Tracing Chinese Ancestors

The story of Chinese immigrants is the story of every Australian, whether the journey was in the 19th or 20th or 21st Century, a voyage of three months or 20 hours by jet – the differences are of degree only. Chinese immigration to Australia was rare before the mid 1800s when gold was discovered in Victoria. Thousands of Chinese responded to the lure of mountains of gold awaiting anyone willing to work long hours panning and digging and living a hard-scrabble existence in remote areas. The first wave of Chinese immigration was welcomed because it was assumed that Australia’s future prosperity lay in a regular stream of immigrants who would populate and develop the vast empty spaces in the interior and the far north of Queensland. Chinese immigrants proved to be law-abiding and hard-working. They followed the trail of gold strikes from Victoria to New South Wales and eventually, in 1874, to Palmer River in North Queensland. When the gold played out and socio-political views of Asian immigration changed, most Chinese immigrants (some 15,000 in Palmer River alone) chose to stay in Australia despite increasingly restrictive legislation designed to encourage their return to China. They migrated from the goldfields to outback towns or the fringes of capital cities, pursued other occupations (or invented their own) and took up the challenge of making Australia home

The descendants of these Chinese-Ausralians face unique challenges in trying to trace their ancestors. Most genealogy research begins with, at the very least, a surname, but every Chinese immigrant had to adopt a name that could be pronounced and written not in Chinese characters but in English. Determined to integrate, culturally programmed not to offend, driven in almost every case by the prospect of a vastly enriched life in Australia, the Chinese willingly accepted the name change. When confronted by a ship’s crew member or port officer, pencil in hand to record the name of passengers entering Australia, the Chinese immigrant responded with what he took to be an English version of his name (and probably strained every muscle trying to remember how his new name sounded when pronounced by the English-speaker). [The language here is deliberately gender specific: the first waves of Chinese immigrants were exclusively male. Chinese women immigrated later, as wives of the men who came during the gold rush; these women usually retained their maiden name, but in some cases added the husband’s family name to their own – good to know when researching a female Chinese ancestor.]

Chinese practice is to write the family name first – an important clue when researching a Chinese ancestor. There are more than 700 Chinese family names but only 20 of these are in common use in Australia. International travel in the 1900s was by no means the formal orderly process that evolved later; assuming that a Chinese immigrant of the period possessed a travel document, that document would have been written in Chinese characters – indecipherable to an English-speaker.

Male Chinese immigrants used ‘Ah’ (which translates roughly as ‘Mr’) as part of their anglicised name. The archival records of incoming passengers and crew during the last half of the 19th Century have long lists of entries beginning with ‘Ah’ – indexed under ‘A’ – Ah Chang, Ah Foo, Ah Peng, etc, followed by a name that corresponds (in Chinese) to the occupation – ‘Ah Chen’ (old), ‘Ah Ding’ (gardener), ‘Ah Sun’ (grandchild, descendant), ‘Ah Yuen’ (musician or musical instrument). To compound the confusion, the name recorded by an English-speaker was an interpretation of the sound and spelling of the name, eg., the family name ‘Foo’ was variously recorded as ‘Fou’ or ‘Fhou’ (sometimes all 3 spellings were used for the same individual across various documents and periods of time). Given all the variables, searching for a Chinese ancestor in a ship’s manifest or an index of ‘aliens’ can be a gruelling task.

But persistence and knowledge of the social and political climate of the period pay off: persistence, because the search requires time and patience; background knowledge of the times in which your ancestor lived, because historical perspective may hold clues that help to identify him. Your ancestor may have come to Australia to mine for gold, as did my husband’s grandfather, a Cantonese who became known as Sam Foo when he arrived in Melbourne in 1874. I eventually found various documents for Sam (alien registration, mining licence, application for naturalisation). With persistence and some background information about Chinese immigration in the latter half of the 19th Century, I found records that matched the known facts of Sam’s life: born in Guangzhou (Canton) in 1856, arrived in Australia as a 19-year old to work at the Palmer Goldfields, eventually settling in Surat, Sam and his Lancastrian wife Kate raised four children, one of whom was my mother-in-law. I have yet to find Sam’s immigration record, possibly because along with hundreds of other Chinese arriving in Australia during the gold rush years, he used the name ‘Ah Foo’ (Mr Foo), or because English-speaking Customs officials would not necessarily have known that ‘Ah’ was not a name but a title and so did not require a ‘first’ name; or perhaps because at arrival in Melbourne Sam’s knowledge of spoken English was minimal and he did not understand what was being asked of him.

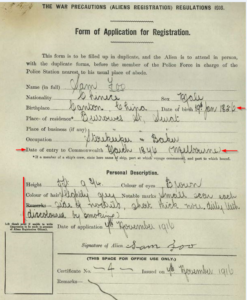

The documents that positively identify Sam as my husband’s grandfather came to hand after several years’ search of microfiche and on-line records, mostly with nothing to show for the time and effort. I remember feeling as though the research phase might never end but, in retrospect, I needed only to find one thread in a huge tapestry (a single document) and Voila! Sam Foo began to appear! Although I have not found a document that includes the Chinese characters of Sam’s name, his 1916 alien registration confirms his date of birth, date and place of arrival in Australia, occupation, address and – most precious of all because there are no photographs of Sam – a physical description:

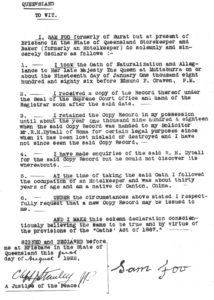

Sam’s signature on this document was important in authenticating earlier documents which I did not find until much later: his application for naturalisation (1885) and his affidavit seeking replacement of the original certificate of naturalisation (1922). The 42 years between his arrival in 1874 and his alien registration in 1916 revealed that by 1922 Sam had left Surat, moved to Brisbane and was contemplating a return trip to China with his wife Kate and four children, and needed his

Queensland State Archives, 882268/7569, ‘Combined Index to Naturalisations 1851-1904’ (1886/ Z2206)Sam’s arrival in Melbourne in 1874 and his alien registration in 1916 remained a mystery until a subsequent discovery

certificate of naturalisation in order to obtain a passport. He swore out an affidavit that unlocked the events of those 42 years.

Twelve years after Sam’s arrival he took the Oath of Naturalisation and Allegiance at Muttaburra (confirmed when I found his application for naturalisation, outlining all the events of his life between 1874 and 1885: his work in Copperfield, Palmer River and Muttaburra, and his first marriage – previously not even remotely suspected by the family). Proof that Sam worked as a hotelkeeper came in the form of a business licence issued at Palmer River in 1876, suggesting that he may have tried his luck at gold mining but realised that his talents lay elsewhere. A business license allowed him to trade not only in gold but in other goods; he established a trade store, prospered in business and may even have taught himself to bake bread (his principal occupation for 20 years).

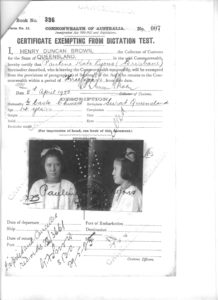

CEDT for Pauline Lyons* age 14, April 1922 (NAA, J2483, 336/006-9)

Once again, an understanding of the past helped to reveal Sam’s life in the years between 1888 (when he left Muttaburra) and 1903 (when he showed up in Surat). In the late 1880s, dreams of a gold-fuelled Australian economy had faded as the gold failed. There was widespread debate about what to do with the thousands of Chinese who had immigrated to work the goldfields of Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland, and impassioned debate about the importation of more (and cheaper) Chinese labour for the sugar plantations and the expansion of Queensland’s railways. There was economic recession and substantial unemployment at the time, and it was deemed not just illogical but detrimental to Australia’s future as part of the British Empire to continue to import Chinese who would compete for a dwindling number of jobs . Anti-Chinese leagues sprang up in major cities across Australia, with protests and demonstrations in 1878 and 1880 in Sydney, 1888 in Melbourne and in country towns (including Clermont). Sam negotiated these turbulent years by adopting a quiet lifestyle in outback Australia, but by 1922, after retiring to Brisbane (he is listed in the 1922 Brisbane Post Office Directory), he decided to re-visit Canton with his wife and four children. He obtained certificates of exemption from the dictation test (CEDTs) for each of his children in 1922.

[* The births of all of Sam’s children were registered under their mother Kate’s name (Lyons) and separately under Sam’s name (Foo); Pauline was my mother-in-law; the discovery of her CEDT provided the only early photograph we have of her.]

When Chinese Australians travelled abroad they were obliged to apply for an exemption from the dictation test to ensure that they were not denied re-entry to Australia, because the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 stipulated that individuals unable to write 50 words of dictation in a language specified by the Customs officer could be denied entry to Australia [emphasis added]. The practical outcome of the Act was to restrict the number of Chinese entering Australia and to control re-entry of those who had left Australia then tried to return. The Chinese were not singled out in the language of the Act but the dictation test could be administered in any European language (subsequently altered to ‘any prescribed language’) and could be administered within a year of arrival (later extended to two years in 1910, three years in 1920 and five years in 1932). The test was probably used to greatest effect between 1901 and 1905, when port officers tested and refused entry to more than 700 immigrants and returning residents. Legal challenges to the test rose markedly in these years, and again in the late 1940s and 1950s, in actions in the High Court of Australia involving wartime refugees and others. Abandoned in 1958, the Dictation Test endures in popular historical memory as a cornerstone of the White Australia Policy (National Archives of Australia: Paul Jones, Chinese-Australian Journeys, Regulation of Arrival, Settlement and Movement, p. 18).

I found Certificates of Exemption from the Dictation Test for all four of Sam’s children, each bearing the notation that the exemption issued in 1922 had expired by 1925 (proof that the trip did not take place). Along with Sam’s application for a replacement certificate of naturalisation, the CEDTs for the children prove that Sam planned to travel abroad, the obvious and most likely destination China, because Chinese immigrants customarily sent their Australian-born children back to China for education or to visit relatives. One of Sam’s grandsons tells an interesting story about the reason that the trip did not eventuate: the family were at the dock (presumably in Brisbane) and as the children began to ascend the gangplank, Kate overhead a crew member joking that they would be targets for child abductors in Hong Kong or Canton. Kate apparently had reason to believe that this might happen, and she marched back down the gangplank and presumably prevailed upon Sam to abandon the trip. This family story is substantiated by the fact that no evidence has been found that the family travelled to China in 1922 or in any year leading up to Sam’s death in 1936.

Sam’s name does not appear the rolls of any of the electorates in which he lived between 1914 (when voting became compulsory) and his death in 1936. Despite being a documented citizen of Australia, Sam did not exercise his right to vote, but then again, having worked the whole of his adult life in this country, he wasn’t eligible to receive the old-age pension – because he was Chinese. During his 62 years in Australia, there is no evidence that Sam broke any law or caused damage or detriment to anyone. Thirty years after his naturalisation he was required to register as an alien and face the possibility of internment for the duration of World War I. It occurs to me that Sam was indifferent to his obligation to vote because he saw no evidence that Australian officialdom acknowledged his status as a citizen.

‘Tracing Chinese Ancestors’ will continue Monday 23 January with information about the repositories in which documentary evidence of Sam’s life was found – and in which evidence of your Chinese ancestor might also be found.

Geraldine Lee

Thanks for sharing Geraldine, as always I really enjoyed the blog. Bobbie

Thanks Bobbie. See you at writing group later this month.

A fascinating story, Geraldine. Researching Sam Foo has required incredible persistence. I look forward to part 2 to find out the range of resources you accessed. Pauline

Thanks Pauline. See you at writing group later this month.

Geraldine I now know that “Ah” is mister and not really a name. thanks MargD

I remember the ‘ah-ha’ moment when I discovered the link between ‘Mr’ and ‘Ah’, no pun intended. Saved me a lot of useless searching. Thanks for your comment Marg.