Convict Stories – Life after Transportation

For many years Australians regarded convict ancestors with distaste and did their utmost to distance themselves from this part of their ancestry. However, many convicts had a huge impact on the development of Australia; the punishment that was meted out to them, not only in England, but also in Australia, was often incredibly harsh. From my recent research into the lives of three convicts, I think we could argue that these were not all the ‘bad apples’ the English justice system made them out to be. I have been fascinated by the stories of these convicts.

Thomas Trot(t)man was transported in 1821 on a charge of grand larceny. The Windsor and Eton Express of 4 March 1821 reported that he and a fellow conspirator broke into a cellar and stole ale and beer. Thomas was a shepherd at the time of his arrest, so perhaps he intended to on-sell the alcohol for a profit. They were both sentenced to transportation for seven years and arrived in Van Diemen’s Land on the Malabar; Thomas left behind his wife Mary and two children.

Thomas’s gaol report described him as of ‘very bad character’ whereas his hulk report considered him ‘quiet and orderly’. His convict record listed only one transgression. In October 1824, accused of neglect of duty, absence from the farm where he had been assigned, as well as insolence, Thomas received 25 lashes for these infringements. He appeared to adjust to his new situation and received his ticket of leave in 1826 and his freedom in 1828.

Thomas’s gaol report described him as of ‘very bad character’ whereas his hulk report considered him ‘quiet and orderly’. His convict record listed only one transgression. In October 1824, accused of neglect of duty, absence from the farm where he had been assigned, as well as insolence, Thomas received 25 lashes for these infringements. He appeared to adjust to his new situation and received his ticket of leave in 1826 and his freedom in 1828.

At some stage, Thomas’s wife Mary Brooks joined him in Hobart Town where a daughter Eliza was born in 1831. Initially working as a labourer, Thomas also served as a constable according to the Launceston Advertiser of 29 January 1835. Thomas and Mary already had a daughter Elizabeth, born about 1821, possibly shortly before Thomas was convicted and transported. Perhaps the birth of this child and lack of employment had been the motivating factors behind his crime.

Upon arrival in Hobart, Thomas was assigned to Public Works where he most likely learnt brickmaking – a skill that he took with him when he left Tasmania. Thomas and Mary were among the first group of settlers in Port Phillip in Victoria when this area was opened up. They are recorded in the 1841 census with 7 children. By 1847 Thomas and Mary were living in Batman’s Swamp where he had established himself as a brickmaker. Subsequently the family moved to Fitzroy in Melbourne.

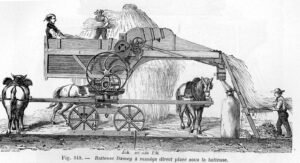

Not long after Thomas Trotman had gained his freedom and had been joined by his wife Mary, a group of convicts arrived on the Eliza, convicted of ‘machine breaking’, i.e. feloniously damaging a threshing machine. This group included a father and son Arthur and George Binstead. The Trotman and Binstead families would subsequently be united through marriage.

Drawing of a horse-powered thresher from a French Dictionary of Industrial Arts, published 1881. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swing_Riots

Many rural workers were convicted of machine breaking during the Swing Riots in England in the early 1830s. The introduction of threshing machines threatened the livelihood of many agricultural labourers. Their actions were analogous to the Luddites who damaged knitting machines, especially in the Midlands. Damage to property was considered a serious crime and perpetrators were treated extremely harshly. Although Arthur and George were sawyers rather than agricultural labourers they may have joined in the machine breaking activities in Sussex in support of their fellow agricultural workers. Both father and son were convicted on two counts of machine breaking and sentenced to seven years transportation on each count – a total of 14 years.

As sawyers Arthur and George would have been in great demand in Van Diemen’s Land, where sawn timber was required for construction and many other purposes. They were initially assigned to Public Works, although Arthur at least was later assigned to a pioneer settler. Whereas Arthur seemed to accept his lot, George most likely found convict life difficult. He was only 17 years old when he was transported and his immaturity probably explained the number of offences he committed while serving his sentence. He was found guilty of seven offences between 1832 and 1835, mostly related to drinking and disobedience. On 24 December 1834 he was convicted of stealing and eating a fellow prisoner’s food; as part of the punishment, his meat ration was delivered to the other convict. Shortly afterwards, he was charged with taking a saw from a building site to work for his own benefit without permission. In this case, he was sentenced to 14 days in leg irons. Perhaps the authorities in England realised the severity of the punishments meted out to these machine breakers was excessive and free pardons were granted in April 1837. At some stage after this, Arthur’s wife, Maria Horn, was funded by her local parish in Sussex to travel to Hobart with some of their children to join him and their son George. This would have relieved the parish of having to support the family.

It is not surprising that the Binsteads and Trotmans would have known each other as the population of Hobart Town must have been quite small. A year after George was granted his free pardon he married Elizabeth Trotman on 16 April 1838 at St David’s Church in Hobart. Both families would have weighed up their future options after they were free. In both cases, they even adjusted some of their personal details to remove any suggestion that they were convicts. This can create problems when attempting to create a timeline for their life in Australia.

The Binsteads, George and Elizabeth, and Arthur and Maria, left Hobart in 1838 or 1839 and travelled to South Creek in the Penrith district of New South Wales. The family ran a carting business in St Mary’s. They chose the Penrith area as John, George’s older brother, had also been transported in the early 1830s, but to NSW rather than Van Diemen’s Land.

Binstead’s sawmill, Queen’s Wharf with timber stacked up on Lot 4. Section from an 1888 drawing. queenswharf.org/people/the-binstead-family/.

The two branches of the family eventually separated. Arthur, Maria and John moved north to Brisbane; there they established the first sawmill on the banks of the Brisbane River, on the site where the Queen’s Wharf project is currently under way. Arthur had bought land there as early as 1843. The family prospered and were joined by other relatives, who arrived as free settlers from England. Arthur sadly died in 1851 and it is stated that he was buried at St John’s Church in Brisbane. Members of the wider family then settled in the Coomera/Upper Coomera area in the Gold Coast hinterland where they became highly respected members of the local community. Explore the connection of the Binstead family to the Queen’s Wharf site at http://queenswharf.org/people/the-binstead-family/.

George and Elizabeth, on the other hand, relocated to Fitzroy in Melbourne to join Elizabeth’s parents, the Trotmans, sometime between 1853 and 1856. They had had eight children in NSW and would have a further three in Melbourne. George’s widowed mother Maria subsequently joined them. After his experiences as a convict, George may have preferred the freedom and independence as a carter, with his own horse and dray, rather than continuing in the sawmill business. In due course, he became a Freemason and a respected member of the Fitzroy community.

Tragically, he was not to enjoy the fruits of his labours for too long as he died in an accident on 13 April 1867. The Argus (Melbourne) of Tuesday 16 April 1867 carried a report on the inquest.

“Dr Youl held an inquest yesterday, at Carlton, on the body of George Binstead, fifty three years of age. On Saturday last the deceased drove his horse and dray up a right-of-way in Fitzroy, leading to his house; the dray was crossing a trench which had just been made and the deceased, who was sitting on the guard-iron, was jerked off, and fell upon his head. Before a doctor could arrive the deceased died. The jury returned a verdict of accidental death.”

George was buried in the Methodist section of the Melbourne General Cemetery in Carlton North. His wife Elizabeth outlived him by 20 years, dying on 28 January 1887; she was buried alongside him.

What of Thomas and Mary Trotman? When Mary died in December 1879, the Camperdown Chronicle, Friday 2 January 1880, p.3 reported:

“The death of an old colonist was registered at Fitzroy on Friday last, viz. that of Mrs Mary Trotman, wife of Thomas Trotman, who came to the colony with her husband in 1836. The noticeable circumstances in the history of the pair were that they had been married 63 years, and that their lineal descendants numbered 100 individuals. They originally arrived in Tasmania in 1833, and came over four years later to Port Philip, with one of the earliest parties of settlers. Mrs Trotman reached the age of 85, her husband who is still living, is 90.”

It can be assumed from this report that the Trotmans’ move to Victoria enabled the family to reinvent the details of their arrival in Tasmania. How would anyone find out the truth in those long-ago days? Thomas himself died in January 1881 and was buried at the Melbourne Cemetery. In his will he was described as ‘gentleman’.

The Trotman and Binstead families were perhaps not untypical of many who arrived in Australia in less than auspicious circumstances. However, moving to Australia gave them opportunities which they would probably never have had back in their homeland. Their descendants have to thank them for that.

Pauline Williams

Notes and sources:

Ancestry.com.au has a wide range of convict records and documentation;

Newspaper articles were sourced from Trove at Trove.nla.gov.au and The British Newspaper Archive at https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/ and www.findmypast.co.uk.

Jill M. Chambers, Machine Breakers, Tasmanian Ancestry, Journal of the Tasmanian Family History Society, vol 36, No. 1, June 2015. Reprinted in this journal with permission from Descent: The Journal of the Society of Australian Genealogists Vol. 19 Part 3 (September 1989), pp. 112–15.

Bruce W. Brown, The Machine Breaker Convicts from the Proteus and the Eliza, MA Thesis, University of Tasmania, 2004.

Thanks are extended to Professor Hamish Maxwell-Stewart of the University of Tasmania for providing information from the University’s database of Tasmanian convicts, and also for his fascinating talks on the UTP Tasmania cruise conference in March 2020.

Great report on the Trotmans and Binsteads. Thank You

I am collecting information on this family for a family in Melbourne who had been searching for their mother’s identity.

This is my third encounter with swing riots in my searches for the Circular Head Heritage.

Hello Bronwyn, thank you for your comment. The blog post arose from extensive research that I conducted for one of my daughter’s friends. She was descended from the Trotman and Binstead families. The Binsteads were transported in 1832, convicted of machine breaking as part of the English swing riots. The two families eventually left Tasmania and connected through marriage in Victoria. I provided some helpful references in the blog post. The University of Tasmania thesis that I mentioned is especially helpful about the convicts, as are the convict records that are now online. Best wishes for your research. Pauline

Hi Pauline,

I am currently researching a block of land in Bathurst Street Hobart that was first located to Thomas Trotman. I know the owner of the current house on the block which I suspect was built in the 1850s. There was house there in 1836 after Thomas no longer owned the land, but two houses are mentioned for a couple of years in the 1850s and then it goes back to one. I suspect the original was demolished at that time. The property was eventually granted in 1844 to the fourth owner, Thornton Bowden. I have the grant document and other details. I am happy to be contacted, My email is available on the Libraries Tasmania website where I am a voluntary researcher in family history and DNA research. https://libraries.tas.gov.au/get-help/help-with-research-and-finding-information/private-researchers/

Hello David, thanks for your information. I’m no longer actively researching in this area. Hopefully the person who made the initial comment in this thread will see your comment and follow up with you if it helps their research. It’s a fascinating topic, but I’ve just had to focus on my own research. Best wishes, Pauline