Gems from land files.

I have learned more about each of my grandfathers by reading their land files at Queensland State Archives. One of them, Philip Shepherd died before I was born; the other, Leopold Maxwell Skuthorp Cooper, I knew briefly as a young girl while staying at his home during holidays. Not hearing about their lives in stories passed down the generations, these files have been valuable in their revelations.

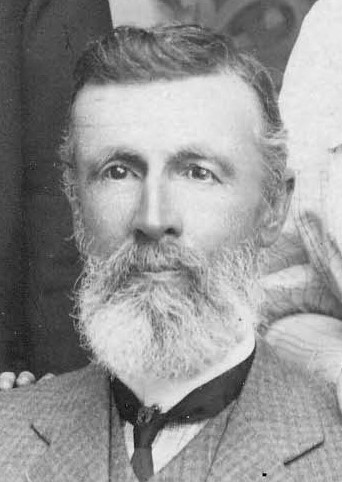

Philip Shepherd, c. 1913. Source: Personal collection

At 57 years old, Philip Shepherd, described as a retired carrier, selected a small block of 3,122 acres/1,263.5 hectares in January 1912. Called Rosewood Valley, it was close to the central western Queensland town of Jericho, so the family moved easily from their home in town when a more substantial home was completed. With the help of his adult sons when they were not busy with their wool carrying business, he spent the next two years erecting the enclosing stockproof fences, evacuating a small dam, building a hut and purchasing sheep. Hard work and considerable expense for a man in his late fifties to gain a lease for 21 years as soon as the required conditions were met.

From the file, I learn that Philip’s literacy ability was not strong as his daughter completed all the details in the extensive reports that were submitted to the Lands Department.[1] He was then generally able to sign these important documents. Philip’s acquisition of this small piece of land established a family tradition as six of his seven surviving children leased pastoral land.

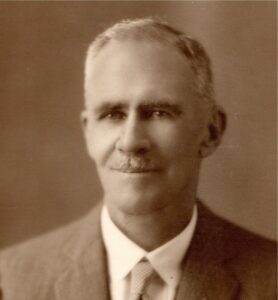

Leopold MS Cooper. Source: Personal collection.

My other grandfather, Leopold (Leo) Maxwell Skuthorp Cooper, worked as manager for his future wife on a selection, Carbean, of 9,016 acres/3,648.5 hectares on Jordan Creek south of Jericho. Bessie Pace, a governess, selected this land in March 1900. Leo acted as resident bailiff, a condition of selection, and set to work across the next two years on the other required tasks – fencing the boundary of 18 miles/29 kilometres, and building a hut – to gain the lease.[2] He added another task to his work load by applying successfully to ringbark 1,280 acres/518 hectares of timber.

This work was undertaken during the Federation Drought so there was insufficient water storage to introduce sheep or cattle. It would be another six years before the couple, married in 1904, could make a living off the land. Leo was determined that despite the drought the land would remain in their hands. Acting as attorney, he sought extensions of time from the Department to pay the rent in the early years. Information in the file suggests that he was necessarily careful with every ‘penny’ as he questioned the amount of the penalties due when back payments could finally be made.

In June 1908, the local Land Commissioner, JVS Desgrand, reported that ‘[the selector is] now, I believe, in a good financial position, he has had to struggle to make a living on the farm until the last two years’. That was the year the level of rent was due for redetermination. Leo objected to his rent being doubled to 1½d per acre so travelled to Barcaldine to present to the Land Court his case for the rent rate be set at 1d, as recommended by the Mr Desgrand. He was successful.

Leo Cooper was described by Departmental visitors as a ‘divining-rod expert’ as he demonstrated his use of the rod on his house verandah to indicate that water was present there at a moderate depth. Years later this was proved to be true through the drilling of a successful bore.

In 1913, Leo followed a similar selection process of fulfilling conditions when he gained a licence for Kurrajong, a nearby block of 13,653 acres/5,525 hectares.[3] On this occasion his dispute with the Lands Department was about the kind of netting fence he could construct as he converted the land to graze sheep in 1927. He submitted photos of the fence he believed sufficient to keep out dingoes, rather than what the Department considered necessary to protect from rabbits. There were very few rabbits, perhaps none, in this part of Queensland at the time.

He also wrote to the Department expressing his concern that the graziers upstream on Alpha Creek were not clearing the Bathurst burr from its banks, thus causing the great extent of clearing he had to do on Kurrajong. Following the Departmental inspection in 1934 he was credited for his work in keeping his land clear of burr.

While these Land Files focus on the land and its use, they reveal elements of the abilities and personalities of their owners, in these instances my grandfathers. The files, in the series called Dead Farm Files because the lease periods they covered had ended, are far from dead in what they reveal about those who lived on them.

[1] Barcaldine 3612, Dead Farm Files, Item ID ITM178492, Queensland State Archives (QSA).

[2] Barcaldine 156, Dead Farm Files, Item ITM2438913, QSA.

[3] Springsure 1921, Dead Farm Files, 3675604, QSA.

A lovely windows into the family. I had never heard of the “Federation” drought so I learnt something new.

Thanks Marg, the snippets that are not always passed down orally.