Scrutinizing Passenger Lists: Missed anything?

How exciting it is to finally identify the ship on which our forebears sailed from Europe to start new lives in Queensland! Taking the next step by consulting the actual passenger list and sharing the voyage with an ancestor, often proves even more informative.

How many, both new dabblers or quite experienced researchers, really consider the listing and scrounge all the information available on each Queensland passenger record. Many deplore that we do not share the bountiful information which the New South Wales authorities recorded when inaugurating migration policies to the north-eastern coastline of the colony between 1848 and 1859. Their comprehensive listings, one generated by the Immigration Agent and the other by the Immigration Board, even identified the names and current whereabouts of passengers’ parents.

In the nineteenth century, migration was under individual colonial control with Queensland inaugurating procedures after Separation from New South Wales in December 1859. Late in 1860 the Crown Lands Act inaugurated an immigration programme to attract settlers. Henry Jordan, Agent for Immigration, was selected and arrived in London in April 1861. By 1867 he had been responsible for an increase in local population of 36,462 mainly from England and Wales, Scotland and Ireland. While small business owners and capitalists were regarded as ideal settlers, during Jordan’s time a variety of trades and professions were augmented from railway navvies, redundant cotton operatives, policemen, school teachers and governesses. All these names appear on the hundreds of shipping lists held at Queensland State Archives with most available on line through their website: www.archivessearch.qld.gov.au

Following one of the first rules of research: do not rely on indexes – always look at the original document if possible, consultation with the original listings nowadays can be done from home computers. While instinctively we seek the names of most relevance, once these are confirmed, we must ascertain what other valuable information we might glean from these pages.

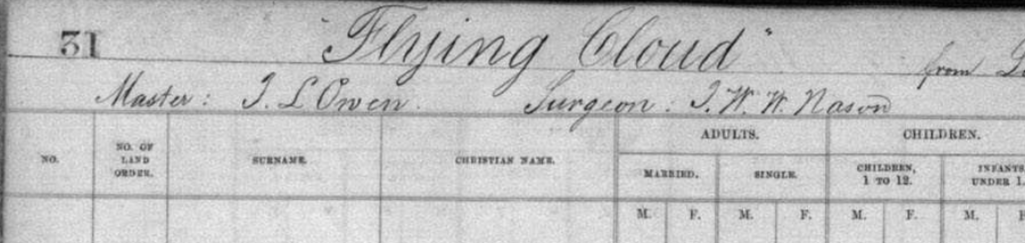

Immigration Records – Flying Cloud initial page

‘Start at the start and end at the ending’ prove enduring and valuable words of advice. The heading of the listing can indicate: the ship’s name, its tonnage, date and port of departure and the date of arrival at the final port in Queensland. Next usually appears the names of the ship’s master, the surgeon- superintendent and the matron. Various shipboard routines emphasize the importance of these people. The master was in charge of the ship and its crew, the route, access to scheduled ports, and any impositions posed by weather or maritime limitations.

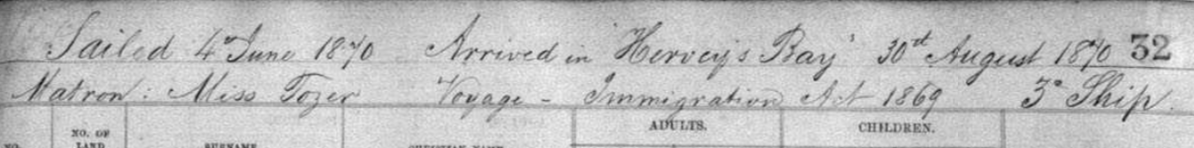

Immigration records – Flying Cloud departure and arrival details

In addition to responsibility for medical matters, the surgeon-superintendent was in charge of all passengers. With nineteenth-century voyages lasting between 60 and 190 days, consideration to keeping the passengers healthy and happy was of prime importance. He looked after their rations, water allocation and activities. From among the passengers he co-opted assistants to act as constables, school-teachers, and if he was fortunate, a travelling vicar to conduct religious services. Concerts were organized and on-board newspapers. Most valuably, as this officer was obliged to submit a report on arrival, this also should be sought from QSA.

As one of the greatest needs within the colony was for domestic servants, the safety and protection of young single girls travelling alone was of prime importance. Experience gained from convict transportation had emphasized that long voyages with adventurous young people (the majority of convicts, immigrants and crew were less than 40 years of age) led to temptations with sometimes unfortunate results. For this reason from very early in the 1860s the Queensland Government employed matrons.

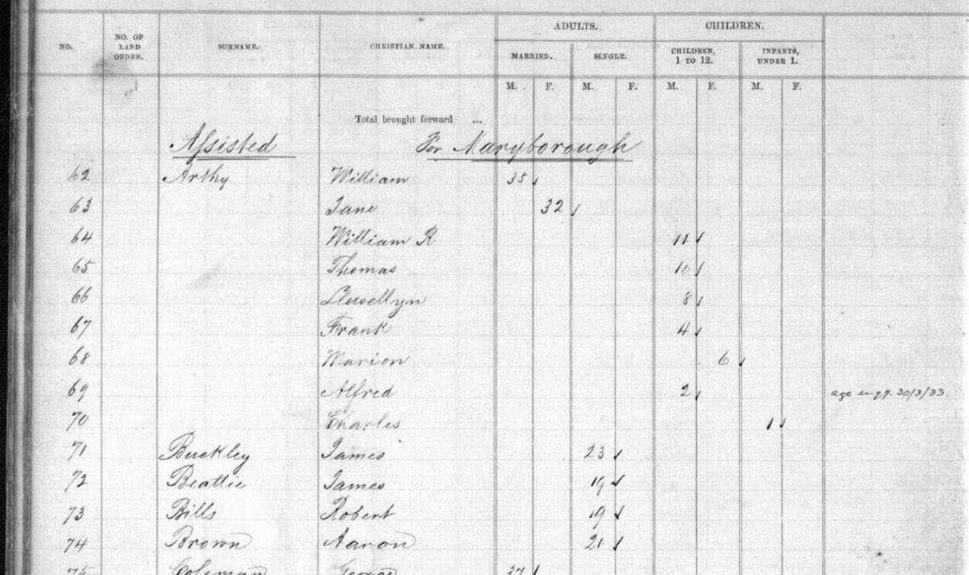

Next, seek the category in which the passenger was travelling. Full-payers were noted separately to those receiving government assistance or travelling free of charge, while remittance travellers had a relative or potential employer in the colony contributing to their fares. As the listings usually are arranged by port of disembarkation, those departing often located under each port’s name, divided by categories. The majority of lists are arranged alphabetically within groupings firstly by families, then widows (often travelling with children), single men, single girls, and occasionally, late boarders and stowaways.

Immigration records – Flying Cloud. Passenger details, category & port of disembarkation

Do ensure that all members of the one family are identified. As initially the Regulations determined that adulthood commenced at fourteen years of age (later amended to twelve years), any older sons or daughters will be listed under single men or single girls rather than within their family group. Other family connections may exist with close relatives bearing different surnames. See: Jennifer Harrison, ‘Mrs Barnfield and the Queen of the Colonies: the 1863 voyage’, Queensland History Journal, Vol. 22, No. 2, August 2013, pp. 69-80. Transcript held by GSQ at Wishart.

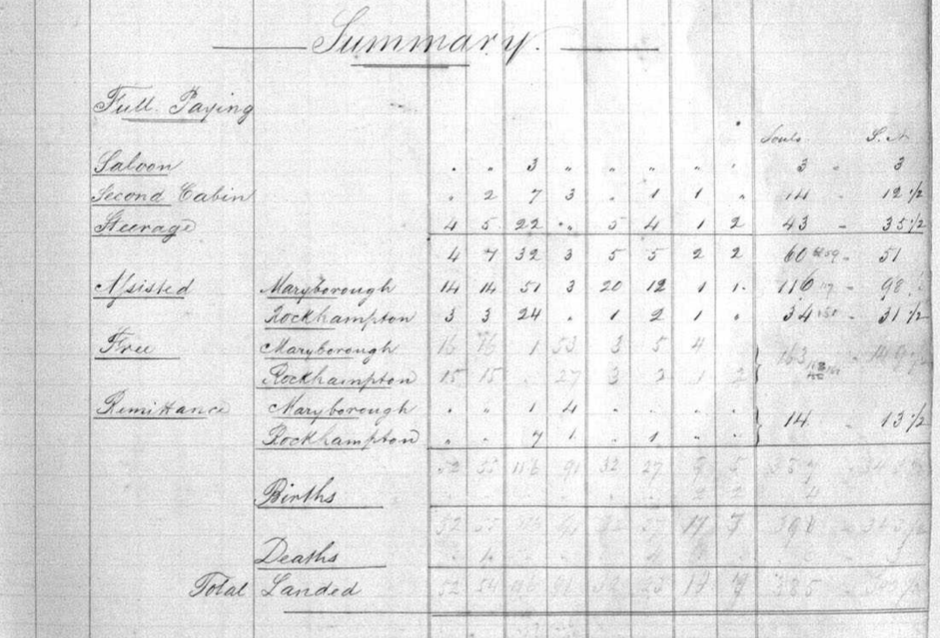

The statistical summary at the end of the listing normally gives total numbers for each gender, sometimes marital status, nationality, and births and deaths en voyage. These statistics place each voyage in context and offer further areas to investigate.

Immigration records – Flying Cloud voyage Summary

To determine the rules and regulations under which each voyage was conducted, do refer to the particular legislation covering that time period. The Votes & Proceedings of the Legislative Assembly of Queensland Parliament provide a good start. As a guide, basic information is located in Immigration Acts of 1864, 1869, 1872, 1882 and Immigration Amendment Acts of 1867, 1875, 1884 and 1886.

Queensland’s migration, dependent upon employment and political whims, remained a work-in-progress with policies constantly adjusted especially after steamships were introduced in 1881 altering routes and conditions. Recording methodology also was adapted and polished. For example, while county of origin might appear on early listings, the Agent-General officially noted and provided statistics on a county-by-county basis only for 1876 to 1879 and 1888 to 1892 inclusive. Frustratingly, occasionally only name and age might be noted. Ages, often claimed for obscure purposes, should never be assumed as accurate while widespread incidence of duplicated names attracts the usual warnings of care in correctly identifying your person. All aboard for information!

Illustrations: QSA, Digital Image no: 38458, Passenger listing for Flying Cloud, 1870 voyage. Reproduced with permission of QSA.

Comments

Scrutinizing Passenger Lists: Missed anything? — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>