Deviations: should they be avoided?

Shoe Cottage dated 1666 at Blunham, Bedfordshire.Photo by author.

I am often guilty of deviating from my family history research! I start out on solving a problem and suddenly I’m devoting hours to researching something not directly related to my ancestors. Should I try to be better disciplined?

Recently I was on the trail of my Lovell family and quickly found myself researching the life of John Lovell who was totally unrelated to my ancestors, although I didn’t realize it at first. I became increasingly enthralled with his story as I explored further. Let me explain.

I was researching John Lovell who was my 3x great grandfather. He was born at Blunham in Bedfordshire in 1785 and was a shoemaker.[1] The deviation commenced when I discovered a newspaper report for a John Lovell in December, 1839. When I read that this John Lovell was involved in a riot, was captured, convicted of high treason, and sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered, I was hooked! My immediate concern was that this was my John Lovell, and I was curious about his dire circumstances. And so, the hunt for more information was on!

As this John Lovell was born in 1798/99, I can safely assume that he was unlikely to be my ancestor. According to the many newspaper reports, he was a gardener and became involved in an uprising at Newport in Wales in 1839.[2] I needed to investigate what the riot was about.

In the early 19th century, the existing political system favoured the wealthy and powerful of society, with both the House of Lords and the House of Commons consisting of nobility and church leaders, as well as wealthy landowners. The Members of the House of Commons were elected by a privileged few as only 1:12 men were assessed as being eligible to vote. In 1832, with the passing of the New Reform Bill, that ratio became 1:6. There remained widespread dissatisfaction with these results. The Corn Laws of 1815, introduced to benefit the wealthy, resulted in widespread financial hardship and poverty. This served to exacerbate the desire for change to a fairer electoral system.

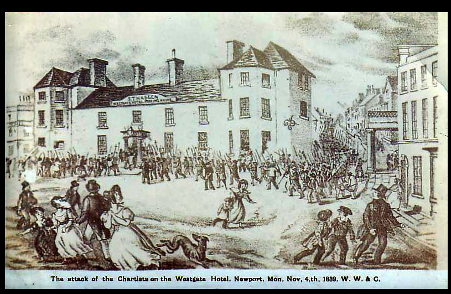

Attack of Chartists at Newport 1839. Wikipedia public domain.

In 1838, a group of ‘radicals’ under the direction of William Lovett, the son of a master mariner in Cornwall, devised a “People’s Charter”, demanding vital democratic reforms to the political system. They included:

- A vote for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for a crime.

- The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote.

- No property qualification for Members of Parliament to allow the constituencies to return the man of their choice.

- Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen, working men or other persons of modest means to live or interrupt their livelihood to attend to the interests of the nation.

- Equal constituencies, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors, instead of allowing less populous constituencies to have as much or more weight than larger ones.

- Annual Parliamentary elections, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation since no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal manhood suffrage in each twelve-month period.[3]

When the existing parliament rejected the Charter, the Chartist movement introduced strategies to increase support. Articles promoting the ideals of the Chartist movement were published through a newspaper known as “The Northern Star”. Those who were unable to read, could assemble in a public venue and listen as the newspaper articles were read aloud, increasing support for the Chartist movement.[4]

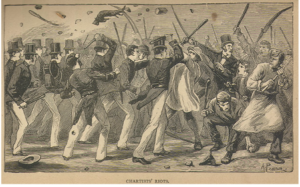

Chartists Riots. Wikipedia public domain.

Meanwhile, as the movement gained momentum, John Lovell became a leader. On November 4, 1839, thousands of men from many parts of Wales joined forces and armed with rudimentary weapons, rebelled against the imprisonment of the Chartist leader Henry Vincent and the rejection of the People’s Charter. They were attacked by military foot soldiers from the 45th Regiment, killing at least 22 Chartist supporters and wounding more than fity. John Lovell sustained a serious gunshot wound to his thigh. He was one of 14 men who were committed for trial at Monmouth Special assizes on November 09, charged with high treason and sedition. They were found guilty and sentenced to the heinous punishment of being ‘hanged, drawn and quartered’ (this was the last time this sentence was imposed in the UK). Following widespread protest, the sentence was commuted to transportation for life.[5] For John Lovell, this sentence was commuted to 5 years imprisonment at Millbank prison. His wife, Rebecca lodged four petitions, with 119 signatures for his release from Millbank. He was released on 10 August 1844 and seven years later, John and Rebecca were living at Brook House in Newport, Wales, where John resumed his work as a gardener.[6]

This has been a fascinating diversion for many reasons. I have wondered whether any of my ancestors were supporters of the Chartist movement. I have gained some insight into the economic and political climate during this period of history, and I have a better understanding of how our democracy evolved. This research most definitely has not been a waste of my time! For now, however, it’s back to my real Lovell family research.

[1] Baptism of John Lovell, England and Wales, Non-Conformist Births, Baptisms, Blunham Bedfordshire, Parish Baptisms, Findmypast.com.au.

[2] Findmypast.com, “The Newport Riots”, Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, 14 Dec. 1839.

[3] “Remembering Chartist leaders found guilty of high treason in Newport Rising of 1839”. Teifidancer: Random thoughts in a digital age. Saturday, 16 January 2021, https://teifidancer-teifidancer.blogspot.com/search?q=16th+January.

[4] Chartist Ancestors, “Northern Star- the paper that made Chartism”, https://www.chartistancestors.co.

[5] “Remembering Chartist Leaders found guilty of high treason in Newport Rising of 1839”.

[6] Census record for John Lovell, aged 52, Brook House, Penhow, Newport Monmouthshire, 1851 England and Wales census, The National Archives, HO107/2451/15, UK Cen sus collection, Findmypast.com.

Very interesting. It’s great to go down a rabbit hole, isn’t it?

Thanks Di, ever since I realised that understanding the context of my ancestors lives was vitally important to their story, my interest in family history became a passion! Deviating is essential and so much fun!

I’m a great fan of rabbit holes or chasing BSO’s if one can spare the time. They give us opportunities to be educated, entertained and enthused – and isn’t that what genealogy is all about.

From Beverley Murray:

Most definitely Jill. Again, my interest in family history becomes a passion when I research local history, social history, political history, etc. etc. Forgive my ignorance, but what is a BSO please?

Hi Bev, BSO are Bright Shiny Objects ie anything that deviates your main object of researching.