Travel on my mind

I sat down to start writing this blog post after the whirl of Christmas and Boxing Day was over. I’ve been thinking about the two trips I’m planning for this year: the AFFHO Congress in Sydney in March and the Unlock the Past Cruise to Alaska in September. My main activity over the past few weeks, however, has been to write up a family history for my dad’s ancestry, which has been somewhat on the backburner for several years. I wanted to get the basic details down in writing, and then take the time to craft a more readable story. The issue of travel came to mind when researching my paternal line.

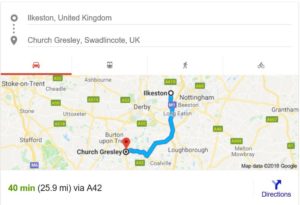

My grandfather was a Stirland and my grandmother was a Kinston. The Stirlands originated in the Ilkeston/Cotmanhay area which is on the Derbyshire side of the county border with Nottinghamshire. Primarily coalminers, they moved around the “Bermuda triangle” of the Notts, Derbys and Leicester coalfield in their search for work, which never seemed to be in short supply.

My grandfather was a Stirland and my grandmother was a Kinston. The Stirlands originated in the Ilkeston/Cotmanhay area which is on the Derbyshire side of the county border with Nottinghamshire. Primarily coalminers, they moved around the “Bermuda triangle” of the Notts, Derbys and Leicester coalfield in their search for work, which never seemed to be in short supply.

The Kinstons, on the other hand, were embedded in an area covering Stapenhill, Rosliston, Cauldwell (Caldwell) and Newhall, which are on the Derbyshire side of the county border with Burton-upon-Trent in Staffordshire. The Kinstons and related families either worked in the coalmines or in the pottery industry. The pottery was of an industrial nature, rather than the tableware more commonly found further north in Stoke-on-Trent. Burton-upon-Trent was, and still is, famous for its brewing industry.

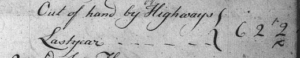

The county borders are very fluid in this part of the country and nowadays it seems to be one continuous mass of development. Only the signs at the side of the road tell you when you’ve crossed either a county boundary or are in a different place. In some villages the county border runs down the middle of the main street; this has meant that I’ve always focussed my research across at least two counties.

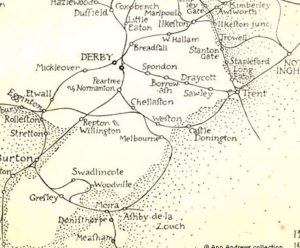

These two families became connected in the Swadlincote/Church Gresley area of South Derbyshire. The Stirlands came the longest distance from Ilkeston, but distance-wise, it’s only about 25 miles/37 km across this part of South Derbyshire. The Kinstons only moved within a radius of about 5-10km over a 100 year period! For both families, however, it must have seemed like moving to a different country.

I thought about how our ancestors would have moved around and realised that their options were limited. Most of my ancestors didn’t have the convenience of having their own car parked in their garage or driveway – they didn’t even have a garage or driveway to start with. The basic modes of transport would have been on foot, by horse, coach or carriage, by canal, by train.

Travel by water was a good option for those living on the coast as there was a significant level of coastal trade by sea around the UK. The extensive canal network throughout England and Wales by the end of the 18th century, especially, was a precursor to the railways in opening up long distance travel. Canals were built in the first instance to improve transport links between the industrial areas in the north of England, the source of their raw materials and the eventual market for finished goods. Maximum efficiency would dictate that canals went in a straight line between points A and B, with locks and other methods to deal with variations in landscape. I imagine that even if many of our ancestors arrived at their destination by travelling along a canal, they would have had many miles to cover cross-country to access the canal. My landlocked ancestors would have had a long way to go before actually reaching a port. Maybe this is why I’ve not found many from this side of the family who upped sticks and travelled to the New World. My maternal ancestors didn’t have such qualms, however, with many different lines all converging eventually on Liverpool. However, that’s another story.

For those without the means to pay for travel, ‘shanks’s pony’ was the only way to go. Shanks’s Pony, or its variant spellings, is defined as “one’s own legs and the action of walking as a means of conveyance.” (en.oxforddictionaries.com). The Romans built their roads in a straight line, which was an excellent strategy for moving large numbers of men long distances on foot, but you can shorten a journey considerably by cutting across country. How many of us take ‘short cuts’ to make our travel easier! It is estimated that the ‘average man’ could walk 20 miles a day. Add in the fact that the ‘average man’ may have been travelling with a wife and children and all their worldly possessions, however, and the journey starts to look like a major undertaking. Theoretically, travellers could try to hitch lifts with passing traffic but this might have been few and far between.

Travel on foot or by water could make even a short journey take a long time. For the more well-off ancestors, travel would have been easier if they had their own horse and coach/carriage but this was still a slow process. Roads in the early years were usually bumpy, rutted and full of pot-holes, dusty in summer and impassable in winter. This meant that travel was often restricted during the worst four or five months of the year.

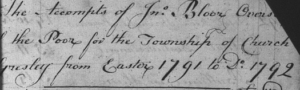

The first stagecoaches appeared in the 16th century, but their heyday came in the late 18th century as roads throughout the country improved. Parishes were responsible for the upkeep of roads within their area and men were generally required to spend time each year on road maintenance. The first turnpike or toll roads opened in 1663. I once did an analysis of the Overseer of the Poor Accounts for Church Gresley in Derbyshire. As can be seen from the following extracts from the accounts for 1791/1792, the Overseer, John Bloor, was out of pocket by Highways to the amount of £6.2s.2d. This sum would have been taken from the Poor Rate levied on all ratepayers in the parish.

As an aside, reading through the Churchwardens’ and Overseer of the Poor records gives an amazing insight to a parish. It’s worth checking out the FamilySearch catalogue to see if these have been microfilmed and digitised, otherwise they will usually be found in County Record Offices. As a reminder, you are now able to view many FHL films online at GSQ, but be aware that not everything in the catalogue is available online, nor available at GSQ.

As an aside, reading through the Churchwardens’ and Overseer of the Poor records gives an amazing insight to a parish. It’s worth checking out the FamilySearch catalogue to see if these have been microfilmed and digitised, otherwise they will usually be found in County Record Offices. As a reminder, you are now able to view many FHL films online at GSQ, but be aware that not everything in the catalogue is available online, nor available at GSQ.

Turnpike trusts were established in the 18th century. There’s an interesting article by Colin Waters in the October 2017 issue of Your Family History which looks at the job of a turnpike keeper. He explained that these trusts were set up by individual Acts of Parliament, which gave the trust the power to maintain certain stretches of road and to collect tolls from those wanting to use that road. The funds accrued were to be used for further improvements.

Public access to mail coaches from the 1780s reduced travel times significantly. It took 4½ days in 1754 to travel a distance of 210 miles/340 km from London to Manchester, but this had been reduced to just over a day in 1784. In the 1830s London to Birmingham, a distance of 127 miles/204km took about 11 hours.

A tram crossing the railway bridge in Swadlincote

South Derbyshire railways map 1903

The advent of the railways transformed the ability of our ancestors to move quickly, easily and relatively cheaply from one part of the country to another. By 1848 there were already 5000 miles of railway line in the UK. Railway networks were built and owned by many different companies. In 1923, most of the companies were grouped into the “big four”, the Great Western Railway (GWR), the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER), the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) and the Southern Railway (SR). These were subsequently nationalised as British Rail in 1948 and then privatised again in the 1990s.

Swadlincote Station

For a county such as Derbyshire the railways were a boon to the travelling public. The Midland Railway established its headquarters in Derby in 1839, which became a hub for the rail network and a main centre for engine and carriage maintenance. Two small books on my shelves are full of photos of trams and railways that carried passengers around this small part of the country. The Burton and Ashby Light Railways (Mark Bown, The Burton and Ashby Light Railways 1906-1927, Reflections of a Bygone Age, 1991), operated between 1906 and 1927; seven passenger trains a day in each direction called into Swadlincote on a loop branch line of the Midland Railways route from Ashby to Burton (Mark Bown, Swadlincote and district, Reflections of a Bygone Age, 1993.) The photos are taken from these two books.

Despite all these improvements in traffic infrastructure in the late 1800s/early 1900s, however, only a small proportion of the Stirland and Kinston families relocated long distance. The many members of one branch of the Kin(g)ston family who moved further north in Staffordshire and then migrated to Australia in the 1850s were in the minority.

Distance from Ilkeston, Derbyshire to Church Gresley, Derbyshire – 26 miles

So, if you have ever wondered how a couple from different places in different counties could have met, or why an ancestor was christened in a church in a different county, it’s always worth googling the distance between the various places. You may be surprised at how close they are. It is also worth looking at old maps to find out whether there were travel options other than Shanks’ Pony.

Until next time

Pauline

Comments

Travel on my mind — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>