Travels with Smithy’s Aunt.

Two million residents of Buenos Aries woke up on the cool Saturday morning of 6 September 1930 expecting to enjoy the weekend; stroll in the parks, hit the shops or hop on a tram to the beach. Early on it was plain this day was different. Aircraft buzzed overhead and the shoppers were soon outnumbered by armed protesters, as the squares and streets filled with angry mobs. The city dubbed the “Paris of South America” was about to be consumed by a military coup, and young Australian, Dorothy Kingsford, was a crucial witness. Sudden rigid censorship of news outlets, telephone calls and cablegrams silenced critics.

Inside the safe walls of the luxurious Palace Bosch, residence of the American Ambassador, Robert Woods Bliss and his wife Mildred, incoming intelligence was translated and compiled into urgent messages to Washington.[1] Dorothy, Mildred’s private secretary, fluent in French and Spanish, and with extraordinary shorthand skills in three languages was a vital link.

Dorothy Kingsford’s story has been lying quietly in my files, with tantalising details hinting at many ocean voyages and a long secretarial career in influential places. With subsequent discoveries I have criss-crossed the world from Sydney, through the giddy years of Paris in the 1920s, to 1930 revolutionary Argentina, the social whirl of diplomatic Washington DC, and the intrigue of a war-time British Embassy. She has left a trail through shipping records, UK and US Census documents, newspapers on three continents, and private correspondence files. For a single woman who lived through two wars and a depression it was a dizzying life.

Dorothy Kingsford, born in Launceston in 1892, was the youngest daughter of Richard Ash Kingsford, a well-known Queensland identity, and his second wife Emma Jane Dexter. When he married 23-year-old Emma, Richard was 70 and his three children by first wife Sarah were grown up, the youngest being 32 years older than Dorothy. In 1897 the eldest daughter Catherine gave birth to Charles, or Sir Charles Kingsford Smith as we know him, making Dorothy ‘Smithy’s’ Aunt.

Richard Ash Kingsford died in Cairns in 1902 when Dorothy was nine, leaving them comfortably well of, enabling Emma to secure Dorothy a broad and useful education which set her on a path to global adventure.[2] First stop was Toowoomba and the new Spreydon Girls School, established in 1908, providing classes in dancing, art, writing, and Dorothy’s favourite, French.[3] She was a gifted student completing her schooling in 1909 as Dux of the College, qualifying for a university placement in Sydney, but Emma’s determination to find her the very best education meant going overseas. Next stop, Cheltenham Ladies College, today the most renown girl’s school in England. Established in 1853, Cheltenham thrived under head mistress and suffragist Dorothy Beale, who introduced science and maths to the curriculum. In addition to “finishing” her education and improving her language fluency, Dorothy made important friends.

The outbreak of war in August 1914 brought Dorothy and her mother back to Toowoomba, but when Belgian musician Henri Verbrugghen arrived in Sydney in 1916 to start a music school and orchestra, Dorothy was among his first students enrolling for a three-year course.[4]

The war finally over, and a new decade dawning, the 1920s promised a new era of freedom and opportunities for women, especially for those with a well-rounded extensive education. At 28 with no husband in sight, Dorothy was free to enjoy the giddying prospects waiting on the other side of the world. She and Emma arrived in Paris to a world awakening from the long dark war years. As they strolled the cafes of Montparnasse, they may have sipped coffee with F Scott Fitzgerald or Ernest Hemingway. At Montmartre, exhibitions by Marc Chagall and Picasso attracted crowds. In the theatres and dance halls, the new American music craze, Jazz, electrified the dancers, producing the likes of Josephine Baker and the frenetic Charleston.[5] Although surrounded by the frivolous action of Paris’s “Annees Folles” or crazy years, Dorothy learnt French shorthand, adapting it to English and later to Spanish.

Her prodigious talents can’t have gone unnoticed. If she was employed during that time, its nature is unknown but in 1927, Americans Robert Woods Bliss and wife Mildred, on the eve of their diplomatic posting to Argentina, hired Dorothy as their private secretary.[6] Her language skills, shorthand and writing talents, appreciation of music and enjoyment of travelling presented the perfect candidate.

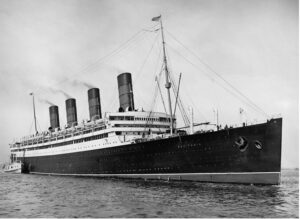

Together with her mother, 59-year-old Emma, she embarked on one of her many Atlantic sea crossings, via New York, to Buenos Aries, and a long and close relationship with Mr & Mrs Bliss. A career diplomat serving in US Embassies in Venice, St Petersburg, Brussels, Paris, Washington and Buenos Aries, Robert Bliss, together with his wife Mildred specialised in collecting Byzantine and Pre-Columbia artworks. Their home, Dumbarton Oaks in Washington DC, became a museum and research institute.[7] Correspondence from the Dumbarton Oaks archives reveals Dorothy’s close relationship with Mildred, assisting in all aspects of the Bliss’s lives from their diplomatic responsibilities and art collection purchases to their acquisition of rare plants for the Dumbarton Oaks garden.

Although only returning to Australia once, in 1936 shortly after Sir Charles Kingsford Smith disappeared over the Andaman Sea, Dorothy criss-crossed the Atlantic, visiting England on her holidays, and in 1933, about six months after her mother’s death in September 1932, returned to England with Emma Kingsford’s ashes.

In 1940, Dumbarton Oaks was given to Harvard University and Dorothy went to work for the British Embassy in Washington. Throughout the war she had responsibility for censorship and negotiating US exports through British blockades. After the war she reorganised the embassy library and wrote weekly reports to the British Foreign Office.

During her time in Washington, she was deeply involved in the Daughters of the British Empire. Founded in 1909, the American society consists of women with British or Commonwealth birth or ancestry. Dorothy, a program chairman for the Queen Elizabeth Chapter organised guest speakers and charity events.

One popular get-together was a billy tea. Women from Australia and New Zealand formed themselves into the Billy Tea Club. Described as something like an American picnic, the difference being that tea was boiled in a billy or kettle over an open fire whereas Americans did the same for picnic coffee.

Dorothy returned to Australia in 1950, after 25 years abroad, warmly greeted by the Australian American Association Women’s group in Melbourne. She died in Melbourne in August 1952.

While her famous nephew pushed the boundaries of ocean crossing from the air, Dorothy pursued an independent, globe-trotting life, traversing the world by ship, leaving a paper trail of records. Set against a backdrop of revolutions, two wars, a depression and US diplomacy, the documents reveal a fascinating life.

Additional References

1911 UK, 1940 US Census, and Immigration and shipping records located in Ancestry.

US newspapers from FindMyPast

[1] Residence of American ambassador Bueno Aires https://buenosairestogo.com/things-to-do/a-e3b07ba4-8f63-4fdc-ae5a-3f363ae06b84

[2] Robert Ash Kingsford Death Certificate from Unrelated Certificates GSQ

[3] Spreydon Girls School. Now Fairholme College at different location. Spreydon still exists at 30 Rome St, Newtown.

[4] Henri Verbrugghen https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/verbrugghen-henri-adrien-marie-8913

[5] fast and energetic in a rather wild and uncontrolled way

[6] Robert Woods Bliss https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/annotations/robert-woods-bliss

[7] Dumbarton Oaks, https://www.doaks.org/

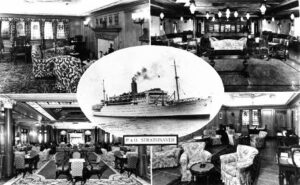

A fascinating story Sharyn. what an amazing and independent life for the times. My connection to the Aquitania is the ship that brought my Dad home from WW2. I don’t imagine the dining room was anything like your photo.

How amazing Rosemary, the ship would have held a special place in your father’s mind.