“OURS WERE THE HEARTS TO DARE”

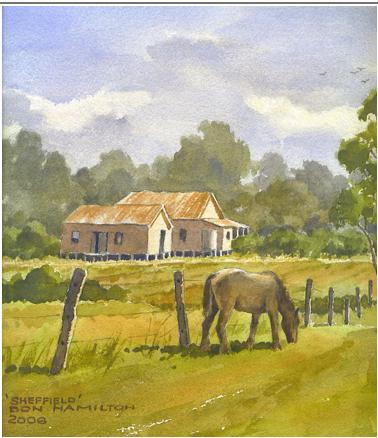

“Sheffield” Homestead from a watercolour by Elizabeth Smith’s great grandson, Queensland artist, Don Hamilton

I never cease to be amazed at the fortitude and endurance of the pioneer women of our country. Often their story is unsung, as they just went about their daily lives unaware of their spectacular contribution to the future of this nation, but simply doing their best, dealing with the strangeness of this new land and confronting head on the harsh realities of life. They coped with deaths of children, droughts and disasters, and sometimes the destruction of all they had worked for, with no option but to start again.

When Elizabeth Yates aged 17 years, daughter of a Derbyshire quarryman, married Henry Smith in Sheffield in 1852, she was already well acquainted with poverty and hard work. Nine years later, having lost two baby girls in infancy, but with young Robert aged eight and two-year old Sarah Ann, she and Henry set sail on board the Saldanha towards an unknown future.

Their arrival at Brisbane in January 1862 in a terrifying south-east gale was followed eventually by an unceremonious offloading at night into a dirty, inhospitable Kangaroo Point wharf shed.[2] Undeterred, the Smiths made their way to Maryborough, an area praised by Henry Jordan in his popular 1861 lecture tour of England as offering fertile productive farming land.[3] After their arrival however, they struggled to exist, living for over two years in a tent city in Lennox Street near to where St Paul’s Church of England now stands.[4]

It was a life of great hardship. There was joy when their second son Weston was born on 22 March 1862 soon after their arrival, but grief was close behind when Sarah Ann, after surviving the rigours of their voyage out, died 5 days later aged only two years and ten months. Two years later twins, Jane and Henry were born at Lennox Street but both died within a month of diphtheria. In December 1865 another boy, Henry Charles was born and survived.

1866 was a year of financial crisis for Queensland, and there was wide scale unemployment.[5] Fortunately, the discovery of gold at Gympie in 1867 helped rescue the situation. Many unemployed converged on the town, including the Henry Smiths with Elizabeth recorded as being one of the first women on the Gympie goldfields and much sought after as a midwife.[6]

“Granny” Elizabeth Smith

During their two years on the goldfields, Henry acquired some wealth, probably more through his Yorkshire gift of wheeling and dealing than by finding gold. Elizabeth was sad, dispirited, homesick and pregnant once again, so it was decided that they would return to England to see their families.[7] On the 10th of February 1868 they sailed for London together with their three surviving children, Robert, Weston and Henry Charles. It had always been family folk lore, but unproven, that my grandmother, Mary Edith Smith, born on 27 April 1868 and officially recorded as “born at sea” had been named after the ship which took them home. A fortuitous find in Trove has proved this correct. They sailed on the barque Mary and Edith. [8]

Henry and his family stayed in England for about six months. They found the Old Country cold, wet and generally miserable and they missed the Queensland sun, so again they farewelled family and made the return voyage to Australia arriving in Brisbane on the 25 January 1869.[9]

Soon after the Smiths’ arrival back in Maryborough, Henry became aware of land being offered to settlers under the “Homestead Scheme” and made application to take up pastoral land on the Burrum River.[10] After being accepted and paying the requisite deposits, the family sailed from Maryborough on a trading boat to their selection on the north bank where they were put ashore with only an oilskin to provide shelter until Henry could cut the timber to make a slab hut.[11]

Henry continued to work in Maryborough, rowing across the river in a dinghy then walking the eighteen miles into town, returning at the weekend bearing the provisions.[12] His absence meant that Elizabeth and the young children were left on their own in a small slab hut surrounded by dense scrub, with no close neighbours. The indigenous peoples were very numerous in the area and on occasions raided huts and stole blankets and food.[13] Probably as a result of mistreatment by some of the early farmers and miners, this situation took a turn for the worse and the aboriginal population in this area was later described as “more dangerous… than any other settled district of the colony”.[14] Henry and Elizabeth’s home was “completely ransacked” in 1873.[15]

However, the indigenous people were not the only challenges for the new settlers. In March 1870, soon after the family had taken up their selection the “big flood” occurred. Days of continuous rain made the gullies and creeks of the Burrum rush down with tremendous force. Henry’s land was inundated together with that of his neighbour Mr Whitley and the two families including six or seven children, barely managed to escape with their lives. For two days and nights they huddled together, wet and hungry, under a sheet or two of bark. My grandmother, Mary Edith was under two years old at the time, and her young brothers were aged five and eight. The Smith family all survived but the seven weeks old Whitley baby died of exposure.[16]

In January of 1871, Elizabeth gave birth to probably the first white child to be born on the Burrum. Tragically this little girl, also named Elizabeth, died at the age of 14 months from “convulsions”. Grief and loss were constant companions for pioneer parents. However, in August 1873 a son Thomas was born and survived. Such was the spread of Elizabeth’s family that her eldest son Robert aged 22, was married in 1875 two years after Tom was born. In all Elizabeth gave birth to eleven children, six of whom, including one set of twins, died in infancy.

Shortly after the Smiths had arrived at their selection, their young sons Harry and Weston made themselves a garden near the house planting amongst other things, some orange seeds. These grew and flourished, providing inspiration for Henry. Within a few years he had developed the successful enterprise known as the Sheffield Orangery, with cases of citrus seedlings shipped down river by steamer to places as far distant as Melbourne and Darwin.[17] The oranges and mandarins also became a good source of revenue and by 1897, Henry was sending 100 to 250 cases of fruit a week to Melbourne.

Five Generations – Granny Smith (left) with daughter, granddaughter, G. granddaughter and G.G. Granddaughter.

Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947) 14 June 1930: p8

To Elizabeth, however, goes the honour of introducing the famous Ellendale mandarin to the Burrum region. She requested Captain Matthew Walker who traded up and down the Queensland coast, to bring her some mandarin seedlings from an orchard north of Bundaberg and she later shared these with a neighbouring orchardist, Mr E.A. Burgess.[18] Around 1878, one of these seedlings bore a new fruit variety subsequently named “Ellendale Beauty” after the Burgess Ellendale orchard.[19]

The years rolled on for the Smith family with all their attendant joys and sorrows. There were marriages, births of grandchildren, losses of loved family members and the inevitable issues that famers have always faced of bad seasons, poor prices, droughts and floods. Henry himself died in 1903, and Sheffield was subdivided amongst the remaining children while Elizabeth moved into a house in the township of Howard.

On the 25 February 1929 there was a large gathering of family and friends at Violet Farm on the Burrum River to celebrate Elizabeth’s 94th birthday. Violet Farm, a subdivision of the old Sheffield Orangery made after Henry’s death, retained the original Sheffield homestead. The old house with all its memories, was lovingly decorated with streamers and greenery by the granddaughters and there were all the usual trappings of birthday cake and refreshments, musical performances and recitations. Speeches of course were made and the wish expressed that they would be celebrating this way again in another six years when Elizabeth Smith reached her hundredth birthday.[20]

Unfortunately, that wish was not to be granted and Granny Smith died in the old Sheffield homestead in November 1930, three months short of her 96th birthday. She left behind three surviving sons, 42 grandchildren, 71 great grandchildren and two great-great grandchildren.[21] She also left a wealth of stories of early pioneering life on the Burrum River – tales of courage, of hearts that dared, of loyalty, fortitude and perseverance that have been of lasting inspiration to her many descendants.

[1] Hudson, Frank “Pioneers” from “The Song of the Manly Men and other Verses” 1906 page 37, Poem printed in the Victorian Education Department 5th Grade Reader c.1930.

[2] “The Courier.” The Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864) 3 February 1862: p2.

[3] COTTON AND EMIGRATION TO QUEENSLAND. (1861, October 2). The Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864), p4. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

[4] Martin, Gwenda. BURRUM and BEYOND. Henry Smith “The First Resident” Page 2.

[5] Queensland History Blog Thursday September 15, 2011 https://queenslandhistory.blogspot.com/2011/09/queensland-financial-crisis-of-1866.html

[6] “GENERAL NEWS.” Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947) 14 November 1930: p6.

[7] Anderson, Elizabeth. “Memories of Elizabeth” a memoir.

[8] “Departures for England” Sydney Morning Herald (NSW: 1842-1954) Saturday 29 February 1868 p.8

[9] “VOYAGE OF THE RAMSEY—LONDON TO BRISBANE.” The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933) 26 January 1869: p5.

[10] “LAND SELECTIONS.” Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947) 18 September 1869: p2.

[11] Martin, Gwenda. BURRUM and BEYOND. Henry Smith “The First Resident”. Page 3.

[12] Martin, Gwenda. BURRUM and BEYOND. Henry Smith “The First Resident”. Page 3.

[13] “EARLY PIONEERS OF THE BURRUM.” Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947) 20 March 1916: p6.

[14] “Fifty Years Ago.” The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933) 14 July 1923: p18.

[15] ibid.

[16] “THE BURRUM.” Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947) 22 March 1870: p2.

[17] “BACKGROUND TO BURRUM:” Maryborough Chronicle (Qld. : 1947 – 1954) 14 February 1953: p2. Web. 27 Jan 2020.

[18] Martin, Gwenda. BURRUM and BEYOND. Henry Smith “The First Resident”. Page 8.

[19] CITRUS PAGES. Mandarin Hybrids.http://citruspages.free.fr/mandarinhybrids.php

[20] “PERSONAL.” Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947) 1 March 1929: 3. Web. 6 Jan 2021.

[21] “GENERAL NEWS.” Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 – 1947) 14 November 1930: p6. Web. 13 Sep 2020.

This is a great read of our real pioneers, thank heavens that these folk persevered. What a wonderful woman ‘Granny Smith’ proved to be, enduring the loss of so many of her children and surviving to 95 years.

Whenever I eat a mandarin I’ll think of Granny Smith and her extraordinary life. So much courage and perseverance.

I thoroughly enjoyed her story.

I’m always amazed at and admire the resilience of our ancestors. Thank you for sharing the story of Granny Smith.

This was a wonderful story for me to read. Granny Smith is.my Great Great Grandmother .I have a wonderful book of the first settlers on the Burrum

Thank you for your lovely comment Kris. I find our pioneer ancestors such an inspiration. They were so resilient and creative often in the face of terrible odds.