The Hallams’ Pioneer Days in the Whitsundays

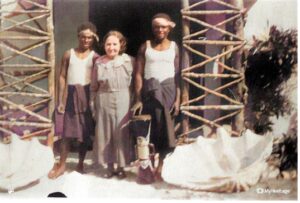

Mary Sheehy with Torres Strait Islanders on Hayman – 1930s. From author’s family album, colourised at MyHeritage.

I’m planning to write a longer story about the Hallam family and their pioneering life in the Whitsundays. This blog shares some starting thoughts.

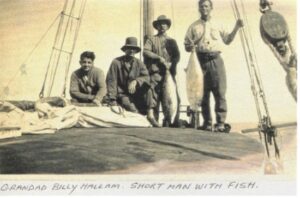

My great-grandparents, William (Billy) Hallam and Mary Josephine Sheehy, raised nine children, all born in Bowen, North Queensland. What strikes me about Billy, a man of short and nuggety build, is how industrious he was, taking all kinds of work depending on the season. It was a pattern that repeated itself in the next generation.

When Billy met his bride-to-be sometime between mid-1884 and 1887, he was a jackaroo on Inkerman station, at the back of Ayr and Home Hill. Their first child, Susannah Elizabeth was born Bowen in April 1888, which might explain why Mary, an Irish Catholic immigrant, took her vows in Bowen’s Trinity Church of England in March 1888 when she wed Billy Hallam.

Mary was tiny, with thick black hair, deep-set dark eyes and a slightly pointed nose and chin. I wouldn’t describe my great-grandmother as beautiful, but her dark eyes spoke of intelligence, and her features belied a mischievous sense of humour. Mary was a domestic servant at Salisbury Plains station, north of Bowen, when she and Billy met at a country dance.

Billy Hallam third from the left. From author’s family album.

As a seaport of growing importance from the mid-nineteenth century, Bowen’s economy depended upon fishing, timber and the pastoral industry. With a child on the way, Billy and Mary decided their future lay on the coast where, provided you were quick to learn and prepared to do anything, you stood a better chance of determining your own future. Considering the promise of work, the Hallams started married life by setting up house on Dalrymple Street near Bowen’s wharf.

For a man with no previous experience of the sea, Billy adapted quickly by crewing on boats and coastal ships. He laboured at the wharf and fished until he had saved enough money to buy a small boat. Owning his own boat meant Billy could travel out to the islands to cut timber, such as Hoop Pine, in response to the never-ending demand to develop Bowen, Proserpine and Mackay. Because of the plentiful supply of such a valuable resource, the Whitsunday Islands were initially called the Pine Islands.

The Scottish immigrant, John Withnall, landed in Bowen in 1883 just after a cyclone had wreaked havoc through the settlement. A carpenter by trade, he soon found plenty of work. By 1888, with his wife Jeannie, John established a timber mill on Whitsunday Island, in Cid Harbour. The newly formed Queensland State Government encouraged settlement on the islands by offering leases to pastoralists and homesteaders. John was granted a ten-year lease encompassing five acres in Cid Harbour in November 1895 (Blackwood: 1997, p. 224).

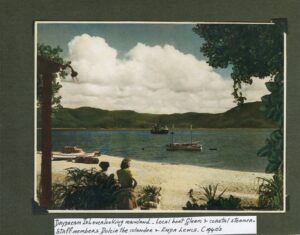

Daydream Island overlooking the mainland. From author’s family album.

Aboriginal people still camped and moved about the islands at this time, with evidence of early Aboriginal connection, if not permanent habitation, including old fireplaces, shell middens, stone fish traps, and tool fragments on many islands. The largest permanent tribe still lived on Whitsunday Island in the early twentieth century.

Fatal attacks between European mariners and indigenous tribes frequently occurred, indicating that the Whitsunday tribes fiercely resisted colonial intrusion. As time went on, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders worked for leaseholders on various islands. When Captain James Adderton took up a grazing lease on Lindeman Island in 1905, Billy Moogerah, with fellow clansmen from the Whitsunday Ngaro tribe, constructed stone dams across some of the island’s waterways to secure fresh water catchments (Daniels: 1990).

Six Hallam children were born in the Dalrymple Street Queenslander before it was blown off its stumps during Cyclone Leonta in the early hours of 9 March 1903. Holding onto the children, one being two years old, Billy and Mary waded through a rushing creek to shelter in Bowen’s railway station, which had opened in 1890. The only item salvaged was a mantle clock that was blown out of the house as the walls were smashed into splinters. The clock landed on the beach where it was found half-buried in sand. It still enjoys pride of place in a Hallam home.

Sugar plantations, built on the backs of indentured South Sea Islanders, were a thriving industry from the 1860s. Once a mill was constructed beside the Proserpine River in 1897, a settlement to house its workers soon sprang up around it.

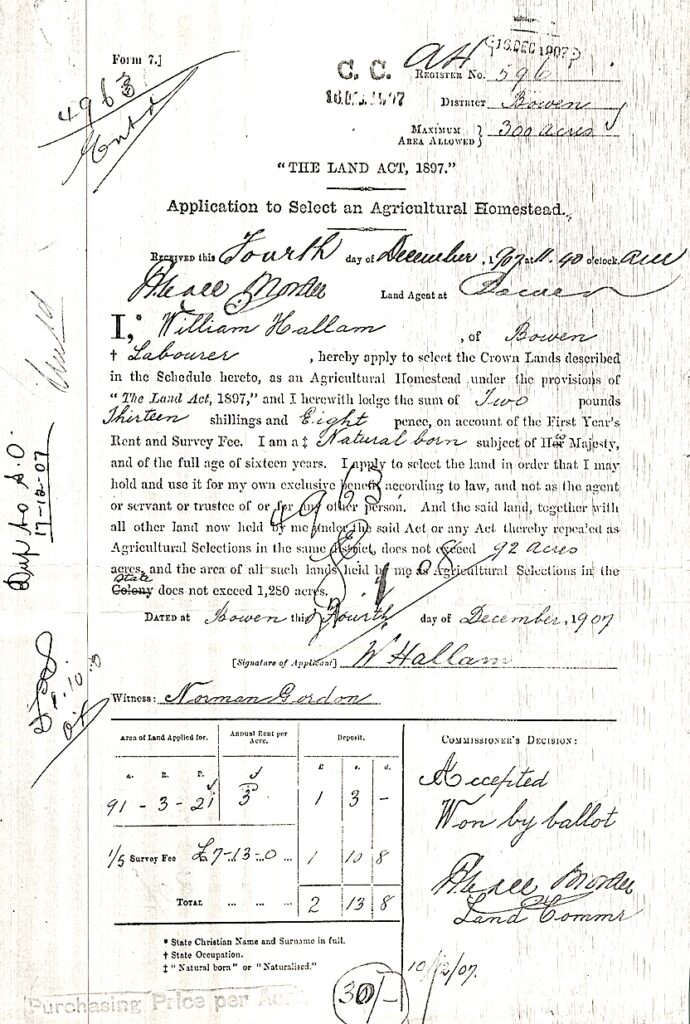

Page 1 of William’s land title. From author’s collection

In December 1907, Billy won a ballot of ninety-two acres of uncleared scrub and forest in Riordanvale, near Cannon Valley on Pioneer Bay. The property was close to the now famous Airlie Beach and about 13 miles to Proserpine. Eager to start their new adventure, the Hallams headed south in a horse and dray. Initially, Billy cleared five acres to plant sugarcane, resulting in his first harvest being crushed at the Proserpine mill in 1909. Cane was cut by hand, loaded onto a cart drawn by horses and taken to a tramway siding. The tramline leading to the mill wasn’t far from the farm. By 1913 when the deed of grant was paid out, it included a four-bedroom house on seven-foot posts, valued at £130. When it wasn’t harvest time, Billy worked on his boat, Stella, fishing and timber getting. He also transported passengers to and from the islands.

The Hallams family home in Cannon Valley about 1930s. From author’s collection.

Cyclones are a part of Queensland life, and disasters are never far away. One of my grandfather Bob Hallam’s, earliest memories of cyclones was 23 March 1911. At thirteen, he was fishing with his father in the Whitsunday Passage. The wind was getting up. It looked like a cyclone was coming, so they headed out of the Passage towards Shute Harbour to ride out the storm. In the distance, just on dark, Billy and his son spotted the lights of a vessel passing Long Island before disappearing into the mist.

‘What do you make of it, Robert?’ Billy yelled as the wind and rain howled in the dark.

Despite the boat’s violent rocking and the boy and his father being drenched to the skin, they were mesmerised by the lights blinking on a seesawing horizon. They would hear later that the lighthouse keeper on Dent Island had also seen lights at the northern end of Whitsunday Passage at 6.35 pm that same evening.

On that day, the SS Yongala, a 3,604-ton steel screw steamer, one of the largest ships in the coastal trade, was steaming north from Brisbane to Cairns, with over 120 people (The Brisbane Courier, 1911, Trove). The ship never reached its destination. It would be forty-seven years before the wreck of the SS Yongala was discovered off Cape Bowling Green. My grandfather believes that he and his father were the last people to see the ship before it sank.

Family home of Robert (Bob) Hallam and his family in Dalrymple Street, Bowen. From family album.

Despite Billy and Mary’s boys growing up to start their own ventures, the Hallam brothers always came together at harvest time to cut the cane on their parents’ farm. My grandfather followed in his father’s footsteps for several years, timber-getting and fishing. In the early 1920s, Reg Hallam, the third youngest, took over the farm, keeping it in the family until the 1940s. Billy and Mary moved to Proserpine by the mid-1920s for the next chapter in their lives.

References

Blackwood, R. ‘The Whitsunday Islands An Historical Dictionary’, 1997. Central University Press, Rockhampton, Queensland.

Winsor, Valda Busuttin. ‘Island That We Knew’, 1982. Bruwal Ltd Hong Kong.

Daniels, T. 1990. ‘The Days Back When’, The Daily Mercury, 23 Aug 1990 Mackay.

Article: Three Days Overdue, The Brisbane Courier, 27 March 1911, p. 7, viewed 28 Oct 2025. Available online at http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article19667626

Christine,

I really enjoyed this story and how lucky are you to have a family album going back that far.I think it would have been a pretty good time for those nine children, hard work but still lazy days as well.

Many thanks,

Hi Gayle

thanks for your comments. Yes I feel very lucky to have the photos. And being black and white many are in pretty good condition. They wouldn’t have lasted if in colour. They did have a wonderful childhood, and having that sense of freedom and independence from a young age helped them grow up very resilient, which I think applies to many of that earlier generation. Life was tough but as children unless they went hungry, they didn’t look at the hardships in the same eyes as their parents. What I love about family history is getting to know the characters and personalities

Very interesting life they had and mostly they were there at crucial times when the places were just developing and having aboriginals still there would have been great. I love the photos too. Worthwhile having this history.

Thank you Ros. Re the photo of Mary Sheehy, I believe she is standing with Torres Strait Islanders. There was a lot of movement around the Barrier Reef with the pearling and beche de mer trade.

The period during WWII will bear out some interesting events especially in the lead up to the Battle of the Coral Sea.