The Wheeler Project

One hundred years ago the world was engulfed in conflict. Men and women from every nation were conscripted or volunteered to fight when hostilities broke out in Europe in August 1914. Some 416,809 Australian men and women enlisted in the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF), the main expeditionary force of the Australian Army. By the end of the war, over 60,000 Australians had been killed and 156,000 wounded, gassed or taken prisoner.

One central Queensland woman who found herself in England at the outbreak of war made a unique contribution to Australia’s war effort. Her name was Annie Margaret Wheeler. Born 1867 in Dingo, Queenland, the eldest surviving child of Alexander Stuart Somerville Laurie and his wife Margaret née Stevenson, Annie was educated in Rockhampton, married Henry Wheeler in 1896, widowed in 1903 and found herself in London in August 1914 working as a probationer nurse in a hospital east of London. Mrs Wheeler recognised the logistical difficulties facing servicemen and women and their families in central Queensland because of war-time press censorship (keeping casualty reports out of newspapers so as not to diminish the enlistment rate) and the unreliability of the mails (ocean-going vessels were being sunk at an alarming rate); she maintained contact with as many of them as she could, keeping a detailed card index on each, corresponding with soldiers and nurses on the battlefield; she liaised with their families, forwarded mail and parcels, supervised their care in hospital and provided financial assistance during their recuperation in England.

Mrs Wheeler’s fortnightly letters to Queensland newspapers kept families in touch with their sons and daughters and siblings, and provided reliable information to the Australian public about the men and women in the trenches. Grateful families responded by establishing a fund to support her work. By war’s end Mrs Wheeler’s card index contained the name, rank, service number, military unit, next of kin and location of more than 2300 Queenslanders. In recognition of her efforts, the Australian Government provided ship’s passage for her return to Australia in 1919. When her train arrived in Rockhampton in 1919 more than 50,000 people (many of them returned soldiers) cheered the arrival of Annie Wheeler, the ‘Mother of Queenslanders’.

Volunteers of the Genealogical Society of Queensland are transcribing Mrs Wheeler’s index cards, cross-checking the data against the files of the National Archives of Australia (NAA) and Queensland Justice Department to produce a ‘snapshot’ of Queenslanders who served in WWI. Whether you have an ancestor who served in the A.I.F., or know someone who might, or are interested in perusing this important historical collection, you will soon have on-line access to the name, birthplace, vital dates (birth, marriage, death), military serial number, rank and unit of Queenslanders who served in the Australian Imperial Forces 1914-1918. The data set will be available via the GSQ website (www.gsq.org.au/); a name index will be included on the website of The State Library of Queensland (www.slq.qld.gov.au/). Plans are in train to invite contributions from the public to augment the data with additional biographical details and photographs.

Working on the Wheeler Project is a visceral experience. The NAA files include enlistment documents that give a glimpse into the pre-war lives of Queenslanders – station-hands, shearers, railway porters, postal workers, nurses and doctors, cooks, solicitors, graziers. The NAA files also include poignant letters seeking information on the whereabouts of soldiers and nurses: “I have had no word from my son but Mrs Wheeler tells me that he is in [such and such a battalion] stationed in France…”. Mrs Wheeler kept track of their whereabouts – where they were last known to have been stationed, their forwarding addresses, whether they were wounded or captured or killed in action, the names and addresses of their family members and friends.

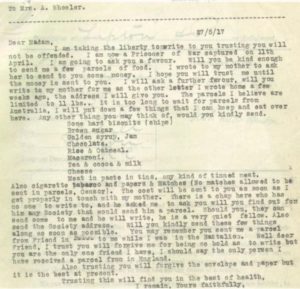

One letter to Mrs Wheeler from an Australian prisoner of war in Germany speaks volumes not only about the deprivation, loneliness and despair experienced by those in captivity, but about the trust and confidence Mrs Wheeler inspired in members of the A.I.F. and their families:

Mrs Wheeler’s index card for this man contains a notation that a parcel was despatched to him (and to his friend). The card also records his death the following year, still in captivity. His letter found its way into his NAA file, along with a letter to his mother from the representative of a society dedicated to maintaining the graves of Australian soldiers and describing the location of his resting place in a quiet wooded area on the outskirts of a German city.

Despite her best efforts, Mrs Wheeler was able to record only scant information about some individuals – a surname and military unit, or details of a serving family member (“brother Thomas, gunner, 4thPioneers, France”); in such instances, filling the gaps presents challenges for GSQ volunteers and in the process reveals some harrowing details – families who lost two or three or more sons in the conflict, their names following one after the other in alphabetical order in the data set. Individual stories come to light: a machine gunner requesting early release from duty owing to the death of his wife, leaving no-one to care for his children; wives enquiring whether their soldier husbands are alive and seeking early release of their husbands on compassionate grounds to help care for their children; a soldier’s request to his commanding officer for early discharge because his wife had died and he alone was left to care for their children. One file contains numerous letters from a woman trying to locate her wounded husband (spinal concussion and ‘ricked nerves’ – shellshock), asking whether he was still serving overseas, and the official response advising that he had been recuperated and returned to Australia in April 1919; it must have been a shock when she learned that he was home and that his application for a rail warrant to resettle her and the children in Rockhampton had been refused because he had already received the maximum allowance. His NAA file reveals that, as of 1922, the best efforts of the Army and the State Children’s Department (Qld) had been unsuccessful in locating him. His injuries and post-war financial difficulties must have had a profound effect on him and on the fragile woman who was left to care for the children. Research suggests that he lived for a time with his parents in Sydney, and then all trace of him vanishes. Perhaps his quality of life was degraded not only by penury but by the physical and emotional effects of his war injuries and the distress caused by inability to reunite his family. Or, perhaps the devastation wrought by his circumstances so overwhelmed him that he drifted into obscurity and died alone; his date of death has not yet been confirmed.

The Wheeler Project is one of many GSQ initiatives aimed at documenting the lives of Queenslanders and making the information widely available. Indices and data sets they might be but behind raw data lies the life story of each individual, whose descendants will have the opportunity to discover details of the war-time experience of their ancestor and to supplement the record with additional information.

Geraldine Lee

Pingback:The Wheeler Project. – GSQ Blog