The Gift of a Name.

A collection of historic photographs landed in my email months ago. One photo caught my eye – a woman and four small children sitting next to a sign advertising the children for sale.

The mother hides her face in shame after putting her four children up for sale.

With a bit of digging I learned that the photo was published by an Indiana newspaper 5 August 1948, with a caption suggesting that the woman’s husband was out of work, the family had no money for food or rent and had decided to sell their children.[1]

Similar circumstances overtook my grandparents a decade earlier. My grandfather lost his minimum-wage job as a truck driver during the Great Depression; unable to meet the mortgage payments on their modest home, he decided to put the property on the rental market and move the family to less costly accommodation. Grandad calculated that the rental income would be sufficient to pay both the mortgage and the cost of renting another place for his family; however the calculation failed because the only affordable accommodation he could find was a garage barely large enough for two adults let alone four children. He chose what he considered the least disagreeable alternative – he found live-in positions as housekeepers for his teenage daughters. My mother and her closest sibling would be abandoned, if only temporarily, when they were ‘farmed out’ – the phrase my mother used for the upheaval in her life that forced her into what can only be termed involuntary servitude, separating her from her parents and closest sibling.

The woman in the photograph divorced, remarried and had four more daughters; her abandoned children, having endured years of ill-treatment, physical and emotional hardship in a series of foster homes, eventually attempted to reunite with their birth mother but sensed little in the way of sympathy or understanding, let alone explanation or apology.

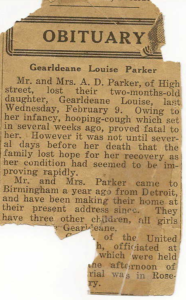

My grandparents eventually reclaimed their home and re-united their family but, as I documented my family history, I learned that my mother may have experienced the death of an infant sister. My brother had sent an image of a tattered newspaper obituary found in a trunk full of photographs and other family memorabilia: “Gearldeane Louise Parker, two-month-old daughter of Mr & Mrs A.D. Parker” (unmistakeably my grandparents). I tried and failed to identify the newspaper, but the name Gearldeane (a typo?) and references to Birmingham and Detroit were too coincidental to dismiss.

Tattered obituary for Geraldine Louise Parker

As far as I was aware, Mum’s sisters were all very much alive. The obituary gave the day (Wednesday) and date (February 9) but not the year of death which, according to an on-line calendar, could only be 1918 or 1921. Documenting the child missing from all family records took several years. The discovery of a death certificate for Geraldine Elizabeth Parker b. 8 December 1920, d. 9 Feb 1921 confirmed her parents as my grandparents, Acie and Mary Louise Parker.[2] She died of whooping cough and malnutrition (too weakened to suckle; the possibility that she fell victim to the influenza pandemic of 1918-1921 cannot be ruled out). The confusion over her middle name is resolved (for me at least) by the fact that my grandmother’s middle name is Louise; the informant for the death certificate was my grandfather who, I assume, mistakenly gave his deceased daughter’s middle name as Elizabeth (my great-grandmother’s name). A clue to Geraldine’s burial place at the end of the obituary (Rose—-ry) turned out to be Roseland Park Cemetery, confirmed when my cousin viewed the burial record at the cemetery in Birmingham, Michigan. Geraldine Louise is buried in a pine box, in an unmarked grave, which can only signify impoverishment: my grandparents were unable to afford better, which in turn explains Geraldine’s disappearance from the family record: early death and anonymous burial were shameful, somehow suggestive of neglect and impropriety.

The sudden disappearance of this child must surely have disrupted the lives of her siblings and laid a pall of grief on the family. The birth of another child in January 1922 may have eased the pain of loss for her siblings, but equally may have confused and unsettled my mother and aunt (4 and 5 years old at the time). Another shock awaited the two of them when the Depression forced their impoverished parents to move to the other side of the city, leaving Mum and her sister to live with strangers, working all day, every day, for room and board, unable to afford even a streetcar ride to visit their parents. The physical separation and emotional deprivation must have seemed endless.

I understood early on, from overheard conversations between my mother and aunt, that loss and separation engendered a strong work ethic and determination ‘never to go without’, which explained for me the kitchen drawer stuffed with odds and ends – rubber bands, bits of string, used envelopes, tinfoil, tacks, screws, paperclips, coupons cut from the newspaper to be redeemed at the grocer for pennies off the price of whatever we needed to buy. I formulated the notion that my mother had a saving bone (one more bone than anyone else on Earth) preventing her from discarding anything that might conceivably be useful; I teased her about it, and her saving bone became part of the family lore.

Because I know how my mother’s life unfolded, it is clear that earning her keep at a tender age strengthened her resolve to work hard, complete her education and find satisfying well-paid work. She finished high school in the evenings, studied bookkeeping, shorthand and typing at commercial college, found employment and assisted her parents in paying the mortgage on their home. She met and married my father, and together they provided their children with a safe and secure home, good nutrition, a good education and an appreciation for books and music.

And my mother gave her first-born the name of the baby sister who died when Mum was barely five years old. She never told me I had been named after Geraldine Louise, perhaps sensing that this knowledge might burden me with an obligation to live as a replacement or surrogate. She gifted me the name to honour the memory of her sister and may have intended to tell me some day, but the onset of early dementia made that plan moot. Mum died two years before I learned that Geraldine Louise’s life ended almost before it began.

[1] The Vidette-Messenger, Valparaiso, Indiana, https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/4-children-sale-1948/

[2] Michigan Department of Community Health, Division for Vital Records and Health Statistics; Lansing, Michigan; Death Records. Source information: Ancestry.com. Michigan, Death Records, 1867-1952 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015.

Geraldine, your story was so sad to read but at the same time gives us a good understanding of the sacrifices families had to made during the time of the Great Depression. I have heard tales of how it affected my own ancestors here in Australia, but times were obviously much harder in your homeland of Michigan. Thank you for sharing your story.

Hi Geraldine, what a sad story, but told with your usual skill. The situation faced by your mother and aunt was probably replicated many times, but that doesn’t make it easier to bear. It sounds as if your mum was determined to give her children a better life. Thank you for sharing.

A wonderful insight in the harsh times that many of our parents experienced no matter where they were in the world. Hard working parents just wanting to keep a roof over their heads and food on the table for everyone. As you mentioned it was the eldest children that often suffered the most. My Mum was made to leave school at age 13 and go to work, until the place found out her age, but Grandfather could not send her back to school as he could not pay for the uniform or books etc. My mother always regretting not getting her full education, but she also had a “Saving bone” and in that one drawer in the kitchen you could find anything you were looking for. Hard work and a need for security has always dogged my mother. So thank you for writing this, brings back memories of what my own parents had to endure during the hard times.

A tragic story beautifully told. No wonder your mother was so determined to improve her life, and save. We stand on the backs of our ancestors’ hard work and achievements.