Tracing your female ancestors.

I have recently given talks at GSQ and Brisbane City Council libraries on “Finding Grandma – tracing the female line.” It can be a challenge to discover a female ancestor’s individual identity; in the 18th and 19th centuries women were generally recorded as “wife of …” or “daughter of …” in a wide range of records. Socially, this situation existed as recently as the Second World War. How many times when doing our research have we come across a baptism record, for instance, which records the name of the child, its father, and no name, or only the first name of the mother. We cannot research her line any further until we discover her maiden name. This can happen generation after generation. In my family history program, I have recorded 19 females called Elizabeth; 15 called Sarah; 18 called Ann and variations. The winner (!) is Mary at 24 and this does not include Mary Ann or Mary A. How I long for the ancestors called Hephzibah (1), Phoebe (1) and Jemima (1). I have deferred research into finding maiden names for all of these women, as the majority are not on my direct line.

Mary Hall Paddock, 1874-1931

Some of the reasons why women’s individual identities are buried include an assumption that a female’s primary role in society should focus on the domestic or private sphere, despite the fact that women always worked. Women were not permitted to hold property in their own name, everything they owned became the husband’s upon marriage. This situation was not resolved until Married Women’s Property Acts were enacted at various times in the late 19th century. Women did not have the same educational opportunities as men and so they are missing from many records of professional and educational institutions. Women were often reduced to working as unskilled labour on the land, in factories, in mines, or in domestic roles in order to manage their households and child-rearing responsibilities. If a husband died, women who could not support themselves and their family either remarried quickly, or sought financial assistance from the parish or poor law organisations. Remarriage resulted in a new surname and often resulted in the birth of more children; parish and poor law records are at least one avenue for finding information about some female ancestors, although a reference to Widow Smith, for example, may not be that helpful.

All is not lost, however, especially towards the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century; depending upon the time period it is possible to find records of women at the different stages of their lives: birth/baptism, childhood, education, working life, marriage, family life, old age, death, burial, estate.

The Victorian era saw huge upheavals in society, as industrialisation gathered pace. In the UK, civil registration of births, marriages and deaths from 1837 and decennial censuses from 1841 onwards, saw females recorded as individuals. Civil registration in Australia commenced at different times depending upon the State concerned. In the UK in the late 19th century and up to the commencement of WW1, there was great pressure from middle and upper class women to have the right to vote, whereas this battle was won earlier in Australia. Electoral records are a useful alternative to census data. Women also sought greater access to education as this would open up careers such as teaching and nursing.

Taking all the above into account, here are some of the strategies offered to attendees at the presentation.

• Create a timeline for your female (and male) ancestors – this helps to set a framework for her life and focus your research on filling in the gaps.

• Start with the family – family photos, memories and memorabilia may have passed down a different family line; take all family stories with a grain of salt, but do not dismiss them completely until you have done your research.

• Family memorabilia may include photo albums, a family bible, heirlooms such as quilts, scrapbooks, jewellery, or vintage clothing; correspondence can shed a light on your female ancestor’s life; diaries.

• Record the information from all the documents you find, e.g. certificates, wills, educational/musical or other achievements, such as prizes and qualifications.

• Local and national newspapers can be an excellent source of information – the good, the bad, and the ugly! Copy can include detailed reports of marriages, funerals; family notices; obituaries, employment and social and community activities.

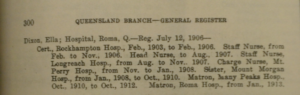

Australian Trained Nurses Association (ATNA) 1913-1914. Register entry for Sister Ella Dixon

• A death can potentially create 3 separate records: death certificate, funeral director’s record of burial, cemetery record of burial. In addition, there are potentially three other separate pieces of information: newspaper bereavement/funeral notice; obituary; in memoriam notice. Each record may provide a different piece of information. Memorial inscriptions on headstones should also not be overlooked.

• Wills can provide a great amount of detail on family relationships, property and other assets so are well worth researching.

• Divorce was not easy prior to the late 1800s, so many women and men just went their separate ways; this can cause problems in trying to find the ‘death’ of a spouse, and a second marriage. Divorces were often the subject of salacious and extensive reporting in newspapers.

• Women worked across a broad spectrum of professional, skilled, and unskilled types of work; education opened up training for new careers in teaching, nursing and office work or public service. Records, and their survival, often depend on the level of qualifications required to carry on that occupation

• Education also allowed women to move from one social stratum to another, e.g. from working class domestic service and factory work to middle-class teaching and nursing.

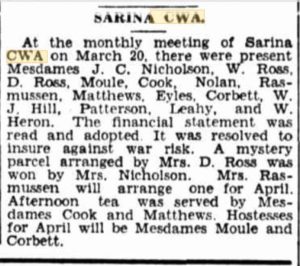

• Women often channelled their energies into the community as many paid employment options were closed to them after marriage. Women also filled the gaps left by men in times of war. Community groups include: church groups; Red Cross; Country Women’s Association; Women’s Institute; Guides/Scouts.

• Reports of fund-raising activities, e.g. cake stalls, fetes, are often found in social pages of local newspapers

Report on Sarina CWA, Daily Mercury, Mackay 4 April 1942

A useful resource for writing women into family history is by Noeline Kyle, Finding Florence, Maude, Matilda, Rose. Researching and writing women into family history, Unlock the Past. She offers some basic principles, such as: look for a wide a range of sources of information; use original records where possible. Investigating the laws, conventions and social customs of relevant eras helps to put your female ancestors’ lives into context. Researching the men, family, friends, and community can lead to individual women.

Researching the lives of your female ancestors gives you a fuller picture of your family history and is well worth the effort – you never know what you will discover.

Pauline Williams

An informative blog, Pauline. Non-genealogists would possibly not realise just how much society has shifted in the reporting of females over the last century. Without sounding sexist, at last women are now referred to by their correct names and possibly this ties in with the growing swell of equality over this period.

I agree with you Bobbie. As a follow-up to the stats in the post, I decided to try and put full names to each of the women in my family history program who were only recorded by their first name. I have so far managed to potentially identify about half of them, by cross-checking census records with GRO birth and marriage registration records and parish baptism and marriage records; the non-conformist church records are much more informative. I do now have the challenge of discovering who their mothers were, but as the majority are not in my direct line, I’m not sure how far back I will go. An ongoing task.

Thanks Pauline, This information will help me to reconstruct the lives of the women on the maternal side of my family. Yesterday when I was researching British newspapers, etc I discovered that there was an Irish female ancestor (my paternal family) who was into the Suffragette movement as were numerous other women back then. Makes for interesting reading.

Great blog post Pauline. It still amazes me, how women from the past, seemingly appear to be so overlooked in many records.

I was transcribing a will yesterday, and within that:

7. House I give her all these for her natural life and I give her

8. Twenty five pound a year She giving up her Marriage Settlement

9. to be paid her by my Exe[c]tutor every half year during her Life

Your post actually made me wonder, what does “giving up her Marriage Settlement” actually mean.

I presume she came into the marriage with land or money, but gave that to her husband upon marriage.

I googled it, this perhaps explains something towards the meaning in a small way.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marriage_settlement_(England)

Hi Robyn, Yes, I think she would have brought some land or money or other assets into the marriage and these were given over to the husband. He seems to be compensating her for that by giving her an annuity and a house to live in.