A fascinating family history diversion – finding Cicely Beven

It all started with allowing myself to be deflected off course. I had been looking for a possible reference in Trove to an aunt who had done some pottery in the 1930s and had been associated with L. J. Harvey and the Harvey School. I was not successful in finding a mention of her, but I noticed the names of many Queensland artists listed, some of whose works we had collected over the years. On a whim I searched for the name C. Beven which was the signature on two much loved watercolours of St John’s Cathedral purchased from an antique shop about thirty years ago. Previous searches of the internet and Australian Art sites had failed to reveal any information about the artist. Through the newspapers of the day, however, a fascinating story unfolded.

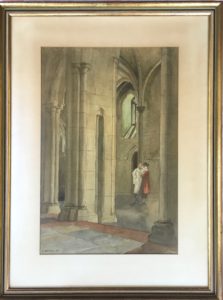

St John’s Cathedral, Brisbane. Painting by Cicely Beven, owned by Lyn Irvine

Cicely Beven was born in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1913. She came to Brisbane with her parents in the late 1920s and the family lived at Ellerslie Crescent, Toowong. Her father, Harry, had been a police magistrate at Matara in Ceylon and was from a well-known and respected family. Her mother, Constance Davey, was the daughter of the Hon A.A. Davey, a boot manufacturer and foundation member of the Queensland Commercial Travellers’ Association. He was also a member of the Queensland Legislative Council during the term of the Kidston Government, remaining there until 1922 when the Upper House was abolished.[1] Cicely attended Taringa State School and later All Hallows. After leaving school, she went on to study art at the Brisbane Central Technical College.

During her time at the Technical College, Cicely won acclaim for her art. In November 1934 a review of the college’s annual art exhibition in the Telegraph noted:

Miss Beven with pen and watercolour is happy in her presentation of that picturesque landmark, Old St. Stephen’s Cathedral, an interior view of St John’s Cathedral, a landscape and drawings from life.[2]

In December of the same year, reviewing the same display, D. R. McConnel wrote:

Cicely Beven has a fine solemn interior of an aisle in St John’s Cathedral.[3]

St John’s Cathedral, Brisbane. Second painting by Cicely Beven, owned by Lyn Irvine

In 1936, at the age of 22 and in the fifth year of her studies, Cicely was accepted into the famous University College London Slade School of Fine Art, on samples of her work.[4] She acknowledged that there were many better students than herself at the Technical College who could not afford to go, but that she was fortunate in being able to travel and continue her studies independently. Her plan was to concentrate on developing her talent as a line draughtsman with a view to doing figure work.[5]

Sailing on the Orontes from Sydney on the 23 February 1936, Cicely reached London where she attended the Slade for a time and then moved to St. Martin’s School of Art where she studied under Leon Underwood.[6] Leon mainly taught wood engraving, with an emphasis on life drawing. Henry Moore was one of his most famous students.[7]

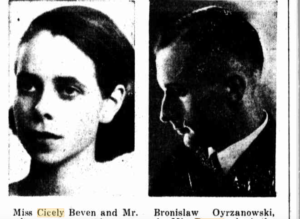

It was whilst Cicely was studying in London that she met and fell in love with a Polish man by the name of Bronislaw Oyrzanowski. Their engagement was announced in the Brisbane papers at the end of May 1937 and they were married on 10 June at St Pancras Town Hall. As neither the bride nor groom had relatives in London, the wedding was a very quiet one, after which they left for two weeks honeymoon in Guernsey, returning to London for Bronislaw to finish his studies in Economics.[8]

Cicely Beven and Mr Bronislaw Oyrzanowski Engagement photo. The Telegraph (Bne) 25 May 1937 p14 ‘Artist Engaged’

The couple left London for Warsaw, Poland, at the beginning of August 1937, and went to Bronislaw’s family home at Kutno, 60 miles from Warsaw where they lived until the start of 1939 when Bronislaw took up an appointment at Cracow.[9] Life in Warsaw was very interesting for Cicely, who apart from learning the language herself and negotiating housekeeping in a foreign country, was also occupied giving lessons in English to a number of very keen students, including one of Warsaw’s principal heart specialists, and another academic who was a highly qualified engineer.[10] During this time also, Cicely wrote articles for the Brisbane Telegraph about her life in Poland. Her artist’s eye was in evidence as she charmingly described the manners and customs of the peasant folk of Lowicz 50 miles west of Warsaw, painting a word picture of the colourful hand woven skirts of the women and children. The vertical stripes of red, orange, black and vivid pink of these stiff full skirts stood out against the great white-washed and green-garlanded interior of the “ugly red brick church” where they were attending mass. They were “so brilliant that they seemed unsubstantial – like light shattered in a piece of glass, or a spray of water”.[11]

But this was 1939 and there were dark clouds on the horizon. On the 1st September, in the early hours of the morning, some 1.5 million German troops invaded Poland all along its 1,750-mile border with German-controlled territory. Simultaneously, the German Luftwaffe bombed Polish airfields, and German warships and U-boats attacked Polish naval forces in the Baltic Sea.[12] At that moment in time, Cicely and Bronislaw were spending a summer holiday at Gdynia, a lovely seaside town and port which was invaded and blockaded by the Germans.[13] Letters home prior to invasion had shown that while like the rest of Poland Cicely was fully alive to the gravity of the situation, she felt no trace of fear, and although Bronislaw had wanted her to return to Australia out of harm’s way, she elected to stay and do what she could to assist the Polish people.[14]

Following the German invasion, Cicely’s family in Brisbane had no further contact and did not know whether she had been killed or taken prisoner. The Foreign Office reported that Madame Oyrzanowski had not been heard of and that it had no means of making enquiries in Poland. The Polish committee inquiring into war victims was endeavouring to ascertain whether she had been made a prisoner by the Nazis.[15] However there was no news.

The Universities of Poland were a particular target of the Germans. Their aim was a complete annihilation of Polish intellectual life. The University of Cracow where Bronislaw taught, was an important centre and was singled out for destruction. One hundred and seventy academics were summoned to University Hall, and addressed by the chief of Gestapo in German. He declared that since they had tried to reopen the University without authority and were arranging examinations of undergraduates without German permission, all professors in the hall would be arrested. They were deported to concentration camps where they were cruelly treated and many died.[16]

It was not until March 1940 that a postcard written by Bronislaw in Cracow and forwarded through the International Red Cross reached Cicely’s mother in Brisbane stating that they had been in Cracow when it was bombed but had escaped injury. His parents had also survived. There was no further contact until May 1942, when again there was word through the Red Cross Missing Friend’s Section, this time written in French by Bronislaw’s mother, that they were well and working.[17]Information dried up again until July 1943, when a letter arrived typewritten by the International Red Cross but signed by Cicely, saying that her husband was working in an office, and she was “as usual” which her mother understood to be teaching English, as that was her previous occupation.[18]

Wonderful as it was to receive these infrequent messages, anxiety did not abate concerning Cicely and her husband in war ravaged Poland. Over two more years passed before any further word was heard, even for a considerable time after the war ended. The family feared the worst. Then came news that they were indeed still alive but that during the German occupation both Bronislaw and Cicely had suffered greatly. She had been arrested by the Gestapo and imprisoned for twelve months. Bronislaw was also imprisoned for many months for helping prisoners who had escaped a concentration camp.[19] But there was good news as well for Cicely’s mother. Early in 1945 Cicely and Bronislaw had become the parents of a baby girl.[20] Out of darkness, hope.

By March 1947, things were starting to return to some degree of normality. Cicely wrote that jobs were plentiful in Poland. She herself was translating from Polish into English a book by a blood specialist. She was also teaching languages to adults at the YMCA and, under the auspices of that same association, had started a kindergarten for children aged from three and a half to six years, all of whom were learning English. Her husband Bronislaw had become assistant Professor of Economics at Cracow University.[21] By the second half of 1948, Cicely’s mother had been able to visit the family and acquaint herself with her new granddaughter, Elzbieta, a visit which she repeated in 1949, staying with the family for six months and enjoying Polish cuisine and the resurgent live theatre, including seeing “Much Ado About Nothing” performed in Polish![22]

Bronislaw Oyrzanowski died on November 11 1997 in Cracow. He had a distinguished international career in Economics, including working for the United Nations in Addis Ababa and Dakar. He was made professor of Economic Sciences at the University of Cracow in 1976, and after his retirement from there in 1983, went on to lecture at the University of Wisconsin. He was very widely published. Cicely died in 2000. She had continued teaching English for many years and had co-authored a book entitled I learn English.There is no record of her having continued with her art, but I would like to think that in quiet times and for her own pleasure, she did so. Those paintings of St John’s Cathedral that I have always loved are now made more precious by the revelation of the fascinating life story of the artist, a story that like the art itself, will be passed on down the line as part of my own family history.

[1] Death of Mr A.A. Davey, Former M.L.C. Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Saturday 28 June 1941, page 15[1] Death of Mr A.A. Davey, Former M.L.C. Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Saturday 28 June 1941, page 15

[2] Students’ Art Efforts, Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld: 1872-1947) Wednesday 28 November 1934, page 17

[3] “YOUNG ART in BRISBANE” The Courier-Mail (Brisbane, Qld. : 1933 – 1954) 14 December 1934: 16. Web. 17 May 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article35627533

[4] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Saturday 8 February 1936, page 1

[5] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Saturday 8 February 1936, page 19

[6] “THE SOCIAL ROUND” The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947) 3 November 1936: 18 (SECOND EDITION). Web. 1 May 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news

[7] Leon Underwood https://www.redfern-gallery.com/artists/61-leon-underwood/overview/

[8] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Tuesday 6 July 1937, page 1

[9] Daily Mercury (Mackay, Qld. : 1906 – 1954), Thursday 16 November 1939, page 10

[10] “From VERITY’S NOTEBOOK” The Courier-Mail (Brisbane, Qld. : 1933 – 1954) 10 March 1938: 1 (Second Section.). Web. 4 May 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article39753642

[11] Polish Peasants Retain Traditions. Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Monday 28 February 1938, page 13

[12] Germans invade Poland https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/germans-invade-poland

[13] “Brisbane Woman In Poland” The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947) 2 September 1939: 10 (SECOND EDITION). Web. 1 May 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article191593657>

[14] Brisbane Woman Missing in Poland. Daily Mercury (Mackay, Qld. : 1906 – 1954), Thursday 16 November 1939, page 10

[15] Missing Brisbane Woman Stood by Polish Husband. Courier-Mail (Brisbane, Qld. : 1933 – 1954), Wednesday 15 November 1939, page 3

[16] Gestapo in Poland. Seats of Learning Closed. From a Polish Correspondent Friday March 1 1940 Library Times Newspapers Limited London, England

[17] Daughter Safe in Poland. Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Friday 22 May 1942, page 6

[18] “BRISBANE GIRL IN POLAND” The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947) 16 July 1943: 4 (CITY FINAL LAST MINUTE NEWS). Web. 1 May 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article186323472>

[19] Bronislaw Oyrzanowski Encyklopdia Zarzadzania https//mfiles.pl/pl/index.php/Bronislaw_Oyrzanowski

[20] “BRISBANE WOMAN SAFE IN POLAND” The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947) 2 January 1946: 4 (CITY FINAL LAST MINUTE NEWS). Web. 1 May 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article188438527>

[21] Brisbane Woman in Poland. Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Tuesday 4 March 1947, page 4

[22] “Much Ado” In Polish” Brisbane Telegraph (Qld. : 1948 – 1954) 17 December 1949: 7 (LAST RACE). Web. 5 May 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article216430315>

What a fascinating discovery! And the connection with St John’s Cathedral is very special.

How lovely to read this fascinating story, and to learn of Cicely Beven’s connection to St John’s Cathedral where I am a parishioner.

Cecily Beven is my second cousin (once removed)

Fascinating account of her life. Thank you.

I am a Dutch Burgher, born in Ceylon. migrated and is living in New Zealand.