From Veteran to Victim: An Unfortunate Life.

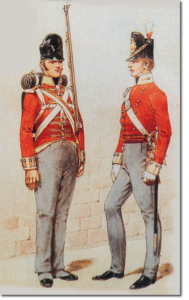

Richard Fage gripped his bayonet-tipped, flintlock musket. He crouched bravely within his battalion’s defensive square, deafened by the artillery and cannon fire of Napoleon’s troops. For hours they’d been on the edge of the battle, but the order to advance had finally arrived. Now on open flat ground, the men of the 3rd battalion of the 14th Regiment were sitting ducks. Their bright red coats and distinctive white cross straps were still unblemished by mud and blood.

Richard, like nearly half of the men in his battalion, was a teenager, the youngest recruit being 13. Normally a battalion that young would not be “considered fit to be sent on foreign service at all, much less against an enemy in the field.”

The French fired on the square. Within minutes a youngster was shot through the head, splattering his companions with blood. Another was fatally wounded, and even the shortest man in the centre of the square was injured. Richard lay flat on the ground with the rest of the regiment listening to “the hissing of balls, shells, and grapeshot, the clash of arms, the impetuous noise and shouts of the soldiery.” Feeling the thundering hooves of the enemy, he must have wondered if his short life would end there in the mud of Waterloo.

The battalion pulled back to a safer position and was posted to the outskirts of the battle, where once again defiantly held their square deterring a French cavalry regiment who “appeared inclined to charge the 14th, but were intimidated by the steady and determined bearing of the battalion.”

The following day the survivors of the victorious 3rd battalion of the 14th regiment, showing their campaign inexperience, decked in French helmets and caps, the spoils of war, marched southwards to Nivelles and on to Paris. Seasoned soldiers knew the march was hard enough without the burden of war trophies. Richard survived, and over 200 years later, a swathe of documents hint at a life that didn’t go the way he or his parents could have imagined.

A copy of a news article and a sticky note filed under “Page” in the Waterloo Veterans files held by the Genealogical Society of Queensland lead to the discovery of Richard Fage’s story and his inclusion in the Waterloo Index.

Government House Parramatta, National Library of Australia

Born about 1796 in Sandy, Bedfordshire, he joined the newly raised 14th Regiment in December 1813. For a shilling a day, he marched, guarded, and ultimately faced the French at Waterloo, later served in England and Greece, and remained with the military for another ten years. He married Sarah Brittain at Northill, Bedfordshire in 1821 and they had two sons, James and William.

Little else might have been known about him except for two events. Sometime after 1821, he tattooed “FAGE R.F.J.F.”, on his right arm at the elbow, possibly his and his eldest son’s initials. In early 1831, he and George Barlow supposedly waylaid George Richardson on the main road in Oundle, Northamptonshire, held him down and rifled his pockets, which amounted to highway robbery, a hanging offence.

Subsequently in March that year Richard and George faced two charges at the Northampton Assizes. On the first, a separate charge of theft, George was found guilty and Richard not guilty. It was alleged that after visiting a house begging for money the men stole the owner’s coat.

Prisoners’ Barracks, Hyde Park 1836, State Library of New South Wales

But Richard wasn’t as lucky with the second charge of highway robbery. The victim was uninjured and the assailants failed to find his stashed valuables, which saved Richard from the noose. However, he was sentenced to 14 years transportation, initiating a paper trail that decades later would again save his life.

Over 30 records detail his progression through the convict system in New South Wales. He departed the hulk Hardy in Portsmouth in July 1831, sailed on the Surrey, spent time on the hulk Phoenix in Sydney, and was first assigned to Bathurst. Periodically he was returned to the Hyde Park Barracks, and served time at Newcastle, Maitland, and Parramatta Goals.

Chain Gang, State Library of Tasmania

After few minor offences his sentence was extended for two years. He spent a year in fetters and chains with an Iron Gang, working on the roads out of Sydney. Finally, his Ticket of Leave in February 1847 and Certificate of Freedom completed his 16-year sentence for a crime that he said he didn’t commit. His Certificate of Freedom in May 1847 allowed him to leave Parramatta, where he worked as a gardener at Government House. Six months later, free but jobless and institutionalised, being charged as idle and disorderly, he served a further fortnight of hard labour in Newcastle Prison. He was faced with a decision, stay where he was a known criminal, or search for a new start.

Described as an old man, though only 56, he was brought before the courts in Melbourne in November 1850 and charged with being notorious murderer Archibald Macalister, who had absconded from Portland Watchhouse. Richard’s description, short and stout, with a dark complexion, missing front teeth and scars above his eyes, matched Macalister’s only in the fact that he was old. Macalister was an Irishman, and the paper noted that Fage’s accent was a noticeable Bedfordshire brogue.

AugustusG EARLE. A Government Jail Gang – Sydney N. S. Wales, 1830

Richard told the court he had walked overland from Sydney to Melbourne finding work along the way, which may have taken nearly two years. His most recent employer provided an alibi, and his transportation indent described his tattoo. “From the remarkable marks on the old man’s person no reasonable doubt could exist that the story told by him was perfectly correct.” He was discharged from the court, and a kindly stranger, moved by Fage’s story, gave him five shillings.

Astoundingly, after all this time, the documents and history support nearly all Richard Fage’s statements about his life made at the time of his arrest in 1850.

He is on the Waterloo Medal Roll and the military documents tally with his enlistment and service with the 14th regiment. The newspapers link Richard Page, Richard Fage, and his alias William Blain (Blain was his mother’s maiden name) to Waterloo and his transportation on the Surrey. The definitive link between these reports and documents is the description of his tattoo. There is no reason to doubt his story. Despite his alleged crimes, Richard Fage didn’t lie. Perhaps he was innocent after all.

1875 Enlargement from map entitled Port Hunter and its Branches (c.1819) from the Dixon Collection, State Library of NSW

There is no evidence he was ever reunited with his family, and after 1850 he dropped from the records. From a single clue he has deservedly found his way to the list of Australian Waterloo veterans, alongside governors, settlers, explorers, and other convicts. The Battle of Waterloo haunted a generation, and its veterans left an indelible if incalculable impression on the history of Australia.

Sources

https://www.napoleon-series.org/military-info/organization/Britain/Infantry/c_3-14Waterloo.html, Quotes and details of the battalion’s experience at Waterloo

https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/explore/collection/work/4408/ Depiction of a defensive square

https://www.britishempire.co.uk/forces/armyunits/britishinfantry/14thfoot1815.htm Drawing of Uniforms

Northampton Mercury, 12 March 1831

The Argus 27 Nov 1850, p. 2

The Melbourne Daily News, 25 Nov 1850, p. 2.

Port Phillip Gazette and Settler’s Journal, 26 Nov 1850, p. 2.

Records retrieved from Ancestry and FindMyPast searching Richard Fage, with a birth date around 1796, in New South Wales or Bedfordshire.

You are such a good writer Sharyn. Does Richard Fage have any living descendants?

Thanks Catherine. As far as I know, there are none from his time in Australia. I don’t know if there are any in England. His sons William and James lived to adulthood, so perhaps there are.