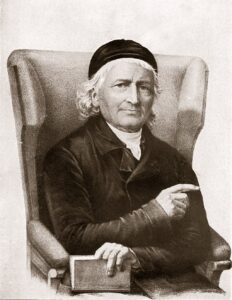

“Johannes_Evangelista_Gossner_1773-1858.jpg,” Wikipedia.

Those pages started me on a journey and passion that would last many years. The journey for my second great-grandparents was not so enjoyable.

The mission was organised by Reverend John Dunmore Lang, a pioneer Presbyterian minister of Sydney. Reverend Lang had made unsuccessful attempts to recruit volunteers from his native Scotland, but the Scottish clergy he was able to attract preferred to work in the established areas of New South Wales, rather than the frontier of Moreton Bay.[2]

My second great-grandfather, Theodore Franz and five other young men seemed keen to train as missionaries. After being turned away by the admission rules of other mission societies, they approached Pastor Johannes Evangelista Gossner of the Bethlehem Church in Berlin, and he took them on as his first students.

Johannes Gossner had been a Catholic priest whose approach to the scriptures brought him into conflict with the Catholic Church and he converted to Protestantism. He was a founding member of the Berlin Mission Society, but again his views differed from the mainstream and put him at odds with the rest of the Society, so he resigned to found his own; The Gossner Mission. He believed that the ‘Godly mechanic’ made a better missionary to primitive peoples than highly trained scholars. Rather than a prolonged education for missionary candidates, he thought that missionaries should be self-sufficient and support themselves by working with their own hands.[3]

He is quoted as saying “I promise you nothing; you must go in faith,” he told them “And if you cannot go in faith, you better not go at all!” While attending Gossner’s school, the students were expected to support themselves by their own trades. Theodore was a tailor. Among the rest was a stonemason, a carpenter, a blacksmith, a weaver, a shoemaker, a butcher, a gardener and a bookbinder.

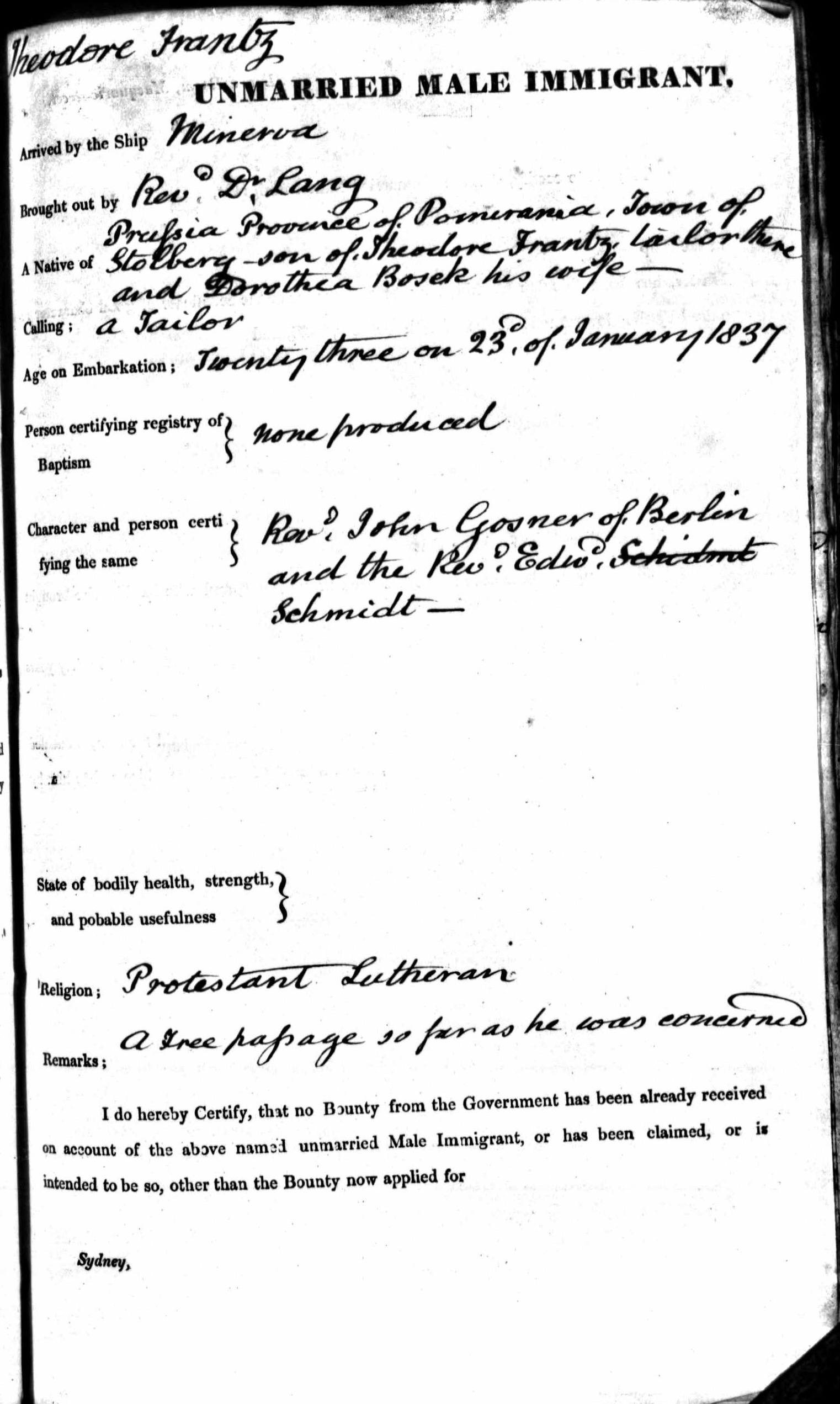

Immigration record for Minerva, Theodore Fran(t)z: “New South Wales, Australia, Assisted Immigration Passenger Lists, 1828-1896,” database, Ancestry, (Accessed 25 May 2025)

In early 1837, Reverend Lang called seeking volunteers for his Christian mission. Theodore and the rest volunteered, keen to be godly mechanics and to test the dream of their mentor.

Two ordained ministers lead the group. Reverend Wilhelm Schmidt was a pastor in Berlin and one of Gossner’s students. The other minister, Reverend Christopher Eipper, had been ordained by the Evangelical clergy in London.

Two of the mission group were already married and just before the mission group left Berlin in July 1837, Pastor Gossner married six of the others. My second great-grandmother, Dorothea Weiss, was one of these. But in July 1837, she married Moritz Schneider, a medical student from Leipzig, Saxony. Theodore and three others remained single.

They set out the next day, first to Britain where they were joined by Pastor Christopher Eipper and his wife. The students then received their final training with the Presbyterian Church authorities before travelling to Greenock, Scotland where they boarded The Minerva in September 1837.

The Journey[4]

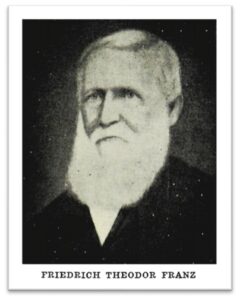

Freidrich Theodor Franz, from N.W. Gunson, “The Nundah Missionaries, Queensland Journal of History, 6(3), 1960, 519-539″.

Two hundred and thirty-five people embarked on the voyage. The other passengers were mostly Protestant, mostly Scottish and some Irish, tradesmen, women and children, also sponsored by Reverend Lang.

The journey started well. A diary of the day-to-day events by one of the passengers notes that they enjoyed music and dancing soon after departure. Perhaps they thought of the sunshine and land promised, rather than the three long cramped months at sea or that they may never see their home or loved ones again, or the illnesses and death that could befall them. Sadly for some, this would be all too true.

Those who suffered seasickness recovered rapidly. With favourable winds, the passengers were in good spirits and enjoyed many new sights. Despite their sparse English, the missionaries kept busy with a christening, a marriage and a funeral during the first three weeks.

By November the mood on board changed. Many steerage passengers were now unwell with typhus, and among them was the doctor’s sister. The missionaries were now kept busy with funerals as the deceased were quickly buried at sea. When the ship’s doctor became ill, the missionaries took on the care of the sick, led by Moritz Schneider. Some of them, including Theodore and Moritz succumbed to the fever. He recovered on January 16, but Moritz was ill when they landed.

When she arrived on 23 January 1838, The Minerva was directed to the Spring Cove quarantine station but could not land as the hospital only had 18 beds and there were nearly 40 sick people. They were finally allowed to land over a week later.[5]

It was a heart rendering sight we are told, to witness the condition to which a brief illness has reduced the sufferers; the greater part being unable to leave their beds were lowered down the side in hammocks.[6]

Eighty-six passengers had been affected by Typhus and 14 had died. Thirty-four remained ill. The settlement took the quarantine seriously. Soldiers were posted to ensure that none left and that no townsfolk came in.

North Head Sydney, Photograph of The Hospital, Boiler House and Wharf at Quarantine Station. Wikipedia.

(Accessed 25 May 2025)

There were disputes. Newspaper reports printed letters from those trapped at the quarantine ground complaining of the lack of supplies. On one occasion, they had trouble getting soap and a request for spirits and wine was seen as completely unnecessary.

The missionary Moritz Schneider died on 3 February. He was buried in the Quarantine church cemetery. The missionaries conducted a service and carved his name and birthplace on a stone. They had lost a valuable worker even before their task of converting the aborigines began. And yet, were it not for his death, our family would not exist as it does today for Theodore Franz later married Dorothea Schneider née Weiss and they had six children, from one of whom our family is descended.

Some of the missionary group were released from quarantine in February and left for Moreton Bay in March. Pastor Schmidt and my second great-grandparents were not released from quarantine for several months. They finally left for Moreton Bay in June.

Overall, about 28 people died either on the voyage out or in quarantine.

I had mixed feelings when I discovered my ties to such a venture. I felt some pride that my ancestors were amongst the first free settlers in what would later be Queensland, but I was uneasy about how they may have interacted with the indigenous people and what was it like to live at the mission?

My next post will look at what happened when the missionaries arrived in Brisbane.

[1] Egan, Allan Joseph (Joe) Nundah: Mission to Suburb, (Edited and produced by Noela Gibson-Wilde and Bruce Gibson-Wilde, Nundah Historical Society. 2010)

[2] Ganter. R., Digging In, German Humanitarians in early Queensland, Queensland Review, volume 21, issue 2, p122-141, p123.

[3] N.W. Gunson, “The Nundah Missionaries,”Queensland Journal of History, 6(3), 1960, 519-539.

[4] Henderson, W, “An account of a passage from Greenock to Sydney, New South Wales, in the ship Minerva,” https://www.freesettlerorfelon.com/minerva_fever_ship.html (Accessed 19 December 2020.) Egan, Allan Joseph (Joe) 2010. Champion, B.A (Lib. Sc.) and George Champion, Dip. Ed. Admin “The Ship Minerva in quarantine 1838,” (1993) Killarney Heights, New South Wales, Online thesis, https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=6dedc9f5bcd1f3d5cfbbf92e8919cf6cccf2eaf7.

[5] The Ship Minerva in Quarantine, 1838, thesis by Champion, Shelagh, B.A. (Lib. Sc.) and Champion George (George Annells), Dip. Ed. Admin, https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu.

[6] The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, “The Fever Ship Minerva,” Tuesday 6 February 1838, p 2.

Note: Yvonne previously related the above story in ‘Ancestor’ magazine, Volume 36 Issue 2 in June 2022 published by the Genealogical Society of Victoria.

Comments

The Fever Ship Minerva — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>