Family history revealed through death certificates

Many researchers consider it important to trace their ancestors from birth through marriage to eventual death and final resting place. My focus has been more on my ancestors’ birth, family, including parentage, and what they did during their life. As long as I have a date of death or burial, I haven’t always bought a death certificate to find out actual cause of death or sought out a final resting place; UK certificates are not as informative as Australian ones.

Recently, however, I watched a re-run of a Who Do You Think You Are? episode about the actor Martin Freeman. He was intrigued as to why so many children of one of his ancestors died when they were only young. Cause of death in most cases was ‘failure to thrive’ or equivalent. These ancestors in question were both blind. He sought advice from medical and other professionals and the most likely cause of the pattern of child deaths and the blindness was syphilis infection. The causes of death recorded on the death certificates and the pattern of deaths helped the professionals to reach this conclusion.

This started me thinking about whether there were any illnesses or other health issues that have been passed down through the generations in my own family. I hasten to add that I have no reason to believe that anyone in my family suffered from the same disease as those in Martin Freeman’s family.

The medical condition which we think has come down my maternal line relates to blood group and the condition called Erythroblastosis Fetalis. My daughter wrote an article, published in GSQs Generation (Vol 33, September 2010), which explained that this condition was also referred to as ‘blue babies’. It can occur when a mother with an A-Rhesus Negative blood group has a baby with an A-Positive blood group. This would presumably happen when the father also had an A-Positive blood group. The results of this condition can vary from anaemia to jaundice, miscarriages or death and tend to affect second or subsequent children if they are also A-Positive. It appears that the mother’s system builds up antibodies from the first A-Positive child which can pass through the placenta and overwhelm the baby’s red blood cells. The condition is easily treated now after the birth of the first A-Positive child. The publication of this article sparked off correspondence with GSQ member and medical professional, Dr A.P. Joseph, UK Corresponding Member of the Australian Jewish Historical Society, who provided a much more scientific explanation of the condition. I am sure Helen Smith would also be able to explain the genetics behind this.

It affects me because my blood group is A-Rhesus Negative, while my daughter and her father were both A-Positive. I remember receiving a rather large injection in my rear-end after my daughter was born. I’ve only had one child, so haven’t tested out the theory about blood group. I’m also not sure where this Rhesus negative factor entered my family’s genetic pool, but looking at other females within my maternal family, I suspect that both my grandmother and possibly my great-grandmother were both Rhesus Negative. Both suffered multiple miscarriages, had stillborn children or children who died at a very young age. Neither my mother nor my sister is Rhesus Negative, but one of my nieces is and she suffered miscarriages after her first child was born.

I mentioned earlier that UK death certificates are not as informative as Australian certificates. In preparing for writing this blog I decided to look through the certificates that I do have to see if there were any other patterns. Several males probably died from occupation-related illnesses: it seems reasonable that a cotton framework knitter would have bronchial problems as they would be breathing in the fibres. Joseph Hall died, age 69 years of chronic bronchitis, asthma as well as senile decay. George Paddock, a boot repairer, died aged 57 years in 1930 from myocarditis and congestion of lungs whereas Mary, his wife, died just 3 months later in 1931 from apoplexy, cardiac disease and myocarditis. This George’s father, another George who was also a boot repairer, had died in 1888 aged only 45 years, due to phthisis pulmonalis (tuberculosis). I wonder if all these causes of death affecting heart and lungs, were affected somehow by materials involved in repairing boots, or whether their environment contributed to their causes of death. I haven’t reviewed my paternal line, but as many of the males were coalminers it is more than likely that pulmonary illnesses caused their deaths. Senile decay appears as cause of death on several certificates. I could understand this for an ancestor aged 86 years at death, whose secondary cause of death was exhaustion, but I wonder whether this was a catch-all phrase for someone suffering a multitude of health problems.

My general advice to researchers has been to review the materials you have gathered. By looking at these certificates, I discovered that the informant to one death was the daughter of the deceased and gave her married name. I had not previously researched what happened to my great-grandmother’s other children and so this provides useful information. In another case, the informant was the sister of the deceased (Ann Paddock nee Brewer). As this sister (Maria Brewer) was as yet unmarried, I had added confirmation of the maiden name of my ancestor. The informant of another great-grandmother’s death was her grand-daughter with the very Lancashire surname of Leatherbarrow. This opened up a line of research to find out how she was related. My grandparents both died in hospital; my grandmother in 1972 aged 78 years from breast cancer; my grandfather in 1977 aged 89 years of cardiac failure. The name and address of the respective hospital was provided on the death certificate.

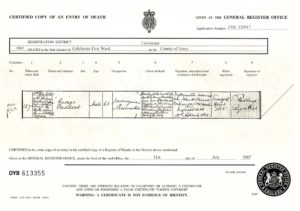

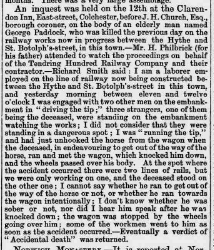

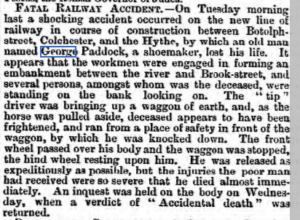

The most interesting death certificate was that of George Paddock, the first of a trio of bootmakers in my direct line. He died in April 1865, in Colchester, Essex, aged 63 years. He was the husband of Ann Paddock, nee Brewer, mentioned above. Cause of death was “Accidental and instant death by being knocked down by a ballast waggon on Railway the wheels going over and crushing the person’s abdomen and other parts of the body.” The informant was the Coroner. No Coroner’s report could be found, but the inquest was reported in great detail in the Essex Standard, a Colchester paper. Summaries were also found in several other papers. The inquest was interesting as the representative of the Railway company went to great lengths to exonerate the Company from any responsibility for the accident.

The most interesting death certificate was that of George Paddock, the first of a trio of bootmakers in my direct line. He died in April 1865, in Colchester, Essex, aged 63 years. He was the husband of Ann Paddock, nee Brewer, mentioned above. Cause of death was “Accidental and instant death by being knocked down by a ballast waggon on Railway the wheels going over and crushing the person’s abdomen and other parts of the body.” The informant was the Coroner. No Coroner’s report could be found, but the inquest was reported in great detail in the Essex Standard, a Colchester paper. Summaries were also found in several other papers. The inquest was interesting as the representative of the Railway company went to great lengths to exonerate the Company from any responsibility for the accident.

|

| Chelmsford Chronicle, 21 April 1865 |

|

| Bury & Norwich Post, 18 April 1865 |

I’m sure we all accept that we are not just buying death certificates out of morbid curiosity, but as a way of understanding the health problems faced by our ancestors. These problems could potentially be gifted to us through the wonders of DNA. Death certificates can provide information and leads for other avenues of research, although it is generally accepted that they can be unreliable. After all, the person who knows whether the information given on the certificate is correct or not, is no longer there.

Has information on a death or other certificate helped you to break down a brickwall, given you an interesting lead, or provided an explanation for something within your family?

Thanks to Helen Smith for sharing last week’s post about the GRO adding extra details to their indexes for births and deaths. I’ve been able to correctly identify several births now the mother’s maiden name is included.

Until next time

Pauline

Very interesting post Pauline. What a sad story about George Paddock, which probably makes you wonder what sort of a flow-on effect did his death have on his family at the time.

Bobbie