The Sinking of the Sovereign: a family tragedy

‘Mary, there is no hope for us now; we shall go to heaven together.’ These were the last words Robert Gore spoke to his wife, Mary, before they and their two young children drowned when the Sovereign, the steamer on which they were travelling to Sydney, sank off Stradbroke Island in March 1847.

Robert Gore was my great, great uncle and he and his wife, Mary, and two brothers and his widowed mother arrived in Sydney from Ireland on the Fairlie on 8 November 1841. Three months later Robert was admitted as a barrister of the Supreme Court of NSW. Their three children were born in Sydney: their daughter Leonice Souvoroff on 17 January 1842 and their two sons, Strafford Robert on 3 July 1843 and St George Baldock on 4 April 1845.[1]

Robert’s two other brothers, Ralph and St George Gore, had arrived in Sydney in early 1840 but by the time Robert landed, they had left for the Darling Downs where they settled on land at Grass Tree Creek, later called Yandilla. These lands had been inhabited by Aboriginal peoples for thousands of years and the Gores settling on their land would have dislocated their way of life and had a profound effect on their customs and traditions.

Robert and his family must have decided to join them sometime after the birth of their youngest son because by March 1847, the couple and their two sons (they probably left their daughter with other members of the family at Yandilla) decided to travel from Brisbane to Sydney on the steamer, the Sovereign.

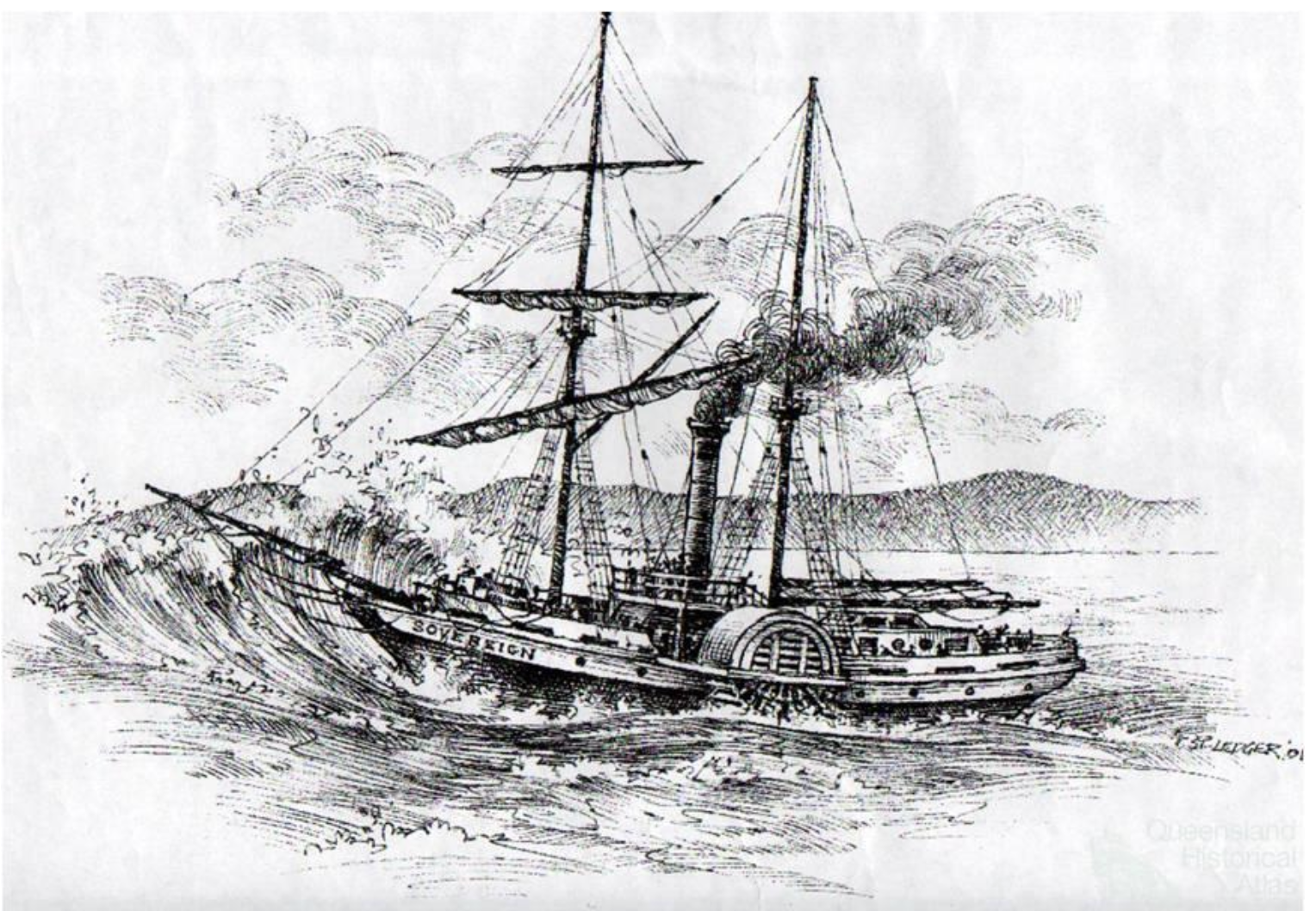

Sketch of The Sovereign by C.St Ledger, courtesy of North Stradbroke Island Historical Museum collection.

By 1837 steam ships which used sail power and steam driven paddle wheels, began operating along the east coast of Australia. The Sovereign, a paddle steamer of 119 tons, was built at Pyrmont, Sydney in 1841 and used firstly on the Hunter River run which was operated by the Hunter River Steam Navigation Company. In February 1843, the Sovereign was reassigned to the steamer service between Moreton Bay and Sydney.

On 3 March 1847, the Sovereign left the port of Brisbane bound for Sydney with 54 people on board (passengers and crew). The captain took the southern route, between Moreton and North Stradbroke Islands rather than the safer route north of Moreton island. A succession of gale force winds delayed the ship at Amity Point until 10 March when Captain Cape made an attempt to cross the bar but had to turn the ship back. The next day he made another attempt and crossed the first ocean swell and as the ship passed over the second roller, The Moreton Bay Courier reported that Mr Gore was heard to say. ‘Here is a five-barred gate – how nobly she tops it!’

However, soon after the ship was in trouble. The engineer called to Captain Cape that the framing around the engines had started to split and part of the machinery had broken down. The vessel drifted and although there was no wind, she continued to drag towards land with the waves crashing on the ship. The wool and wood stored on the decks lurched dangerously with three men being killed and two others braking limbs.

A Mr Stubbs who survived the disaster reported that water then started flowing onto the ship. He tried to give some assistance to the women and children who were sheltering in the ladies’ cabin and found some spirits which he gave to Mrs Gore and the other women. He and Mr Gore tried to block the water flowing into the cabin but were not able to. At this point, Mr Stubbs reported that Mr Gore said to his wife, ‘Mary, there is no hope for us now; we shall go to heaven together.’ Mrs Gore then repeated several times, ‘We can die but once. Jesus died for us. God keep us.’ The Gore family were devout Anglicans.

They then all went onto the deck and Mr Stubbs, seeing that the ship was about to sink, called out ‘Avoid the suction’ and jumped overboard with many passengers following. When he was in the water, he saw Mrs Gore floating with her face upwards and believed she had died from fright. One of her sons was nearby and Mr Gore was about 30 years away and cried out, ‘For God’s sake bring me my child.’ Mr Stubbs was able take the child to his father and the last he saw was Mr Gore clinging to the skylight with the child in his arms.

Mary Gore final resting place at Toowong Cemetery, Brisbane.

Mr Stubbs eventually made it to the shore at Amity Point on Stradbroke Island as did nine other survivors owing to the efforts of a group of Aboriginal men from Quandamooka (Moreton Bay) who put their own lives at risk in extremely dangerous conditions to swim out to the wreck and pull the survivors back to shore. Mary Gore’s body and that of her son, Strafford, who was three years old, were washed up on the shore at Moreton Island. They were buried there until relatives and friends brought their bodies to Brisbane and they were placed in the Church of England Cemetery at Paddington. The bodies were subsequently moved to the Toowong Cemetery when the Paddington Cemetery closed in the early 1900s.

A memorial tablet to the Gore family lost on the Sovereign was placed in St John’s Pro-Cathedral sometime after it was erected in 1854 in Queens Park, Brisbane. This tablet was moved to St John’s Cathedral when the previous cathedral was pulled down.

There was an immediate investigation into the disaster. The Moreton Bay Courier reported that the ’most competent people who have examined the wreck’, concluded that the vessel was not sufficiently seaworthy for a voyage to Sydney. The timbers of the vessel were defective. There were also questions about the engines which had been taken from the King William IVth, a ship which had been built for river navigation not for an arduous ocean voyage, and they were not fitted properly as their casing was the first to give way.

Questions were also asked about the amount of cargo the vessel had on board. It had been carrying 140 wool bales, 40 of which were stowed on the deck and their dislodgement directly caused some deaths. There was also a large quantity of wood and coal on board which made the ship sit low in the water. It appeared overloading ships was the practice of the Hunter River Steam Navigation Company who owned the Sovereign. There were also questions about the use of the southern route between Moreton and North Stradbroke Islands which was a shorter route but, with its surf and shoals, was not the safest route.

The Hunter River Steam Navigation Company did not accept blame and immediately sacked Captain Cape who had survived the disaster. However, the surviving passengers commended Captain Cape and the crew for the way they handled the situation stating that, ‘… you did everything that man could do to save the lives of all on board, as well as to provide for the safety of the vessel.’

This must have been terrible blow for the extended Gore family. They would have gathered around the only surviving member, little five-year-old Leonice Souvoroff Gore. She had preceded her parents to Sydney so perhaps the family was relocating to Sydney. Did they read the graphic descriptions in the press of their deaths or the poem written by a poet, self-styled as Malwyn, for the Port Phillip Herald in Victoria which appears to draw on the eye witness account of the last moments or Robert and Mary Gore.

There was a shriek; yet two

Stood calm amid that crew;

A husband and a wife

They had been linked in life

By ties of holier kind

Than those the many bind;

And now in death’s dark hour,

They felt Religion’s power:

No more of storms for them,

Of Earth’s unquiet weather –

The waves’ roar was their requiem,

They’ve gone to Heav’n together![2]

Bibliography:

Cumbrae-Stewart, F. W. S., ‘Notes on the Registers and Memorials at St. John’s Cathedral, Brisbane.’ Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol. 1, Issue 1: pp. 25-42. https://www.textqueensland.com.au/item/article/eb7027f7283907f5f7f67e16c348fcf4

Friends of Toowong Cemetery, One Year 1923. https://www.fotc.au/stories/1923/

The Moreton Bay Courier. (1847, March 13). The Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), p. 2. Retrieved April 30, 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3714205

The Moreton Bay Courier. (1847, March 20). The Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), p. 2. Retrieved April 30, 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3711440

The Australian, (1847, March 27). Total Destruction of the Steamer ‘Sovereign’, p. 1 (Supplement to “The Australian Journal.”). Retrieved April 30, 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article37129084

Footnote references:

[1] Shipping Intelligence. (1841, November 8). The Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser (NSW : 1838 – 1841), p. 3. Retrieved April 30, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32191313 SUPREME COURT. (1842, February 16). The Colonial Observer (Sydney, NSW : 1841 – 1844), p. 4. Retrieved April 30, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article226359820

[2] The Moreton Bay Courier. (1847, May 15). The Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), p. 4. Retrieved April 29, 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page540658

You write so well, Sue. Sadly they had no choice in their fate, but they were so brave in the face of death and the poor children. Great research into coastal shipping, a topic that is of interest to many of us. A coloured portrait of the Sovereign is held at the Qld Maritine Museum and can be viewed on their facebook page.

What a terrible tragedy! They were doomed weren’t they? Thankfully today’s maritime standards are much better and events such as this tragedy, resulted in improved regulations. Your story makes you appreciate the great risks and dangers our migrating ancestors faced. Thanks for sharing it Sue.

Thank you for your kind comments. I was quite shocked how explicit the description of their last moments was as told by the eyewitness and reported in the newspapers at the time. It must have been tragic for family members to read this.

A great story brought to life in such detail. It’s amazing how much information was recorded in the early newspaper articles.