How does being a family historian change you?

By Bob McAllister

Many years ago (when I filled most of the time now devoted to family history with a full-time job), I read The Gatton Mystery by James and Desmond Gibney¹. It explored the issues surrounding a still-unsolved horrific triple murder that took place near Gatton on the evening of Boxing Day 1898².

One of the authors was a judge and his brother a senior public servant. I recall their book laid out in some detail the events as they transpired, described the background of the principals involved, made a measured criticism of the shortcomings in the investigation, and explored some of theories proposed (then and since) concerning possible perpetrators and their motives.

I remember enjoying the book over several days as I travelled by train too and from work. I have no recollection of taking issue with any of the evidence assembled or the inferences drawn from it. It was a “good” read.

Murphy family circa 1898. Ellen and Norah are standing behind their mother. Michael is not included in this photograph³.

A few weeks ago, my attention was drawn to a more recent work, Oxley-Gatton Murders: Exposing the conspiracy by Neil Raymond Bradford⁴, that dealt with the same events inter alia. This book, by a former member of the Queensland Police, promised not only to name the killer of the Murphy siblings, his motive, and previous criminal activities but also to reveal how the (so-called) police errors identified by the Gibneys were actually part of a conspiracy involving corrupt police, senior politicians and prominent churchmen intended to shield a monster from justice.

That sounded like a suitable piece of escapist holiday reading before I resumed serious research. But such was not to be the case.

Within the first page, I found myself reaching for a pencil and paper to sketch the family antecedents of a man whose name I had not known ten minutes before. Determined to accept the narrative on the author’s terms, I set my notebook aside and moved to another room to continue reading. All to no avail, within five pages I had opened an atlas, accumulated several fragments of family trees, and begun a timeline. When I put down the book to open Trove Newspapers to view the (secondary) source from which the interpretation of an earlier crime was drawn, I realised that reading this work would not be at all like my interaction with the earlier book.

I was unprepared to accept any claim that the author put forward without demanding “How do you know?”. Could this new scepticism be the result of a bias against one author while deferring to the other? Certainly, Bradford did not endear himself to me with his habit of justifying the most sweeping assertions as being “[b]ased upon 31 years’ experience as a Queensland police officer”; but my determination to accept nothing at face value could not be explained so simply.

It is apparent (as Bradford himself might boldly assert) that, in 2020, I am reading very differently to my practice in the 1980s. The breakthrough came when I recognised that I was (subconsciously) regarding Bradford’s book as a competing (indeed, contradictory) source to Gibney and was bringing to bear all the analytical tools and techniques that are used in resolving such issues in family history. In those circumstances, you cannot simply skim over the merest trifle. Every element must be questioned, including the author’s purpose in creating the work.

Eventually, I resisted the temptation to examine every aspect of the work in minute detail for long enough to finish reading. I am not convinced of Bradford’s grand unified conspiracy theory but he does raise some questions that are worthy of closer examination. The book was worth reading, even if not quite how I intended to spend my summer break.

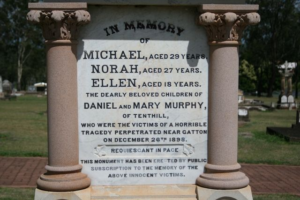

Memorial in Gatton Cemetery funded by public subscription⁵.

This experience does cause me to wonder if rather than being too cynical a reader today, I was overly naive half a lifetime ago. Should I reread Gibney today with different eyes? I am sure that The Gatton Mystery is in one of those boxes under the stairs.

On the other hand, I could simply look elsewhere for my next holiday reading. Perhaps a nice dystopian 35th-century space opera will provide a suitable diversion without that infuriating temptation to launch into exhaustive analysis and fact-checking.

Postscript:: Even worse than being a hyper-critical reader, the long-term practice of family history can lead you into wanting to “fix” the writing. A key aspect of Bradford’s thesis is to reject the popular view that Michael Murphy was the intended target of the crime and to propose that the killer actually held a grudge against his sister Honora (Norah). Were that motive to be valid, then one aspect of the mutilation of the women’s bodies may have a greater significance than at first appears. Bradford lays out all the pieces and then inexplicably fails to join the dots. Surely one more logical leap is not beyond him! Or perhaps the failure to do so reflects the social conservatism of an old copper who coyly refers to an unnatural offence (his italics) throughout the book. Now, if it were my manuscript …

References

- https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/1100519

- “Triple Tragedy” The Week (Brisbane, Qld. : 1876 – 1934) 30 December 1898: 21. <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article187459417>

- Murphy family c1898 Record number 47576, http://hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/56533,John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/6936142

- https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/88266439/norah-murphy/photo#view-photo=58262862

Hi Bob, I knew this sounded familiar. Stephanie Bennett, a Corinda resident, researched this case extensively. She published her book in 2004 and was interviewed on Australian Story. She gave a talk at my Probus Club a few years ago. It might be interesting for you to compare her results with the other two books you’ve read. Researching family history certainly teaches you to look carefully at ‘facts’. Pauline