Old photos from a Northern Territory cattle station.

On 22 July 2020, I was watching an edition of the ABC program The Drum, hosted by Ellen Fanning. One of the topics that night was the importance of understanding our own personal histories in relation to Aboriginal history in Australia and the need to be aware and take the time and effort to understand what role we played and/or our ancestors played. Truth-telling is fundamental to broader community understanding.

In this context Ellen Fanning spoke about her own family and how both her parents had grown up on sheep stations in Queensland. Recently she had found a photo album from about 1900 which had belonged to an elderly relative who had died. Among the photos was one of two Indigenous women dressed in starched, white uniforms sitting in the sun with a dog. They appear to have been domestic servants working on the sheep station and were taking a break from their daily duties. At this time Aborigines in Queensland were often sent away from their families at a very young age to work on pastoral properties such as this one. The women worked as domestic servants and the men as stockmen providing the cheap labour force for these properties and often those in control on these properties treated them very poorly.

Ellen Fanning asked the panel what she could do with her photo and the advice was for her to research the history of it. One of the panelists on the program that night was Jackie Huggins, an Indigenous Australian author, historian and Aboriginal rights activist.[1] She advised her to try and find out when was the photo taken and where? What were the women’s names? What were their histories? For assistance in doing this, Ellen Fanning was directed to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies which provides help with researching all aspects of Aboriginal family history.

In watching this program, I immediately thought of some photos, amongst a large collection of photos, that had been given to me recently by my cousin when she moved into a nursing home. They were taken by my cousin during a trip to Brunette Downs, a large sheep station in the Northern Territory, which she had visited in the 1950s to go to the Brunette Downs races held annually in June.

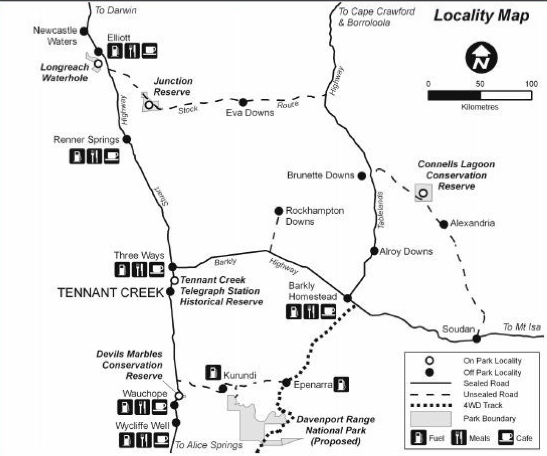

Map of Brunette Downs location in the Northern Territory. North of Barkly Homestead via the Tablelands Hwy.

Among the photos of people gathering to enjoy the social occasion of the races were ten photos of Aboriginal people who presumably worked on the station. These include one of my cousin holding an Aboriginal child believed to be the boss jackaroo’s child; three of Aboriginal women applying body paint and then holding a corroboree; an Aboriginal child being taken by aerial ambulance to Alice Springs; and groups of Aboriginal women and children on the property. As I looked at these photos I wondered who these women and children were and where they had come from? Are their descendants looking for them in an attempt to fill in questions of what happened to them? Descriptions (often using words which would be considered offensive today) were on the back of some of these photos as well as a couple of names which may be some assistance in identifying who these people were.

Life on Northern Territory cattle stations during this period was extremely hard for Aboriginal people. Frank Stevens’s book Aborigines in the Northern Territory Cattle Industry, published a number of years later in 1974, provides a stark description.

Perhaps nowhere in Australia have working and living conditions for Aborigines been so bad as on Northern Territory cattle stations. Though the Aborigines’ skill in handling cattle is acknowledged by their white employers, rarely have they gained recognition in any material way. None were paid full wages, many were fortunate if they received any cash wages at all, almost all lived in appalling conditions, and many were subjected to physical violence.[2]

I want to donate these photos to an institution which would provide an avenue for making them accessible. The Northern Territory State Library provides a place for Indigenous and other communities to donate material which is then preserved and made accessible through their Territory Stories. This site includes photographs, digitised manuscripts, maps; newspapers, etc.

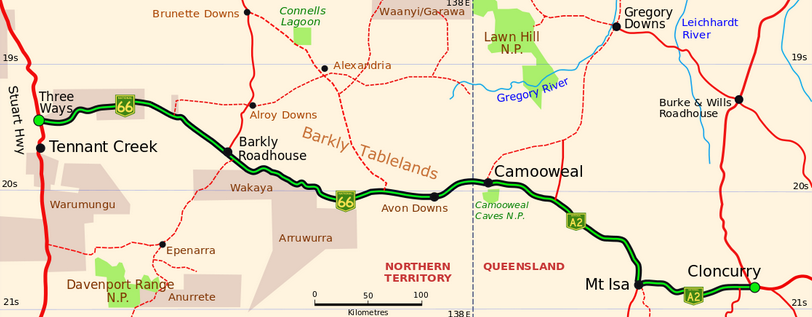

Barkly Highway (A2) in Queensland and the Northern Territory (Route 66).

If anyone has material that originated in Queensland, the State Library of Queensland also has photographs, manuscripts, oral histories and digital stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people across the State in the collections of the John Oxley Library. There also may be local libraries or Aboriginal organisations in various locations in Queensland and throughout Australia which would be interested in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander material.

When donating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander material, it is important to ensure that the organisation has Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Collection commitment policies such as

https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/SLQ_CollectionsCommitment_Single%20Page_WEB.pdf

or Content Guideline

https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/0019-408511-content-guidelines-memory-collections_0.pdf that demonstrate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as a target group. This means that the institution will make your resource a priority and ensure that the correct search terms are used to make the material culturally accessible by Indigenous people. This allows equitable access to the material.[3]

It is important for us as family historians to realise that all the resources and tools that we have at our disposal are not necessarily available to everyone. Tracing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family histories pose a unique set of challenges, for example, a baby whose birth was not registered will not have a birth certificate. If we come across any relevant photographs or documents during our family history journeys, we need to ensure they are offered to an institution or, if possible, relatives who may find them helpful.

I hope that in donating these photos, there may be someone who is trying to find relatives and if they know that their relative/s worked on Brunette Downs in the 1950s, these photos may help fill a vacuum. I would have liked to have given these photos directly to the descendants of the people in these images but, not knowing who they are, this is not possible

[1] Jackie Huggins is Co-Chair of the Eminent Panel advising the Queensland Government on the process truth-telling and future treaties with Indigenous peoples.

[2] F Stevens Aborigines in the Northern Territory Cattle Industry, Canberra, ANU Press, 1974 (pdf format).

[3] Information provided by Tania Schafer, Aboriginal Librarian from the State Library of Queensland.

I would urge everyone to deposit photos and written records relating to Aboriginal people, however small. Many of us are trying to find pieces to the puzzle. Photos are rare. Documents such as pastoral records can help to tell the story of where our ancestors were removed to. Often the family did not see them again. My Great Grandfather died at Headingly Station in search of rations. He rolled into a fire, according to the death certificate. I don’t even know where to start to find where he is buried. I know he worked at Alexandria because there are records stating this is what he said. Without those records I would not have known. It breaks my heart to think how awful those times were for him and others. You are doing the right thing Sue Bell.

Hi Julie

I noticed with interest you make mention of your father working on Alexandria Stn. How does one go about searching pastoral records for this information. My grandfather was a stockman and drover and was born in Roma Qld in 1891 but came to the NT in the early 30’s. We all knew he worked on Brunette but there were many stockmen there around the same time with the same given name.

My grandfather has been a hard man to research as he roamed all across Qld and NT under many alias’s.

Thanks for your comment. It is so important to donate photos of Aboriginal people when you come across them but it is often quite difficult to know which institution is the appropriate place. I hope you are able to find further records of your great grandfather in the appropriate state library or archives.

I agree with what you say “understanding our own personal histories in relation to Aboriginal history in Australia and the need to be aware and take the time and effort to understand what role we played and/or our ancestors played. Truth-telling is fundamental to broader community understanding. I know in generations gone by as many of these old people pass on many of the family photos don’t always get passed down, they simply get thrown out. My grandfather had 14 siblings and i have only managed to get one photo of his sibling – i got no photos of him.

Hi Barry, re researching your grandfather. Why don’t you start with the Northern Territory State Library https://lant.nt.gov.au/. Also try the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. https://aiatsis.gov.au/. These institutions may not be able to help but may be able to refer you on to other places. Good luck!