The Ground Beneath Their Feet: Discovering Family Stories through Land Records.

Family history often begins with names, dates, and events of birth, marriage, and death, captured within certificates, registers, and electoral rolls. Yet sometimes the most revealing records are not about people at all, but about land. The soil our ancestors walked upon, purchased, and cleared, land long cared for by its Traditional Custodians, holds traces of their lives in ways that vital records never can. Through land records we can locate where they lived, see how their circumstances changed, and understand the world they helped to shape.

As family historians, we work with records created within the framework of colonial settlement. It’s important to remember that the lands our ancestors received, farmed, or purchased were already home to Indigenous peoples who had cared for Country for thousands of years. Every land record carries both a family story and a deeper, older one.

Blending landscape and archive, this image represents how land records unite history, place, and memory. An AI generated image.

Why Land Records Matter

Land is more than a physical possession. It represents belonging, effort, and aspiration. For those who left few written records, it may be the only surviving footprint of their existence.

Land records help us:

- pinpoint where an ancestor actually lived and worked;

- trace migration or settlement patterns;

- reveal networks of neighbours, kin, and community;

- identify economic or social status through ownership or tenancy;

- fill gaps where civil or church records are missing; and

- connect a family’s story to the broader patterns of local and colonial history.

Unlike many other sources, land records offer continuity. Families may appear and disappear from electoral rolls or parish registers, but their transactions, the purchase, lease, or inheritance of property, can be followed across generations.

What makes land records unique is that they follow the property rather than the person. While most genealogical sources attach information to an individual, land records attach it to a parcel of ground. As families acquire or relinquish land, the records form a chain that links one occupant to the next. By tracing that chain, we uncover not just ownership but movement, change, and community over time.

Reading Between the Lines: What Land Records Can Reveal

Beyond the question of “where did they live?”, land records can answer many others that help flesh out a life story. They can:

- Determine ownership – who held the title, when it was acquired, and what it cost;

- Assess wealth at death – comparing property value in probate or rate records;

- Show succession – revealing who inherited or purchased the land after your ancestor;

- Identify acquisition – discovering who your family bought the land from;

- Provide context – illustrating social standing, occupation, and community ties;

- Offer visual insight – maps and plans provide an immediate sense of landscape and scale; and

- Encourage curiosity – because each discovery leads to “many other reasons” to explore further.

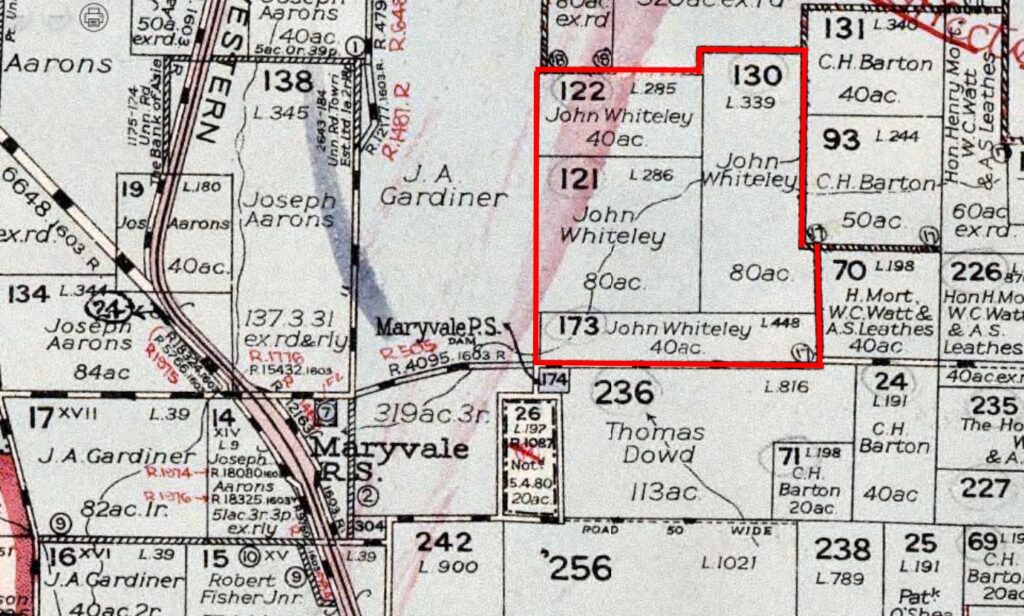

A snippet of 1933 map of Parish Micketymulga, County of Lincoln near Wellington, NSW with John Whiteley land portions outlined in red. Accessed NSW Historical Lands Record Viewer, 15 Mar 2024.

A Map Full of Stories

When I first examined this parish map, I outlined my third great-grandfather’s (John Whiteley) property in red. What became immediately clear was that the family holding was not a single parcel but several adjoining portions. Research revealed that from an initial purchase he was later able to secure more land as his family grew. Whether this reflected prosperity, determination, or a mix of both, it showed a man steadily building a future through the land beneath his feet.

That same land remains in family hands today, having passed through different branches over the generations. Part of it is now being converted into a solar farm, a modern use that feels both surprising and inevitable. Time continues to move on, yet the landscape still carries the marks of those earlier choices.

As I studied the map more closely, familiar names began to appear. Several daughters of nearby landholders married sons of the Whiteley family, their connections mirrored in the grid of adjoining blocks. The inclusion of Maryvale Public School, now closed, led me to search the school admission registers and find generations of family members listed as pupils.

A single map, I realised, could open up many directions for research. It revealed the ties of family and friendship, the growth of a community, and the continuing relationship between people and place. Every allotment and annotation told a story of those who once lived, worked and learned within its boundaries.

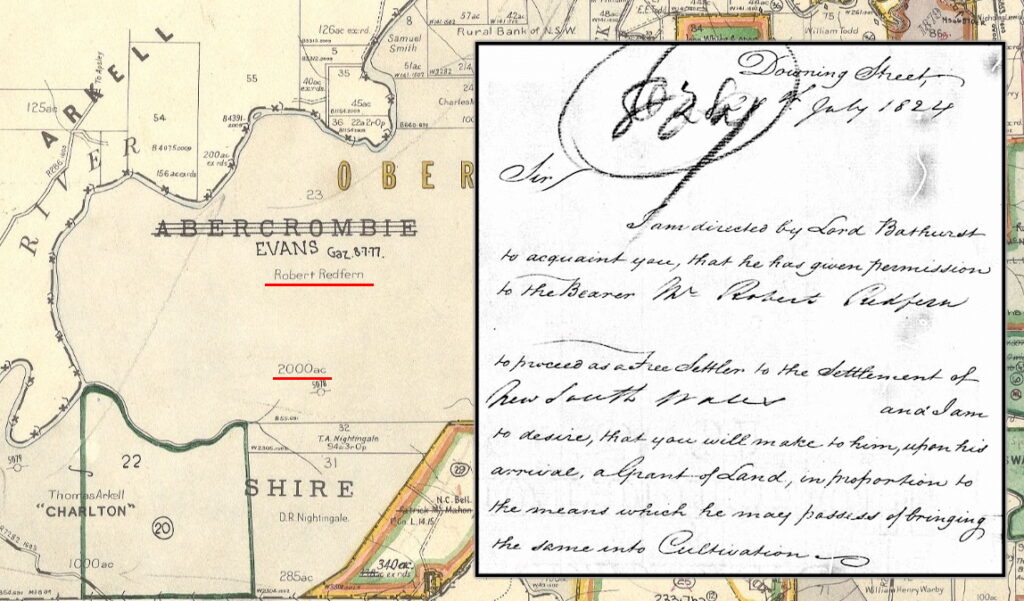

The resulting land grant (map) received by Robert Redfern in 1825 as a result of the letter (inset) from the Colonial Secretary in 1824. Map from NSW HLRV, letter from AJCP.

A Letter from London and a Grant in Westmoreland

Among the most revealing discoveries in my research was a letter sent from Downing Street in July 1824, granting my third great-grandfather, Robert Redfern, permission to proceed as a free settler to New South Wales. The letter instructed the colonial government to allocate him land “in proportion to the means which he may possess of bringing the same into cultivation.”

Following that thread led me to the original land grant in the County of Westmoreland – the fulfilment of that promise. It transformed an abstract bureaucratic instruction into a tangible place on the map: real soil that he cleared, fenced, and farmed. The grant marks the beginning of his life in the colony and the foundation from which later generations would build.

Records like these take us, as researchers, from a London directive to a colonial plan, revealing not only the mechanics of settlement but the personal stakes within it: courage, ambition, and hope for a new start.

A deeper explanation of the investigation into Robert Redfern’s land grant can be found at: https://andrewredfern.com/unlocking-robert-redferns-land-grant/

The Birth of a Suburb

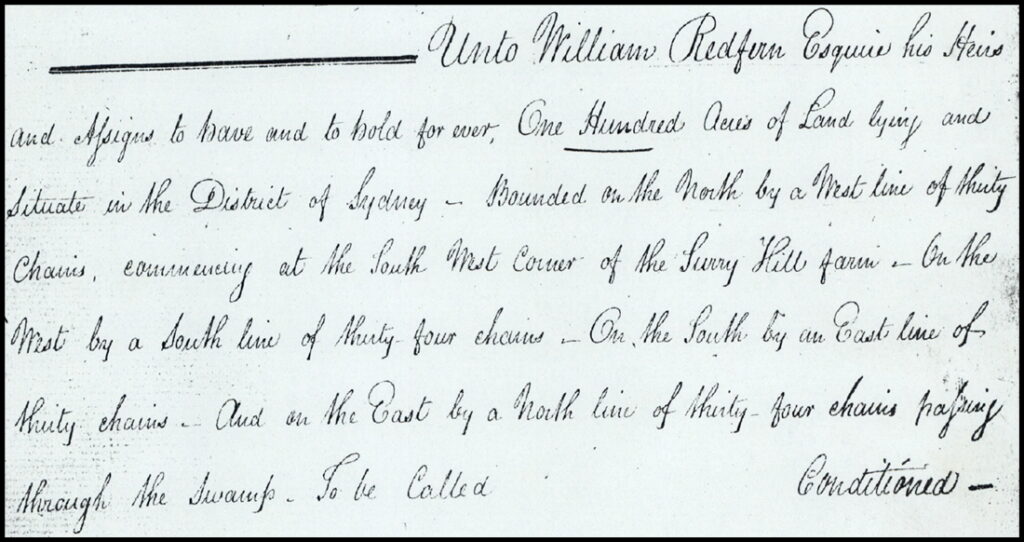

Sometimes land records lead far beyond the family fence line. In tracing the history of my Redfern ancestors, I followed documents back to the original grant that gave rise to the Sydney suburb which still bears their name.

To stand in Redfern today, surrounded by streets and terraces, and know that the name began with a single parcel of 100 acres of granted land, is to see how individual lives ripple outward through history. What begins as one man’s grant becomes a community, a suburb, a city story.

Part of the original land grant to William Redfern which subsequently became the suburb of Redfern in Sydney, NSW Historical Lands Record Viewer, Grants Index, retrieved 11 March 2011.

The Land Beneath My Feet

Not all discoveries lie in the distant past. Curiosity led me to trace the history of the property where I grew up. By following titles, rate books, and historical plans, I could see the line of previous owners, each chapter marking change and continuity. It was humbling to realise that our family’s years upon the farm we called, “Wongajong” had in fact being Edge Hill and Woorooboomi previously, reinforcing my family as being just one small part of a longer narrative written into that land.

Piecing Together Place and Story

To bring these records to life, combine them with other resources. Overlay parish maps with modern satellite images to see where old boundaries still lie. Compare names on adjoining properties with your own family to uncover new connections. And if possible, visit the site itself, to stand where your ancestors once stood and imagine the view they saw. And don’t be surprised if you have a sense of your ancestors being there with you. It is as if the landscape itself remembers. Land records are a bridge between archival research and lived experience. They transform abstract data into geography and emotion.

An AI imagined Australian landscape representing the enduring connection between family, land, and memory.

Standing Where They Stood

In the end, land records remind us that history is not just about people but about place. The soil our ancestors walked, fenced, and cultivated is part of their story, and ours. When we trace those boundaries and locate those forgotten huts or long-sold parcels, we find more than legal transactions. We find evidence of endurance, ambition, and belonging.

Family history, after all, is not only about who our ancestors were, but where they stood.

Disclaimer: This article was developed with the assistance of artificial intelligence. The ideas, structure, and content were conceived and directed by the author.

An excellent article Andrew., both the content and structure. Also a fine example of how best to integrate and acknowledge the use of AI. Thank you!

Thanks Rosie. So pleased you found it useful and being transparent with the use of AI is a key principle of engaging with the technology.

This is a wonderful story and all you’ve found is incredible! Well done. You have given us encouragement to pursue where my ancestors bought stood and farmed Queensland land! Thank you!

Thanks Cheryl. Land records are a great resource but can be a little tedious in tracking them down. But the payoff is well worth it. Start small and focus on one piece of land at a time is my advice and record everything. Even numbers you don’t know what they mean because you will need them one day.

Love your blog, Andrew. Land records are important, and Shauna Hicks is doing an education session on Qld land records in the second half of next year. Thanks for the blog.

Marg Doherty

Thanks Marg and I do love land records. Look forward to the education session by Shauna in 2026.

Andrew, your blog encourages me to dig much deeper. Also your acknowledgement of A1 usage is a wonderful example.