An Irish Lass: Catherine Hawe/Howe (1802- 1862).

This woman’s story started my passion for writing about my family history. I don’t know what her character was like before she was sent out to Australia, but I think she was or became a strong resourceful woman who cared about her family and community. In a strange twist, DNA testing to enhance my family history information, found out that I was not biologically related to her. Nevertheless, I think her story is indicative of many pioneer women whose struggle and voice is often lost and is worth telling.

Kilkenny Court, April 1828.

Whether she was a practiced criminal, or a poor Catholic girl driven to steal, her fate was sealed with the judge’s words:

‘Catherine Hawe, having considered your case and your defence, I find you guilty of stealing.[1]&[2] You are sentenced to seven years’ transportation to such parts beyond the seas as Her Majesty with the advice of the Privy Council should direct.’

With little chance of returning, seven years was really a life sentence. Perhaps she was relieved she was not to hang as was often the case, but women were a commodity in short supply in the colony.

Did she have a family of her own? Twenty-six years of age seems old to remain unmarried or childless. There doesn’t appear to have been a child with her on the ship. However, while wives of convicts were allowed free passage, even if she did have a husband or child, husbands were not given the same advantage.

Wherever she spent the next couple of months, either Kilkenny or Dublin prison, or if unlucky, at one of the many prison brigs, she would have encountered a crowded and dirty space, meagre and barely edible rations with violence and rapes by other prisoners and guards commonplace. It’s likely she was pleased when the City of Edinburgh departed in June 1828, carrying only women and children, prisoners were not chained.[3] There was no loss of lives, major outbreaks of illness or other disasters, but during the four month journey, Catharine would have experienced sights she had never seen before.[4]

Arriving at Port Jackson she would have noticed the brightness, the heat and the humidity unlike what she was used to. The land was not the rich green of Ireland but sage and olive with woolly trees right back to mountains. The town of Sydney, already starting to look like it remains in parts today had streets abounded with houses, stores, and other buildings. It had a botanical garden, churches and even a bank. Lastly, there were an awful lot of men. Transportation was still a very masculine phenomenon.

Trove. Female penitentiary or factory, Parramatta, watercolour, 15.9 x 25.7cm. Dated cc1826. Source: National Library of Australia. Call No: PIC Solander Box A33 #T85 NK12/47 Author: Augustus Earle (1793-1838)

It’s possible she was sent to the Parramatta Female Factory, the destination of all unassigned convict women between 1820s and 1830s.[5] Located on four acres on the traditional land of the Burramattagal clan of the Darug people, it was surrounded by a high stone wall and moat along the banks of the Parramatta River.[6] It served as an assignment depot, workhouse, marriage bureau and hospital. The women were expected to work and follow strict rules of conduct.

On arrival, they had to strip and wash from a trough out in the yard, their clothes were taken and they were given new ones. Called ‘slops’, each woman got two shifts in blue or brown serge, an under petticoat, a jacket and an apron, two calico caps, a pair of grey stockings and a pair of shoes. For Sundays, they had a white cap, a long dress with muslin frill, a red calico jacket, two cotton check handkerchiefs and a blue petticoat, a white calico apron and a straw bonnet, with a clothes bag to hold it all. They got no towels or combs.[7] As Catherine was sentenced for stealing clothes, she may have seen some irony in this handout.

Sometime before July the following year, Catherine was assigned to John Smith of Lower Portland where she most likely met the 48-year-old James Harrison who, having completed his sentence was now a free labourer.[8] He had been a tobacconist , receiving his seven years in 1823 for ‘stealing copper’.[9]&[10] One of the muster records notes his tattoos; on his right arm was a crucifix, ‘1801’ and the words ‘man and woman’. Apparently, a cross tattoo signified the faith of Christian sailors so they could be given a Christian burial if they died in a foreign place. The ‘1801’ may have been a political statement of support for the Acts of Union 1800 (enacted from January 1801) that followed the 1798 uprisings in Ireland and decreed Ireland and Great Britain to be a single kingdom. On his left arm were ‘hope’, ‘soldier’, a woman, a mermaid and an anchor.[11] Odd things for a tobacconist.

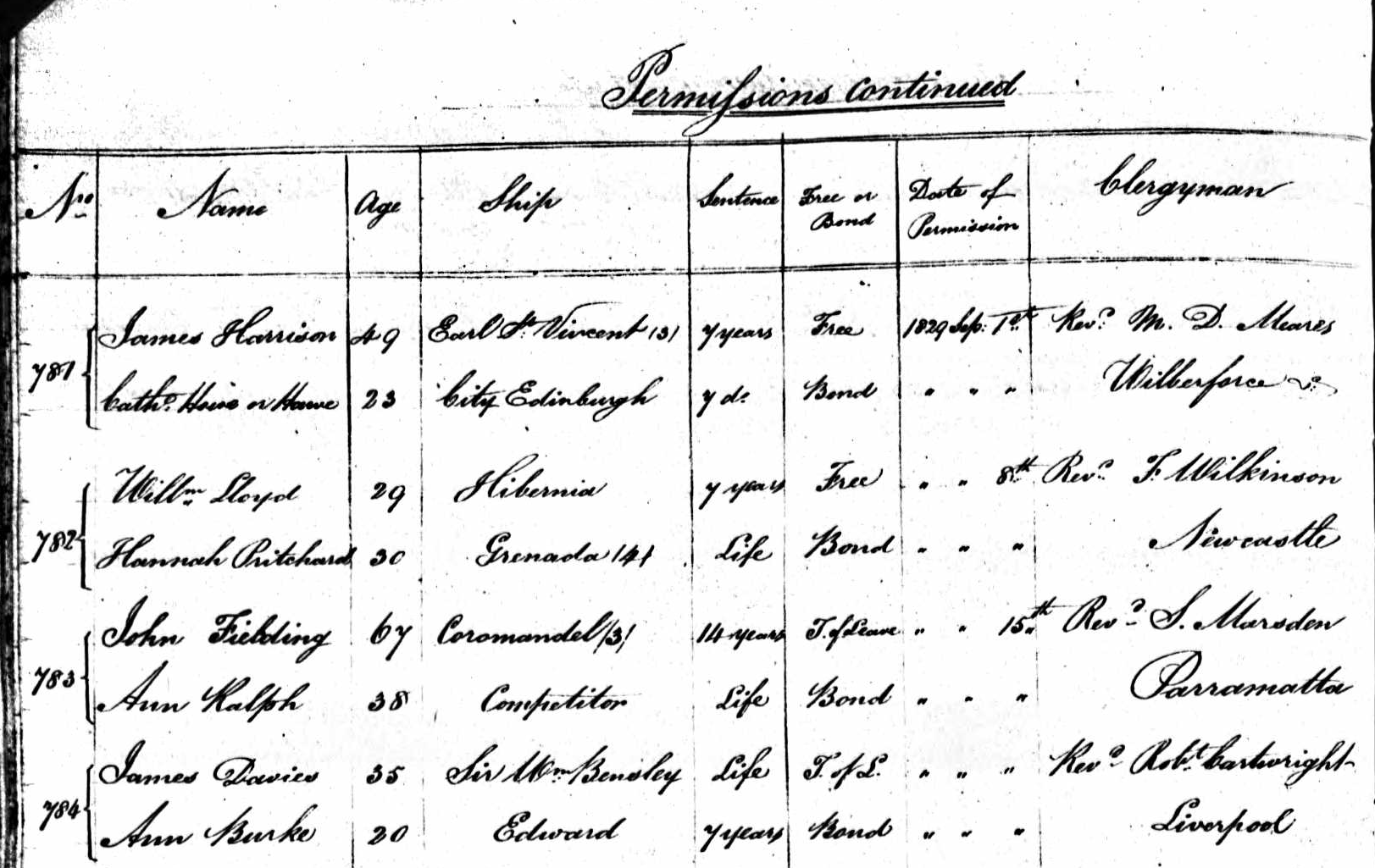

‘Permission to marry’ document granted to convicts James Harrison and Catherine Howe aka Hawe on 1 Sept 1829 whole page. Source: New South Wales, Australia, Register of Convicts Application to Marry 1826-1835 for James Harrison granted 1829, entry 777 on page.

As required, John Smith gave his permission when Catherine and James married at the Church of England Chapel at Sackville Reach, about 11 km from Lower Portland in September 1829.[12]&[13] Perhaps it was a pragmatic decision for them both as Catherine was a Catholic and James a Protestant and he was seventeen years older. Life along the river for this couple, whose decision to be here at all was not their own, was incredibly hard and James and Catherine would have had very little. Between 1829 and 1839 they had four children. If she was lucky, Catherine may have had assistance from one of the other women from the area, more likely she had to struggle alone.

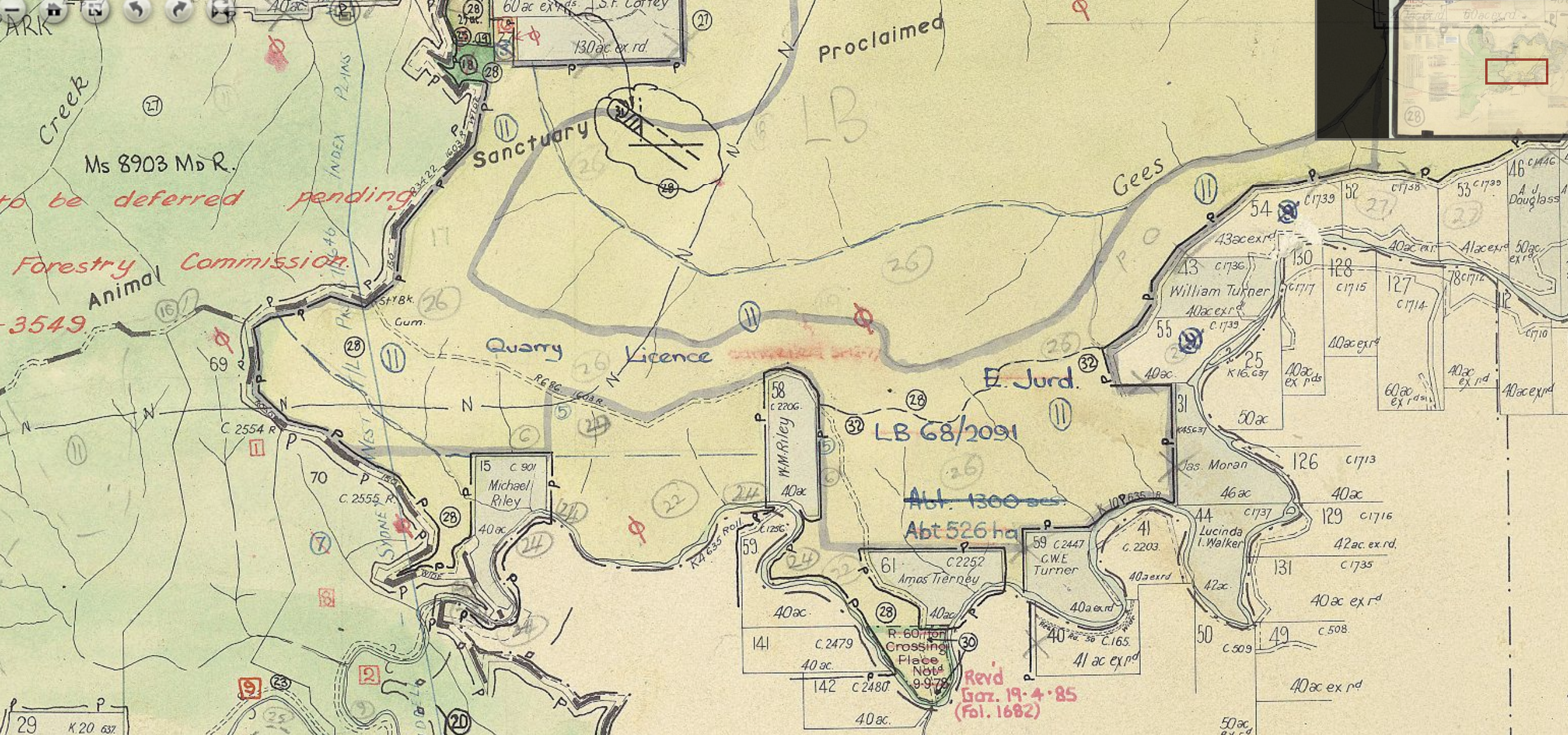

Around 1840, James Harrison disappeared. Did he abandon the family? Did his body finally succumb? Or was it foul play? It’s still unclear, but without a man to provide for her and her children, by 1841, Catherine had moved in with James Moran, another convict, who was now free.[14] James Moran with two others, was convicted of coining and counterfeiting six shilling tokens of the Bank of Ireland.[15] An ambitious crime, but still receiving seven years, he had arrived at Port Jackson in December 1823.[16] They seem better matched as James Moran was about the same age and a Catholic.[17] Seven years after James Harrison disappeared, James Moran and Catherine married at the St Rose of Lima Catholic Church at Half Moon Farm, Sackville Reach.[18] They now had six children together, with another on the way, making ten for Catherine. Just after their marriage, James Moran purchased 47 acres between the Colo River in the north, and the Coxs River in the south and west.[19]

James Moran land on the Colo River. Lot 31 of 46 acres. County: Cook. Parish: Colo. Image Name: County of Cook Parish of Colo. Dist Office Name: Metropolitan. Sixth edition. 1968. Source: https://hlrv.nswlrs.com.au/

According to birth registration records, Catherine was present at the births of many of her grandchildren and sponsor to most of them, as well as being a support to others in the community. When she died in 1862, James Moran and their daughter Agnes gave depositions at an inquest before a coroner and a jury. They said she had crossed the Colo River on foot several times to visit a neighbour whose wife had died. She apparently complained before going out that she had pains all over her. According to Agnes she was no better when she returned. Then: ‘in a short time commenced raving and talking. She was out and in her bed about a dozen times within half an hour she continued in this state the whole of Thursday and died about a quarter to twelve o’clock that night.’[20]

The verdict was that ‘death was bought on by imprudently passing through the river so often during the heat of the day, which caused inflammation of the lungs’. She is buried at the St Rose of Lima Cemetery, Half Moon Farm, Sackville Reach, Hawkesbury under the name Catherine Moran.[21] Up to her untimely death, fifteen grandchildren were born to her children whose father was James Harrison. Sadly, she did not live to see any grandchildren born to her children with James Moran, but there were many.

Not a bad legacy for a young woman convicted of stealing and ‘sent out’ to Australia.

[1] Catherine’s name is written as Howe, Haw or Hawe. Spelling was not a strong point for most folk, especially when the writers were usually English and the names were Irish. Being unable to read or write, her name was most likely spelt differently by whoever wrote it at the time.

[2] Ancestry.com (2009) New South Wales Australia Certificate of Freedom, 1810-1814, 1827-1967, database-on-Line, Provo, UT, USA. Original data – New South Wales, Butts of Certificates of Freedom, NRS 1165,1166,1167,12208,12210, reels 601,602,604, 982-1027, State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, NSW.

[3] 80 female prisoners, 12 free women and 36 children- https://www.jenwilletts.com/convict_ship_city_of_edinburgh_1828.htm

[4] https://www.jenwilletts.com/convict_ship_city_of_edinburgh_1828.htm

[5] Returns of ACCOUNTS AND PAPERS THIRTEEN VOLUMES, 1830, Oxford University, digitized 27 Jan 2009, notes that 80 females were received at The Female Factory at Paramatta from The City of Edinburg

[6] “The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Parramatta”

[7] https://atparramatta.com/discover/history-and-heritage/historical-places/parramatta-female-factory

[8] 1828 New South Wales, Australian Census (TNA Copy) online publication, Ancestry.com Operations Inc. 2007.

[9] Certificate of Freedom, 1828

[10] New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents, 1788-1942 for James Harrison, State Archives NSW; Series NRS 12188; Item (X31E) Microfiche: 659.Ancestry. Com database.

[11] State Archives NSW; Series: NRS 12188; Item: [4/4009A]; Microfiche: 653 (Man & Woman were also on his right arm and on his left arm were hope, soldier, woman, mermaid and anchor). also NSW Convict Indents, 1788-1842, online publication Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com – Indents First Fleet, Second Fleet and Ships, NRS 1150, microfiche 620-624. NSW State Records.

[12] New South Wales, Australia, Register of Convicts Application to Marry 1826-1835 for James Harrison granted 1829, entry 777 on page.

[13] Extract of Register of Births Deaths Marriages, Vol number 876, issued 1986.

[14] 1841 census has James Moran household which seems to include Catherine and her 4 children and another child, presumably James Moran (junior)

[15] Transcript of newspaper report of the 31 March 1823 trial. The connaught Journal

[16] Ref jenwilletts website

[17] Certificate of Freedom, 1830

[18] Transcript from handwritten entry Colo New South Wales, St. Rose’s R.C. Church marriage register. Also #1003A in Vol 95, NSW Archival Reel AO 5037.

[19] 46 acres purchased for 69 pounds, NSW Government Gazette 14 March 1848, pp387

[20] Page5, Sydney Morning Herald,1842-1854, Wednesday, 19 November 1862,

[21] Hawkesbury on the NET – Cemetery Register Half Moon Farm, Lower Portland, submitted by Coralie Hird from Death Certificate

Congratulations Yvonne. Well researched and written, bringing the life of a young Irish convict woman to life and adding to the stories of women in the early colony. I had to re-read the beginning to realize that your DNA had proved you were not biologically related to her, as you write “In a strange twist” you did the test “to enhance my family history information”.

Hi Catherine,

Thanks for the feedback. I probably didnt have to say anything about the DNA test. Maybe I should have added a bit more information. Its hard when you know the story so well and are editing it down. The twist was that I had done a lot of research on Catherine and her extended family and had grown quite fond of her. I did the DNA test because I wanted to find out some information about another part of my family, and in so doing it was confirmed that Catherine and I were not biologically related. But I am still fond of her.

Yvonne