Family lost and found

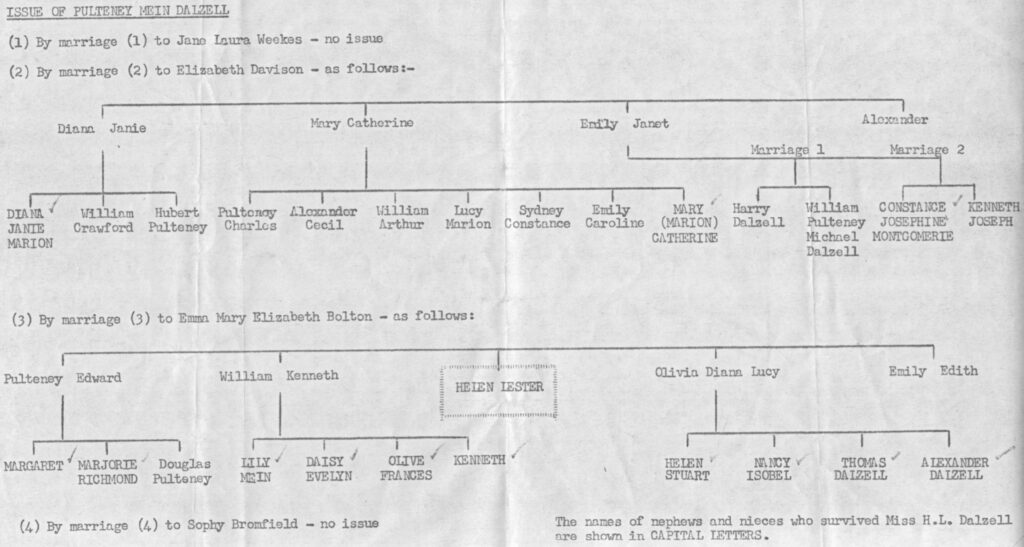

In a box of family papers is a paper headed “ISSUE OF PULTENEY MEIN DALZELL”. There’s a note at the bottom: “The names of nephews and nieces who survived Miss H.L. Dalzell are shown in CAPITAL LETTERS.” Miss H.L. (Helen Lester) Dalzell is listed in the bottom-most line of children. Looking at other items in the box, it’s clear that Helen was ‘that person’, the one that kept in touch with all her relatives and passed on news of family events. It’s not known who typed up this paper, but it appears to be summarising information provided by Helen herself. What a boon to a family historian her list seems to be!

Children of Pulteney Mein Dalzell.

Until… I compared it to the output from my painstaking paper-trail research into my 2x great grandfather, Pulteney Mein Dalzell. Missing. Not named. Not known about, or not talked about. Who is to know, with the distance of time.

I suspect that Helen knew nothing of her father’s first marriage, not because of any scandal but simply because he simply ceased to mention it when he moved to India from Britain in 1835. He was just 24 when he married Elizabeth Louisa Wilday in Birmingham in 1833.[1] The records are stubbornly silent on why he moved there from his birthplace Edinburgh, as well as the fate of his wife. Their child, Pulteney Malcolm died when three months old.[2] Eight months later Pulteney was on a ship to Bombay with no further mention of Elizabeth.

I’m pleased to recognise Elizabeth Louisa and her baby boy Pulteney Malcolm and return them to their place in my family.

Helen’s paper lists his first wife as “By marriage (1) Jane Laura Weeks – no issue.” Oh my dear Helen, there was indeed issue. And tragedy.

Pulteney married Jane in Bombay on 10 March 1838, three years after arriving in India.[3] Then, in the English newspaper Morning Post, Thursday 31 October 1839 under the headline “DEATHS”: “On the 29th July, the infant daughter, and on the 30th, the beloved wife of P.M. Dalzell, Esq., aged 21 years”.[4] The phrasing of the notice suggests to me that Pulteney was devastated by these deaths.

I recognise this unnamed baby girl, carried under Jane’s heart for nine months, and record her place in my family.

The next line on Helen’s paper is “By marriage (2) Elizabeth Davidson – as follows”. Pulteney remarried three years after Jane’s death when on leave in England, leaving for India with 18-year-old Elizabeth soon after.[5] What must he have felt when she was about to give birth just two weeks after arriving in India. Would this child live? Would this wife survive? Thankfully all went well. Elizabeth and Pulteney had seven children in all, but Helen’s paper lists only four of them. Perhaps she never knew of the two who died so young. Elizabeth’s fourth child, Lizzy, died of dysentery in Bombay two days after her first birthday.[6] And the youngest, Constance, was nine when she died in Edinburgh after a lengthy illness.[7] Constance’s mother died of fever in Kurrachee (Karachi) on Boxing Day, 1855.[8]

The puzzle is why Marion, the eldest, is not included in Helen’s family tree. She died in Kurrachee almost exactly nine months after her wedding, suspiciously like a death in childbirth although her burial registration simply states “fever” as cause of death.[9] Our source, Helen, was only two when Marion died and, presumably, her memory of her big sister faded as the family moved on past their grief.

Welcome back to the family record to Marion Fanny, Lizzy Ann, and Constance Hayes.

Now we come to Helen’s own family group. “By marriage (3) to Emma Mary Elizabeth Bolton – as follows”. Emma was Pulteney’s fourth wife, 13 years his junior. They married in Kurrachee in 1857 and had seven children.[10] The paper lists only five children, with Helen in the middle. The youngest, listed as Emily Edith, is unknown to me. Should this be the baby whose baptism and burial records name as Grace Emmaline? She died in 1865 before she reached one year of age, of “marasmus” or inability to thrive.[11] Within four months Steward Montgomerie, a year older than Grace, also died of atrophy.[12]

Welcome back to the family record young Steward Montgomerie and wee Grace Emmaline.

Helen was three when these babies died. Perhaps all she remembered was the grief, not their names or that they were boy and girl. Or perhaps she is rolling all the missing children into one name to disguise, but still name, her loved missing sister. Because the other missing child is Edith Helena.

But she was not forgotten. There is a very different reason for her vanishing from the record.

Edith Helena Dalzell was born in January 1860, on board ship off St Helena in the south Atlantic when her parents were en route to England on leave.[13] In 1872 Pulteney and Emma retired to Jersey, where Emma died in 1878 after a lengthy illness.[14] Pulteney moved to Devon and, true to type, in 1882 married a fifth time, to Sophy Dennis, a London widow.[15] There were no children of this marriage. He died in 1887 from chronic “edema”.[16]

Of Emma’s children, the older boys Edward and William both emigrated to Australia, followed by Olivia after her father’s death. Helen went to live with her half-brother Alexander, first in Edinburgh then in Monmouthshire. After his death, she moved to London and then to the Isle of Wight.

But Edith – what happened to Edith?

In 1881 she was living at Alverdiscott in Devon with her father and her youngest sister Olivia. On 23 April 1892, aged 32, she was admitted to Bethlem Hospital in Southwark suffering from “delusional insanity with hallucinations”. Her case notes state the cause as “Family Troubles”. Two doctors’ certificates refer to her “hearing voices” and imagining people laughing at her in the street and crushing her in church.[17] It is her sister Helen whose contact details are provided and who paid the initial £10 surety for Edith’s care.

There were no further funds available from an unmarried spinster sister who was dependent on her older half-brother. On 18 November 1892, Edith was removed to The London County Asylum in Hanwell, Middlesex with her treatment chargeable to St Saviour’s Union in London, presumably because Helen lived in Barnet.[18]

On 11 July 1893 Edith moved again to the Devon County Lunatic Asylum in Exminster, Devon. The removal order was directed to the Torrington Union, which included her deceased father’s home at Alverdiscott. Edith was to remain here until she died. Her entry in the register gives her sister Helen’s contact details, this being updated many times as Helen moved with a final notation of “returned ‘not known’ May 24 1924”. Edith was buried on 14 May 1924 in the asylum cemetery.[19]

Welcome back to the family record to our sensitive Edith, whose fragile nature couldn’t cope with life as an unmarried spinster in Victorian England, and whose siblings could not support her.

[1] Ancestry.com, St Martin’s, Birmingham, England, Marriages and Banns, 1754-1937, database with images (Ancestry.com.au ; accessed 23 Jun 2023), record for Pulteney Mein Dalzell, 1833. Original data: Anglican Parish Records, Library of Birmingham, Birmingham, England, Reference Number: DRO 34/44; Archive Roll: M114.[2] Ancestry.com. Birmingham, England, Church of England Burials, 1813-1964, database with images (ancestry.com.au accessed 23 Jun 2023), entry for Pulteney Malcolm Dalzell. Anglican Parish Records. Library of Birmingham, Birmingham, England, Reference Number: DRO 35; Archive Roll: M163

[3] Findmypast, British India Office marriages – ecclesiastical returns, database with images (findmypast.com.au, accessed 23 Jun 2023), entry for Pritteney Mein Dalzell, 1838. Original data: British Library, British in India Collection, Parish register transcripts from the Presidency of Bombay, 1709-1948, archive ref: N-3-13, Folio 341, Entry 56.

[4] Findmypast, British Newspapers, “Morning Post”, “Deaths”; 21 Dec 1896, p 4 of 4.

[5] Ancestry.com. Derbyshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1932, database on-line (ancestry.com.au; accessed 23 Jun 2023). Entry for Elizabeth Davison, 1842. Original data: Derbyshire Record Office; Matlock, Derbyshire: Derbyshire Church of England Parish Registers: Diocese of Derby.

[6] Allen’s Indian Mail and Register of Intelligence for British & Foreign India, China, & All Parts of the East. United Kingdom: William H. Allen, 1850. p 458.

[7] Ancestry.com, Edinburgh, Scotland, Cemetery Registers, 1771-1935, database with images (ancestry.com.au; accessed 23 Jun 2023), entry for Constance Hayes Dalzell, 1864. Original data: City of Edinburgh Archives; Edinburgh, Scotland; Edinburgh Burial Registers; Reference: BR0014.

[8] Findmypast, British India Office Deaths & Burials, database with images (findmypast.com.au; accessed 22 Jun 2023), entry for Eliza Dalzell. Original data: British Library, British India Office Ecclesiastical Returns – Deaths & Burials, archive ref -, folio -, page 353.

[9] Findmypast, British India Office Deaths & Burials, database with images, (findmypast.com.au ; accessed 22 Apr 2023), entry for Marion Fanny Crawford, 1864. Original data: Parish register transcripts from the Presidency of Bombay, 1709-1948, :British India Office Deaths & Burials, British Library, Archive ref. N-3-38, page 224.

[10] Findmypast, British India Office marriages – ecclesiastical returns, database with images (findmypast.com.au, accessed 23 jun 2023), entry for Pritteney Mein Dalzell, 1838. Original data: British Library, British in India Collection, Parish register transcripts from the Presidency of Bombay, 1709-1948, archive ref: N-3-13, Folio 341, Entry 56.

[11] Findmypast, British India Office Deaths & Burials, database with images (findmypast.com.au; accessed 4 Jun 2019) entry for Grace Emmaline Dalzell, 1865. Original data: British Library, British in India Collection, Parish register transcripts from the Presidency of Bombay, 1709-1948, archive ref: N-3-39, folio -, page 182

[12] Findmypast, British India Office Deaths & Burials, database with images (findmypast.com.au; accessed 4 Jun 2019) entry for Montgomery Stewart Dalzell, 1865. Citing The British Library, Archive ref N-3-39, page 302

[13] Ancestry.com, 1871 England Census, database with images, (https://www.ancestry.com.au/search/collections/7619/), entry for Elizabeth H Dalzell, Alverdiscott, Devon. Original data: The National Archives (TNA): RG10; Piece: 2194; Folio: 8; Page: 11

[14] Findmypast, British Newspapers, “North Devon Journal”, “Deaths”; 23 May 1878, p 8 of 8.

[15] Ancestry.com. London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1938, database with images (ancestry.com.au, accessed 23 Jun 2023), entry for Pultency Main Dabbel, 1882. Original data: London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P89/MRY2/082

[16] General Register Office, England and Wales, Death Register, 1888, Jan-Feb-Mar, Torrington, Vol 5b, page 407, entry for Pulteney Mein Dalzell.

[17] Findmypast, ‘London, Bethlem Hospital Patient Admission Registers And Casebooks 1683-1932’, database with images (findmypast.com.au; accessed 25 Jun 2023), entry for Edith Helena Dalzell, 1892. Original data: Bethlam Hospital, ‘Admission Registers 1683-1902’, Archive ref ARA-35, Admission register, 1892-1893, p18

[18] Devon Heritage Centre, Exeter, papers for Devon County Lunatic Asylum, ‘Orders for Reception of a Pauper Lunatic’, entry for Edith Helena Dalzell.

[19] Devon Heritage Centre, Exeter; “Burial Register, Mental Hospital Cemetery”, Parish of Exminster, County Devon, year 1924, page 114, entry for Edith Helena Dalzell.

I am investigating Helen Dalzell, the authoress of Anner, A West-country Tragedy, (1895), but don’t know yet whether it coincides with Helen Lester Dalzell, though it probably could be. Do you have any trace of information about this?

Hello Almudena,

Unfortunately, I have nothing to say that Helen Lester Dalzell was or was not the author of this work. I know that in January 1895 she was living in Devon near Alverdiscott, with her father. She was only 22, so if she was the author she would have been younger than this when the article was submitted for the magazine as it was published in December 1894. Knowing the nature of her father (a strict and domineering parent) I doubt he would have permitted her to publish under her own name. However I would be very interested to learn otherwise!