Every Ocean has a Distant Shore: Surgeon-Superintendents on Queensland Immigrant Ships

In 1986 Tavistock Publications in London and New York published the valuable PhD research of Dr Helen Woolcock, a Queensland occupational therapist, under the title of Rights of Passage: Emigration to Australia in the Nineteenth Century. The broad imprecise title probably was selected to attract a wide international audience because while the volume does cover emigration and the nineteenth century, it specifically concentrates on how the colony of Queensland set about obtaining a healthy population. The book is a thorough study of practices on board Queensland immigrant ships between 1859 and 1900. The role of the surgeons as officers in charge of hundreds of travellers within limited space far exceeded their medical duties as they also were responsible for the availability of food and fresh water, exercise and access to fresh air, entertainment, religious services and general discipline. Also considered are subjects like the constant juggling between legislative and administrative policies, passenger arrangements, the selection and experience of doctors and matrons, the problems created by captains and crews (confined exclusively to running the vessel, determining the route and wrestling with weather conditions) and patterns of life and death at sea.

Australian colonial authorities being well aware of the necessity of surgeon-superintendents on convict transports ensured the 1861 Act encompassing Queensland government regulations required a doctor on board every ship with more than twenty passengers and stressed his role as ‘guide, adviser and protector’ in addition to administering medical skills. Since the early 1830s, the New South Wales commissioners who initially set the standards applied to conveying immigrants, encouraged the surgeons by incrementally increasing salaries, rewarding them for satisfactory voyages. Several hundred surgeon-superintendents were appointed during the busy final forty years of nineteenth century Queensland.

Soon after Queensland separated from New South Wales, the colony established its own migration system, installing in London an Agent for Immigration, Henry Jordan, who offered incentives to mainly United Kingdom settlers to permanently relocate to newly designated districts. Jordan, by 1867 had introduced 36063 souls on eighty-five ships to Queensland. His successors, who included Archibald Archer and later his brother Thomas, Richard Daintree and a few ex-premiers, continued to lecture and attract immigrants to live on the seemingly endless acreages offered by the recent addition to Empire.

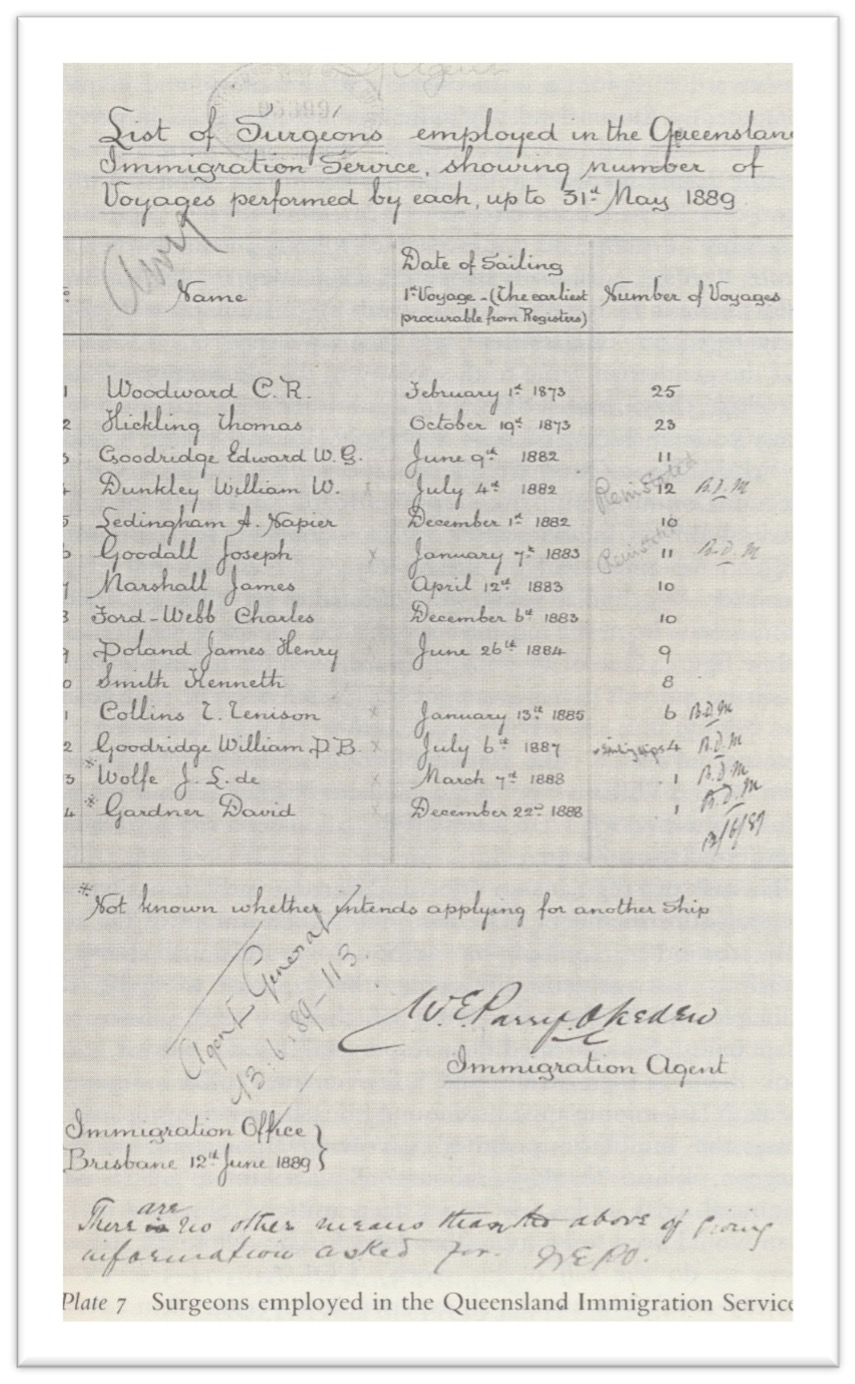

One of Woolcock’s illustrations, reproduces a list generated by W E Parry-Okeden, Immigration Agent between 1887 and 1889, detailing medical men who had undertaken multiple immigrant sailings between 1873 and 31 May 1889. At the top of this sixteen-man table are stalwarts Charles Woodward and Thomas Hickling who each had achieved twenty-five voyages within the nominated period. Both continued their role into the early 1890s with Woodward completing twenty-seven superintendencies before he retired in 1892.

List of Surgeons by W E Parry-Okeden employed in the Queensland Immigration Service. From: Dr Helen Woolcock’s publication Rights of Passage: Emigration to Australia in the Nineteenth Century.

Even though many of the immigrants had never even seen the sea before making this life-changing move, after a short time on board they became restless and bored with the limitations imposed by lack of space and activities. Surgeon-superintendents quickly adopted entertainment programs to amuse, divert or pass time. Often under the instruction of a fellow passenger schools for both children and adults were established offering at least the basic skills of reading and writing. Concerts were organized in the evenings where talented (or enthusiastic) globe-trotters sang, recited, acted or danced. On Sundays either the surgeon or perhaps a migrating man of religion conducted regular non-denominational religious services. Travellers were encouraged to keep diaries noting distances covered daily, sightings of birds or sea creatures or impressions of traditional ceremonies such as crossing the Equator. Handwritten newspapers featured on several voyages, some of which were printed on arrival. Grateful settlers also commissioned illuminated manuscripts or newspaper advertisements thanking the surgeons. All these diversions produced documentation such as school-masters’ reports (QSA), concert programs, the religious texts distributed at the end of the voyage, diaries and on-board newspapers, a variety of which can still be accessed, particularly at the John Oxley Library, which also holds photographs of ships and Queensland ports.

Additionally, the surgeon was required to submit a comprehensive voyage report to the Queensland Government at the journey’s end. The Health Officer on duty in each port of arrival also lodged an assessment following his examination of the ship and passengers – these also are available at QSA. Usefully soon after anchoring, local newspaper reporters sought information for eager readers expecting family, friends or employees. All these sources provide fascinating information concerning the passage of immigrant vessels.

We owe a great debt to the surgeons who undertook incredible risks amidst their responsibilities as their salary and job both depended upon getting the masses safely to Queensland ports ready for employment. In August 1886, while working on the Duke of Westminster, Woodward contracted smallpox from passengers who boarded after being released from hospital resulting in the surgeon’s quarantine on Bird Island in Moreton Bay. Hickling, with several of his colleagues, had contended with the 1885 outbreak of cholera, an always threatening disease due to indifferent water supplies available on ships. Both Dr James Poland (No. 9 on the list), and his wife (who was returning home after a short residence in Rockhampton), lost their lives in the wreck of the Quetta in Torres Strait in 1892.

The distant shore at the end of the long trips in sailing vessels dependent upon the Great Circle route for winds were usually known by the bays of arrival and included Moreton Bay, Hervey Bay, Keppel Bay and Port Dennison with Flat Top Island used for Mackay. Once steamships were introduced in 1881 with the Merkara using the Suez Canal opened in 1869, destinations usually were Thursday Island, Cooktown, Townsville, Bowen, Rockhampton, Maryborough and Brisbane. No doubt after months at sea the surgeon-superintendents were as glad to reach port as their charges but it took intrepid souls to repeat this adventure another twenty-five times.

I have Helen’s book. Must reread it. Thanks Jennifer for the reminder about it.