So your ancestor was a jockey…

by Bob McAllister

Great Uncle Henry, known to the rest of the world as Squib Suddaby, had been a jockey. As a four-year-old, that meant nothing to me but it was apparently the explanation for why a cranky little man was always sitting in that strange crouch on a stool in the corner of my great-grandmother’s kitchen.

Half a century later, searches in the Trove newspaper archive confirmed that H J Suddaby had indeed been a jockey. His name appeared regularly in the sports pages from 1922 until the outbreak of World War II [1]. But Trove also revealed a puzzle. Just a few years earlier, the regular reports of the Bundaberg Methodist Sunday School in The Bundaberg Mail included that same H J Suddaby receiving prizes for regular attendance and Bible Study [2].

My (possibly naive) assumption was that small boys were identified as potential race riders from an early age and apprenticed to a trainer as soon as legally permissible. If the situation was not exactly the same as for Dickensian chimney sweeps, then there were (to my mind) definite parallels.

So how did a church-going late teenager from an apparently horse-free background become a participant in an industry that existed to serve gambling? All those who might have been able to offer an opinion had long passed on and I had no idea where to begin to look for answers. Although there is now a thriving sub-genre of employment-themed books in the world of family history publishing (such as My ancestor was a coal miner, Society of Genealogists); I had never seen anything that gave research advice on the world of the turf.

And then I discovered the Queensland Thoroughbred Racing History Association [3]. My first contact was through the excellent museum housed in the Old Tote building at Eagle Farm Racecourse. This historic two storey structure (which still contains much of the betting machinery from which it takes its name – the Totalisator) is crammed (quite literally) from floors to ceilings with historic photographs, jockey silks, race books, trophies, whips, and every kind of ephemera and memorabilia imaginable. Anyone with the remotest interest in racing could spend hours in that museum. But you would not find any documentary records.

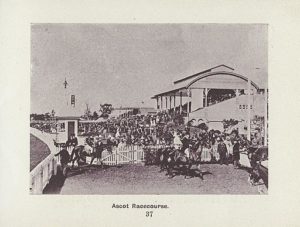

View from the saddling enclosure at Ascot_Racecourse, Brisbane 1902 StateLibQld_2_258524

For those, you must cross Nudgee Road and enter the other racecourse, Doomben. There in a corner upstairs in the public grandstand, you will find the Library which holds a collection of extra-ordinary richness. I would like to be able to provide a comprehensive review of the holdings, but, in truth, I have barely scratched the surface of one title.

The Queensland Racing Calendar [4] is a monthly publication (first produced in 1886) that documented everything that a gentleman with a horse or two (and those he employed to manage them) needed to know about racing as it was officially sanctioned in the colony. A useful rule of thumb was that if an event was not listed in the Calendar then a decent chap would not want to be associated with it (however attractive it may seem to the working class). Here you would find the schedule, prize money and conditions of forthcoming events, the names of every person licensed to work in a registered stable, the colours that would be carried by each owner’s horses, and any penalties imposed by the Club Committee or their stewards for breaches of the rules of racing.

It was from the Queensland Racing Calendar of August 1920 [5], that I learned that Henry’s entry to the world of racing was not as an apprentice jockey as I had imagined but as a licensed stable employee (also called a strapper or stable lad). He would have been mucking out stalls, feeding and perhaps exercising the horses but definitely not riding in races. He was employed in that capacity until mid-1922, by Walter (Wattie) Blacklock, a former champion rider, premier trainer and by then a revered elder statesman of the local industry.

So, what could possibly have catapulted the country boy, who had come relatively late to the industry, into the situation where he rode his first winner (for a member of not only the Queensland Parliament but also the Committee of the Queensland Turf Club) just a few months later. I was already imagining the movie with Mickey Rooney playing Squib (except that I had no idea of the plot).

Although the documents held in any repository are extremely important, an alert researcher can learn even more from the other people in the room where he or she works. When I was outlining my problem over a cup of coffee during a break, one of the volunteers said quite matter-of-factly “I would look for a death or, at the very least, a serious injury”. He went on to explain that race-riding was a very dangerous occupation in the 1920s. Falls were frequent and deaths not uncommon. Young jockeys were regarded as almost a disposable resource of the industry. When a life was lost, there was always someone else eager to take his place. My guide suggested that I find who was riding regularly for Blacklock in the first part of the year and then follow what happened to them.

So, I delved back into the Queensland Racing Calendar. Each month it listed every active apprentice jockey, the allowance he could claim and the name of his master. At the beginning of the 1920-21 season, Wattie Blacklock had two boys indentured to him. Paul Melit was obviously the more experienced having ridden enough winners in his career that he had no “allowance’ and raced against the senior riders on equal terms. Frank McCrimmon was apparently younger and still entitled to reduce his mount’s handicap weight by a full 7 pounds to offset the disadvantage of his lack of experience. During that season, Melit celebrated his 21st birthday which marked the end of his apprenticeship and his transition to being a freelance rider. McCrimmon continued to be listed as Blacklock’s only apprentice in the Calendars for August through to November 1921 but his name was missing from the December edition.

It felt somewhat ghoulish but I turned to the Register of Historic Deaths; and there was the entry for K F McCrimmon who died on 9 November 1921 [6]. The December Calendar reported that this was Queensland Cup Day attended by His Excellency the Governor, Lt Col Sir Matthew Nathan, and that the main race of the day, the Cup, was marred by a fall, three furlongs from the winning post.

Frank McCrimmon was just 14 years old when he crashed head-first into the ground amid the thundering hooves of tons of tiring horses as they neared the end of a two mile journey. His parents had been at the course to see him race and some contemporary reports claim that they reached the medical room in time for his mother to hold his hand as life expired. Although several newspapers described the condition of the horses injured in the race, few referred to the death of the rider. And yet, Henry Suddaby was indeed quick to step up to take his role as stable apprentice for the famed Ormond Lodge stable.

Unfortunately, he was not to have a glittering career as an apprentice. Rides were limited because he was simply too heavy to take full advantage of his theoretical weight allowance. Since they were unable to reduce the allocated handicap when Squib took the mount, owners and trainers preferred to select a more experienced rider. Even Wattie Blacklock regularly engaged senior riders (many of whom had been his earlier apprentices) for his better chances. By the end of his (shortened) indenture period, Henry had ridden just 12 winners on metropolitan tracks.

When Henry Suddaby’s apprenticeship officially ended, Wattie Blacklock announced his own retirement and the sale of his stable complex; giving Squib the distinction of being the very last apprentice trained by the man widely regarded as the best producer of jockeys in the (then) 60 year history of Queensland racing.

Life as a freelance jockey was to prove no easier for Henry than his time as an apprentice. Success at the major tracks continued to elude him [7] and he spent a lot of time on the country race circuit where a “city professional” could get a full book of rides against the part-time local riders. He developed a reputation for spotting bush horses that Brisbane trainers could buy on the quiet and bring into town without fanfare for a betting coup.

However, he was obviously well respected by his peers. All riders paid a few pence from each of the riding fees into the Distressed Jockeys Fund. For many years, Henry was re-elected as Treasurer for that fund [8], in which role he handled payments for the medical expenses of colleagues who survived a race fall and to the widows and children of those who did not. I wonder how often he thought about little Frankie as he undertook those duties.

By the time I met Great Uncle Henry in the mid-1950s, his occupation was listed in the Electoral Roll as Casual Labourer. His riding career was long past and yet he obviously felt the ongoing effects of the occupational hazards of race riding. I can only imagine that a weekly visit from the noisy and precocious child of his mother’s favourite granddaughter was the last thing that a middle-aged, unemployed man in chronic pain looked forward to. Retreating to his stool in the corner of the kitchen was an entirely rational response to my arrival.

And it did cause me to ask the question that produced the response “Great Uncle Henry had been a jockey”. Just imagine what I might have missed finding out if I had not!

Sources

[1] “Saturday’s Racing”, Daily Standard (Brisbane, Qld: 1912 – 1936) 4 December 1922: 7 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18241647>

[2] “Methodist Sunday School” The Bundaberg Mail (Qld: 1917 – 1925) 24 April 1918: 4. <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article216444850>

[3] http://thoroughbredracinghistoryassoc.org.au/

[4] https://trove.nla.gov.au/version/22506442

[5] “Registered Stable Employees,” (Brisbane) The Queensland Racing Calendar, 36 (5), p. 75.

[6] Registrar-General, Queensland Death Registration 1921/B35719

[7] “Jockey W. Hill Rides Fifty-One Winners” The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld: 1872 – 1947) 30 July 1936: 21 (City Final Last Minute News). <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article181913600>.

[8] “Malt Pie Well Backed For To-day” The Courier-Mail (Brisbane, Qld: 1933 – 1954) 22 February 1936: 9. <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36787362>.

This is one of those wonderful research stories about occupations and where to find the records – thanks Bob!

What a terrific story, Bob. I’m constantly amazed at the wide variety of experiences that our ancestors had; there are a wealth of resources out there if we only ask the right questions and find out where to look. Pauline

Thanks Bob. I have relatives with a horse racing past and I now know where to find the record! Sue

Thanks Bob for bringing to life a wonderful story. What a treasure trove that resource must be.

Thanks for a really interesting story, Bob. My grandfather was ‘into’ racing about that time and had a horse named Lobba Minnie. It did win a couple of races but was no Phar Lap. I wonder if he ever met your Great Uncle Henry?

My father was a jockey in the 1950s or 40s

John Vincent Robarts he lived in Brisbane, just would like information for my grandchildren any information would be so appreciated.

Thanks for your comment Jo-ann. Unfortunately Bob McAllister, the Blogger who wrote this article has passed away since writing the story. One of your options for finding out more would be to look through Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/) searching on either jockey or his surname, but maybe try different ways of spelling the surname in case the reporter spelt it incorrectly. You could also look through the two individual racecourse names of the period. Also maybe search through the State Library of Queensland’s catalogue for jockeys.

Does anyone remember a jockey named Neville Edward Seipel? I believe he was a jockey, also he trained a winner of The Brisbane Cup.