“The Singing Flame”: Destruction of public records.

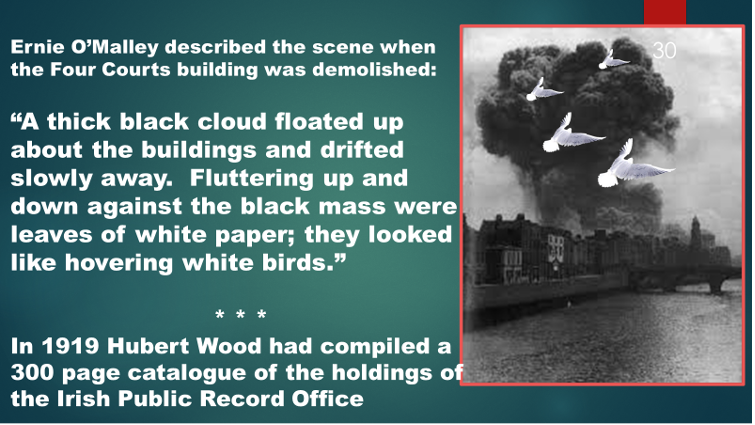

One hundred years ago, on 30 June 1922, the Four Courts building in Dublin was bombed and thousands of government records were destroyed in the blast. Ever since, historians have rued the extensive devastation of valuable source material which the current Irish project Beyond 2020 seeks to remedy. Ernie O’Malley in his book, The Singing Flame, described the carnage: ‘Flame sang and conducted its own orchestra simultaneously’. Staunch Republican O’Malley who reported directly to Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy during the War of Independence and could not accept the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty with Britain on 6 December 1921, was a perfect witness being in the Four Courts when the Free State army attacked. After capture and imprisonment limited his prospects locally, he moved to the United States where, to critical acclaim, he wrote his memoirs.

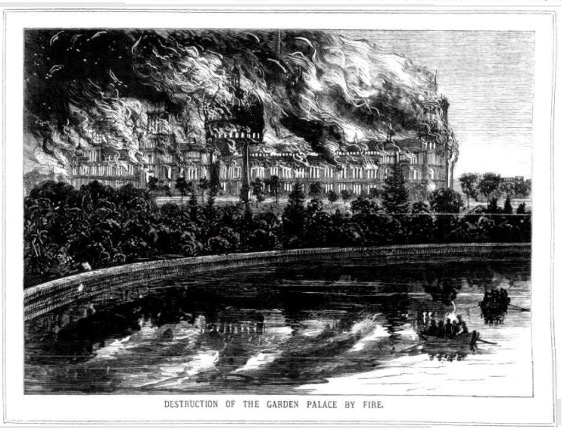

This disaster was not the first, nor indeed the last time that precious documentation has been lost in a repository disaster. In New South Wales, forty years before the Dublin blast, on the morning of 22 September 1882, the Garden Palace in Sydney’s centre was totally razed by fire. This building also stored public records.

Inspired by London’s Crystal Palace, this magnificent complex designed by Colonial Architect James Barnet was erected for the International Exhibition of 1879-80 on a 20-hectare site in the Royal Botanic Gardens stretching along Macquarie Street from the State Library to the Conservatorium. Instructions for plan preparation were given in mid-December 1878. Against all odds, with electric light permitting night shifts, nine months later on 17 September 1879, the Exhibition opened in the completed timber building. Most Exhibition buildings were designed as temporary constructions but few officials would order demolition after their initial purpose concluded. Suggestions to adapt the space for concerts, museums or lecture rooms were adopted while various public departments established offices on the basement floor.

Garden Palace, Sydney. The Graphic 26 April 1879.

Officials were baffled as to how the blaze started. Smoke coming from the dome was first noticed by the day watchman as he discussed changeover with the departing night sentinel. Entering the main hall they observed flames wreathed round a great bronze statue of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, rushing along pillars, leaping into the dome’s supporting beams. While one ran to the telephone to alert No. 2 Volunteer Fire Brigade, the other tolled the bell and released the watchman’s dog.

As the thirty-foot dome thunderingly collapsed inwards, sparks ignited a Potts Point roof and fiery ash reached Rushcutters Bay and Darling Point. Next the pediments and ten minor towers crashed, most concern being for the north side over Macquarie Street threatening the city centre as windows cracked along that thoroughfare. Fortuitously the wind changed direction before dozens of observers, many clad in night attire, were endangered. The Sydney Morning Herald reported on Saturday 23 September 1882, ‘By nine o’clock all was over, the residences in Macquarie-street had their view of the harbour restored to them, and ‘the pretty Garden Palace, whose grey-tinted dome could be seen lifted above the pine and fig trees – a beacon light to those incoming to our shores, the first object of beauty in the city as the Heads was passed – was a mass of smoking timbers and falling walls’.

The conflagration was relentlessly devastating as the entire edifice together with its contents were totally destroyed leaving a few stark brick pillars (formerly flanking the four main entrances) among smouldering cinders. Very quickly a loss inventory was compiled. Charles E. Moore, curator of the Botanic Gardens, for 48 years (1848 to 1896), calculated that between 20,000 to 30,000 plants were incinerated, charred pine trees undoubtedly would die, while the renowned gardens which had elegantly enhanced the Exhibition, probably would never be restored.

Documentation held by public service departments stood no chance of survival. Harbours and Rivers had three branches in the building. Water supply engineers now on the verge of completing works for the Newcastle-Maitland districts despaired as plans and tracings burnt represented many years of preparation and fieldwork. A complete set of Darling River surveys covering both cross-sections and longitudinal drawings covering 344 miles also fell victim. Experts hoped a duplicate batch made by a Melbourne civil engineer would offset destruction of the originals. The inferno also consumed Railway Department blueprints and documents including field and level books, working outlines and final plottings associated with dozens of connections concerning Orange, Forbes, Cootamundra, Gundagai, Blayney, Carcoar, Bungendore, Cowra and Illawarra extensions. Additionally, all preliminary paperwork for a Grafton to Glen Innes link was torched as was ‘the plan of the trial survey between the district of the Clarence and New England, and all the field books connected therewith, that had reached Sydney only a short time previous to the fire’.

The Singing Flames – Garden Palace, Sydney Mail, 30 Sept 1882 p545.

Records of the Occupation of Lands Branch suffered irreparable damage. The entire official records of the colony’s pastoral runs, both original and amended descriptions, all arbitration settlements, entire files collected over twenty years plus property transfer details were consumed. ‘Much of the information which has been lost will never again be obtained. ’Three months earlier nearly all this material was stored at The Exchange before transfer to the Garden Palace.

Significantly all documentation generated by collection of the 1881 census, costing over £24,000 to amass, proved readily flammable. While complaining of the time taken to extract valuable statistical details of this colony, ‘the most important one of the Australian group’, its loss was a bitter blow with only ‘summary tables’ available for submission to Parliament. The Sydney Morning Herald’s account lamented missing information covering the growth of towns over the past ten years, together with ‘particulars concerning the national, educational, religious, social and conjugal conditions of the people … which was to have been placed in the hands of the Government Printer today’.

The cause was never established despite an inquest called in October 1882 to determine whether spontaneous combustion, an accident or even the act of a pyromaniac had contributed. Meanwhile, wild suppositions had circulated that the basement was full of explosive material, gas mains had blown up, the night watchman – a smoker – was careless, or even that Fenians were responsible. Others contended that selfish residents wanted to retain harbour views or trotting out an old chestnut, powerful people were trying to quash convict ancestry. The Sydney Daily Telegraph for 7 October 1882 examined several possible motives. ‘It had frequently been openly stated that the Mining Department had valuable treasures stored away, amounting indeed to some £50,000 worth’. Investigations proved that nearly all that trove was recovered and was rated at just £700. A total lack of evidence to support any sensible or outlandish, explanation ensured that the jury considered its verdict for only one hour and then announced they could not determine the calamity’s origin while recording that ‘We consider that the authorities are deserving of censure in not providing more efficient supervision over such a valuable property’.

Anniversaries remind us of these deplorable repository catastrophes prompting us to constantly value the huge collections preserved in safe places throughout centuries that so illuminatingly reinforce our research.

Thank you Jennifer for this informative blog. While I knew of the destruction of Dublin’s Four Courts building I had no knowledge of Sydney’s Garden Palace existence and the loss of irreplaceable documents.

I also wasn’t aware of the destruction of records in the Sydney Garden Palace fire, but knew of the palace and what a devastating loss it was, I’ve a feeling my great-grandfather mentioned it in his diary.

Bobbie (GSQ Blog Editor)