Census substitute or historical snapshot?

by Bob McAllister

I thought that I had become quite adept at using the 1939 Register since it became available in November 2015 [1]. After all, it was just like a census released early with the bonus of full dates of birth offset by the absence of place of birth – valuable, but hardly exciting. However, in the last few days I have come to view this resource in quite a different light.

It began at the GSQ Annual Seminar for 2018 where the theme was My Favourite Source [2]. The very first speaker was Stephanie Ryan from the State Library of Queensland praising the Register. How would she convince anyone that this very ordinary (albeit extremely useful) dataset was enthralling? While explaining the reason for records to be “closed”, Stephanie commented that it seemed that details of a disproportionate number of guests at the Ritz Hotel remained hidden and mentioned that even Buckingham Palace could be searched as an address.

My interest was piqued but, with other pressing tasks, I filed away for later the idea of exploring places in the Register, until I was reviewing the records I had on one Leonard Graham Brown (born in Queensland, Rhodes scholar, WWI Military Cross winner, England Rugby captain, distinguished surgeon). I noticed that My Heritage offered a record showing his residence in September 1939 as Charing Cross Hospital, Agar Street WC [3]. Was this drawn from the Register and who else might have been resident at that same address?

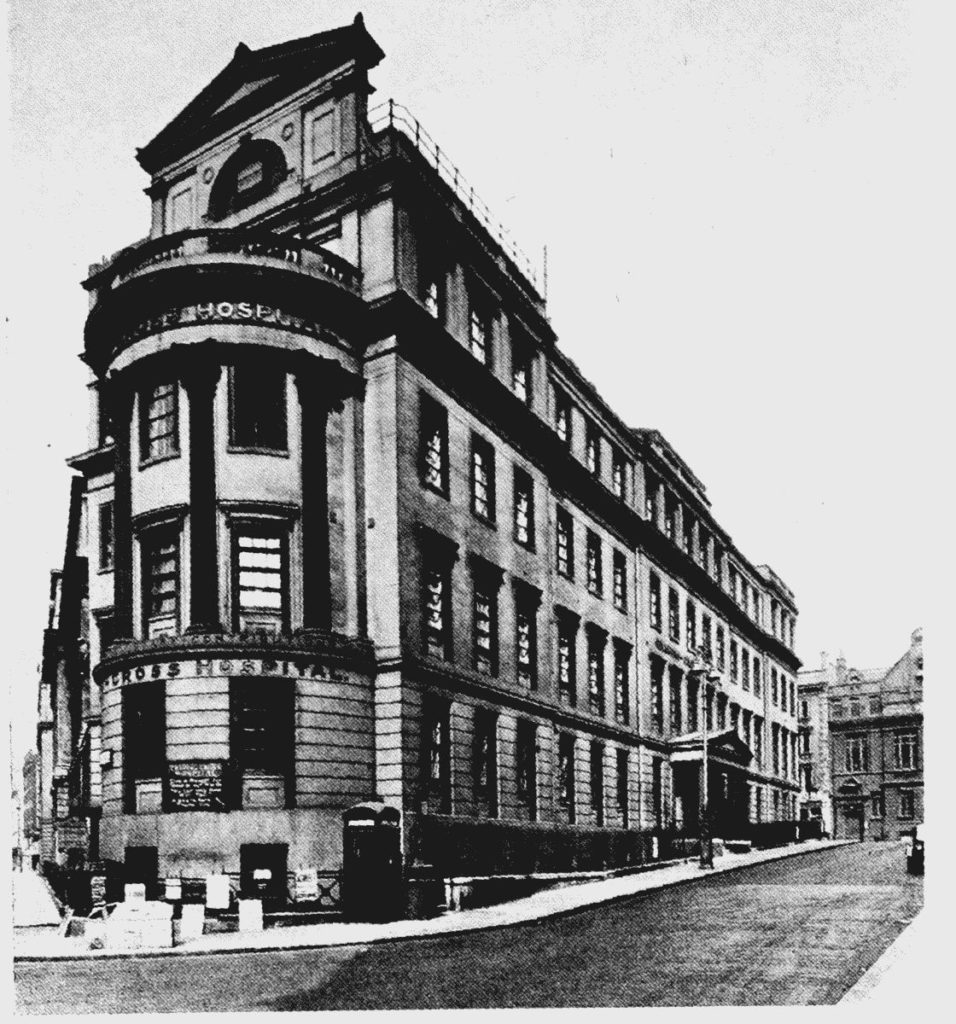

Charing Cross Hospital in 1939. Elevation to Strand and Agar Street [4]

What was revealed was a veritable cornucopia of records of people related not by family ties but by location, and economic or occupational connections. There were 129 individuals recorded of whom only 14 were closed for privacy reasons.

The 115 named individuals were made up of:

- 35 patients

- 13 doctors

- 41 nursing staff

- 12 medical students

- 4 ancillary medical staff

- 10 domestic staff.

Because of the order in which groups of names were entered, it is possible to draw reasonable inferences about the status of the other 14 (possibly living) people; viz 7 nurses, 4 medical students, 2 domestic staff and 1 patient.

66% of the patients were male and 66% were (or had been) married. Single women made up just 6% of the group. Only 1 of the 8 married women listed an occupation other than “housewife”. (She worked as a Chemical Laboratory Assistant) The youngest patient was 16 years old and the oldest 72 (both males). The age range for female patients was 33 to 69. Although 5 of the patients were over 65, none was described as retired.

All of the 13 doctors were male and listed post-nominals in describing their occupation. The more senior the qualification held, the less likely they were to include others. Three of the four Fellows of a Royal College used just FRC*, but all of the mere Members of those colleges added their primary qualification(s). The two doctors not yet admitted to one of the prestigious Royal Colleges (perhaps not coincidentally, the youngest) seem to have provided all their university attainments, including a BA.

The (named) nursing staff were all female and (with just 3 exceptions) single. 17 were fully-qualified “Sisters” and 7 others were described as “Registered” or “Trained”. They were responsible for the work of 17 Probationers. One of the Sisters was specifically designated the Tutor Sister. It seems probable that the 7 nurses whose records remain closed were also in training.

Dr Leonard Graham Brown born in 1888 (my original search target) was the oldest doctor but still more than 8 years younger than Matron. The oldest staff member was the Head Porter who had been born in 1874.

It seems puzzling that the hospital had a Head Porter but no staff apparently answering to him; particularly when photographs of the hospital taken 40 years earlier show large groups of male “porters”. By 1939, their roles (moving patients, bandaging etc) may have been taken over by the surprisingly large group of young men whose occupation is described in the Register as Medical Student Attached As Dresser To Charing Cross Hospital (possibly a part-time appointment around their formal studies).

In addition to the Head Porter, the ancillary medical staff included two Radiographers and a Librarian (who may have been responsible for keeping the hospital records).

The last occupational group was made up of a Cook and 9 Domestic Servants who must have been responsible for food preparation and service and cleaning – tasks which would have been regarded as part of the work of nurses in earlier times.

Who could have imagined that a single record in The 1939 Register could provide such a rich description of a slice of life from our history. And I have not yet considered the other 114 names (with full dates of birth) to be explored. Since they were at the hospital (rather than at home) on the day that the register was compiled, I do not have each person’s usual place of residence but that ought to be readily accessible through the London Electoral Registers.[5]

What was the catchment area for the hospital in 1939? Was the staff drawn from the same (or similar) areas as the patients? Did any of the patients die in the period after the Register was created? What became of these 115 people when war broke out? The possibilities for further investigation seem endless, and I think I have a new favourite source!

Postscript: The current location of the facility named Charing Cross Hospital is in Hammersmith. During the Blitz, the entire hospital (staff and patients) relocated to Hertfordshire under the medical superintendence of Leonard Graham Brown, who also oversaw the return to Agar Street in 1947. The final move to a modern purpose-built facility took place after his death (at the Hospital) in 1950. The building shown in the illustration is now the Charing Cross Police Station [6].

References

[1] https://blog.findmypast.co.uk/announcing-the-release-of-the-1939-register-1424355718.html

[2] https://www.gsq.org.au/event/annual-seminar-favourite-source/

[3] https://records.myheritagelibraryedition.com/research/record-10678-3076723/leonard-graham-brown-in-1939-register-of-england-wales

[4] “Plate 38: Charing Cross Hospital and Morley’s Hotel.” Survey of London: Volume 20, St Martin-in-The-Fields, Pt III: Trafalgar Square and Neighbourhood. Eds. G H Gater, and F R Hiorns. London: London County Council, 1940. 38. British History Online. Web. 2 November 2018. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol20/pt3/plate-38.

[5] Ancestry.com. London, England, Electoral Registers, 1832-1965 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Citing Electoral Registers. London, England: London Metropolitan Archives.

[6] Link to Google Maps

Fascinating stuff, Bob. I constantly drift off on such tangents, but gain a fuller understanding of life in the communities.

You must write a book about it!