We become what we see!

For those who know me you know I am a public health microbiologist, a scientist. I have done a number of presentations for Scientists in Schools and had the interesting experience of a young lad about 11 years old very upset with his teacher as he thought they were getting “a proper scientist! Girls can’t be scientists!”

It is hugely important that people can see that girls can be scientists, plumbers, doctors, teachers etc and also that this is also true for different ethnicities, people of different backgrounds etc.

I can hear you saying but what does this have to do with family history?

Quite a lot actually. Many of our ancestors emigrated due to chain migration, someone in the family, church or village emigrated and sent word back and then others believed it was possible to also emigrate and succeed.

Housing affordability has been a major topic over the last few years because it is feared that the upcoming generation will not be able to attain the great Australian Dream of home ownership.

It is important to realise that for many Queenslanders in the early 1900s home ownership was not attainable.

It was the introduction, by William Kidston of the “Act to Enable the Government to Assist Persons in Receipt of Small Incomes to Provide Homes for Themselves”, (generally known as the Workers’ Dwelling Act of 1909) that this became even achievable. The idea was to assist workers, encourage thrift and provide health benefits as people would be in their own homes and also to assist the economy as homes were to be built rather than buying existing homes.

The government provided low interest loans (5%) over 20 years to low income earners who already owned land. The Government also regulated the type of home that could be built.

Requirements: Had to earn less than £200 gross income per annum, to own a piece freehold land free of encumbrances, or hold a miner’s homestead lease, or residence as granted under ‘The Mining Act 1898’ or a Town Lease. Had to be a British subject over 21 years. Could not own another dwelling in Queensland or elsewhere. Only then could the person then apply for a loan to build the house. The loan had to be used to build a home. It could not be used to buy a pre-existing home. The home had to be chosen from a set of standard plans. (You can download a booklet of approved designs from 1930 from Internet Archive at https://archive.org/ which has been digitised and placed online by the State Library of Queensland. Do a search for State Library of Queensland AND house).

If successful the client had to maintain land and house in tenantable condition for the life of the loan. This meant the house needed to be painted every five years with two coats of the approved paint and within the approved colour range.

The client had to pay all rates, taxes and other expenses relating to the land & dwelling and had to insure the property.

The client had to pay the monthly instalments and, in the event, they defaulted on a payment there was a penalty for failing to pay on time and arrears were charged at 10% interest.

It was considered in 1909 that the living wage for an unskilled labourer with three children was estimated to be £114 per annum in 1911. An engine driver, a skilled occupation but not a trade was listed as earning £187 per annum, both amounts well below the £200 maximum income for the scheme.

Over 30 years it is known that 19 058 workers’ dwellings were erected, 612 discharged soldiers’ dwelling (under a variant of the scheme that was then taken over by the Commonwealth returned Soldiers scheme) and 2 294 workers’ homes giving a total of 21 964 known loans for dwellings.

There were amendments to the scheme during the time period raising the maximum amount that could be loaned, raising the maximum income that could be earned, allowing the wife’s income to be used in calculating whether the applicant could repay the loan changing the interest rate and in 1934 changing the loan term to 30 years which decreased the monthly repayment amounts.

Finding out that your ancestor had one of these loans can sometimes be done by looking through Trove. The Board placed ‘Notices of Tenders’ for the building of the homes in the newspapers and often notices that the tenders had been accepted and who was the successful builder for the home.

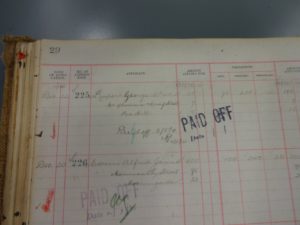

Housing loan 225

The Queensland State Archives have register books of indexes to the loan files. Unfortunately, it appears the actual files were not considered archival material and were not retained but you can obtain a fair amount of information relating to the loan from the loan books. There is an index book to the loans and then this tells you the loan number which tells you in which book your entry is listed. A search for “Workers Dwelling Board” as the Agency will take you to the numbers for the index (item ID 663720) and loan registers.

It is hard to determine exactly how many people got homes, but over 30 years there were 19058 workers’ dwellings, 612 discharged soldiers’ dwellings and 2294 workers homes erected totalling 21964 dwellings.

The scheme did not provide everybody with a home and there were strict eligibility requirements and when you remember that some of this time frame was during the Depression it is pretty amazing that around 17% of Queenslanders were helped to become home owners.

So, what does this have to do with today’s theme?

Don’t just look for your ancestor as what I have found is, that if one member of an extended family had a chance under the scheme, you will also find other family members, sometimes siblings but more often cousins. These may be cousins by birth or by marriage. In one family I researched, there were eleven members of the extended family that obtained loans under this scheme and paid off their home.

The house at Red Hill on the corner of Cochrane and Craig Streets

One of my family who took out a loan was Rupert George Weeks. His was loan number 225, taken out on 22 December 1910 for £187. It was for a home to be built on the corner of Cochrane and Craig Streets Red Hill, (interestingly in 1913 this was considered country as far as the Queensland Registry of Births was concerned but by the 1917 birth it was considered Brisbane). Rupert and Violet had married on the 7 April 1909. The loan was paid off on the 3 May 1921. Sadly, Rupert only had a couple of months to enjoy being a homeowner as he died of tuberculosis on the 29 July 1921, however his widow and two small children aged seven and four had a roof over their heads.

Sometimes it is a just a case of seeing that something can be possible.

What a fascinating set of records, thanks for posting Helen.