Celebrations of Space: the Irish History and Society series

By Jennifer Harrison.

Tipperary History & Society Book[1]

Following the wonderfully successful Irish seminar GSQ conducted in October 2020, it occurred to me that members might benefit from knowledge of a series of books currently in production in Dublin which provide wonderful contextual material for those researching individual counties. Since 1985 Geography Publications have produced substantial volumes under the collective title of History and Society. Each book ranging between 500 and 1000 pages examines an individual county. By the end of 2020 with the issue of Kerry, twenty-eight of the thirty-two counties have been covered.

Geography Publications is guided by historical-geographer William Nolan, Emeritus Professor of Geography at NUI Dublin and his wife Teresa. Nolan established firm local and family history connections with an earlier book, Tracing the Past: Sources for Local Studies in the Republic of Ireland , (Geography Publications, 1982), a small volume of 150 pages, which introduced researchers to the ‘celebration of space’, a concept basic to an understanding of Ireland and the Irish. After establishing the administrative framework and its divisions, through the use of surviving sources and traces, Nolan took the story of place and population from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries with judicious use of maps, plans, illustrations and detailed descriptions. A copy is held in the GSQ library providing a wonderful start to understanding the physical landscape of Irish ancestors.

The History and Society series commenced with Tipperary in 1985 and its structure has served as an effective model for subsequent volumes.[1] Nineteen interdisciplinary studies by academic and local experts offered chronological and thematical essays drawn from the fields of archaeology, history, geography, Irish literature, folklore, religion and planning, a listing which has been adapted and expanded to capture characteristic vagaries pertinent to distinct areas. Each chapter is supported by maps, diagrams, tables, illustrations and photographs considerably enhancing the text. In short, every book commences with pre-history and concludes with twentieth-century issues, from political intrigues to sporting activities, with chapters numbering up to thirty-eight. While well-sought ancestors may prove elusive throughout the earlier sections on geological quirks and the effects of ice on topography through to medieval times, these topics do provide a firm foundation for a constantly evolving story, establishing a detailed grounding for later idiosyncratic developments influencing landscapes, all contributing to the island of Ireland.

The initial paper in Tipperary, ‘Some reflections upon the local dimension in history’ by Cambridge Fellow, Nicholas Mansergh, described the development and relevance of local studies, not only for the selected county but also as a discipline. A chapter of particular interest concerned ‘The Whiteboy movement, 1760-1780’ by Maurice J. Bric, which outlined the origins of agrarian outrage, one of the most significant crimes responsible for the transportation of numerous Irish rural inhabitants to Australia, especially in the years 1822-1825. (This theme was continued by Flannan Enright in his article on the Terry Alts in the Clare volume.) Kevin Whelan contributed a valuable article on ‘The Catholic Church in County Tipperary, 1700-1900’, pertinent to the background of Irish clergy particularly those trained at the Christian Brothers college at Thurles who later migrated to the distant colonies. On the other hand, Australasian priests who trained at Carlow College were investigated by John McEvoy for that county’s edition. Also for the benefit of many challenged by tangled property ownership and taxation, the work by T. Jones Hughes, ‘Landholding and settlement in County Tipperary in the nineteenth century’ explored the estate system, the role of towns, the importance of the farming community and the prevalence of the poor in chapel villages giving a solid framework on which to understand the emigration of such large numbers from this county.

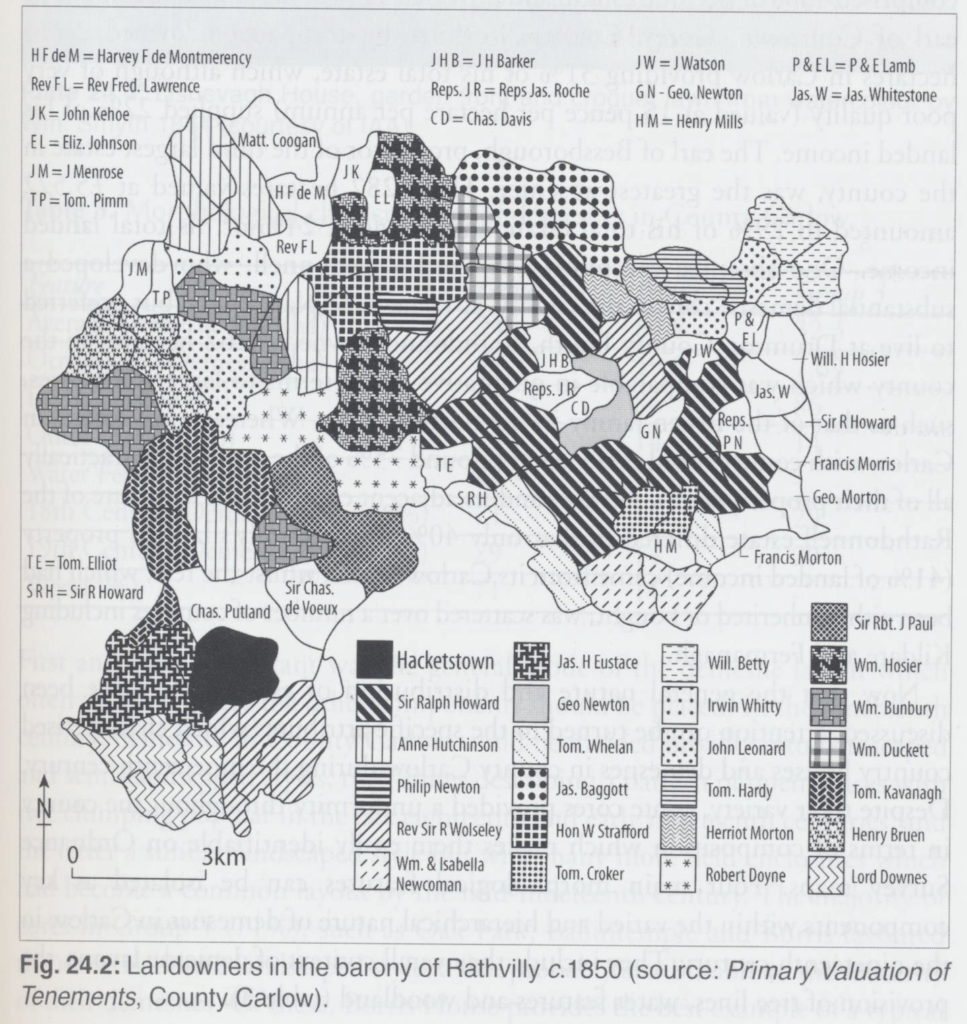

This map of Landowners in Rathvilly barony, Co. Carlow, around 1850 is typical of the informative maps, plans, tables and diagrams which illustrate the articles in History & Society volumes. For those seeking landlords, tenants or owners, such detail could represent pure gold.

The breadth of subject matter and explanations of complexities abound among the chapters which now total well over four hundred, a quite daunting and overwhelming achievement despite the opportunity here to explore just a few topics. In the following descriptions the title of the article usually will indicate the particular county volume in which it appears; for those not quite so obvious the county book concerned has been indicated in brackets.

Not unexpectedly, stories of the Great Famine, An Gorta Mór, have featured and serve to indicate its very disparate effects in different districts. For example, Gerard MacAtasney’s, ‘Consequences of the Great Hunger in County Leitrim’ contrasted with Christine Kinealy’s ‘The Response of the Poor Law to the Great Famine in County Galway’. Corresponding loss was explored in papers on emigration, both to Great Britain as well as remote overseas destinations of which Patrick Fitzgerald’s ‘Migration in Monaghan history’ and Bruce Elliott’s (Kilkenny) are a couple of good examples. Further, essays on place names and mapping prove incredibly informative for distant researchers. Breandán Ó Madagáin in Clare investigated ‘Eugene O’Curry 1794-1862 Pioneer of Irish Scholarship’, a stalwart of naming procedures adopted by Ordnance Survey, whereas Fiachra MacGabhann offered further explanations in ‘Place Names of County Mayo’. Valuable cartographic work by Arnold Horner and his assessment of ‘William Larkin and the mapping of County Leitrim in the early nineteenth century’ offered great insights.

Monaghan History and Society book

Michael Gibbons entrances with his contribution, ‘Croagh Patrick and prehistoric mountain pilgrimage in Ireland: Modern Myth or Ancient Reality’ indicating earthly rewards which came from doing penance in the ritual tapestry of Mayo. Family histories appear from time to time such as ‘The Browne families of county Wexford’.

Since the Tipperary* introduction to the series, subsequent volumes continued the exploration of economic, cultural and social changes at county level. In order of publication these were: Wexford (1987)*, Dublin (1992), Waterford (1992), Cork (1993)*, Wicklow (1994)*, Donegal (1995)*, Galway (1996), Down (1997), Offaly (1998)*, Derry & Londonderry (1999), Laois (1999)*, Tyrone (2000)*, Armagh (2001), Fermanagh (2004), Kildare (2006), Clare 2008), Carlow (2008)*, Limerick (2009), Longford (2010), Mayo (2014)*, Cavan (2014)*, Meath (2015), Monaghan (2017), Roscommon (2018), Leitrim (2019) and most recently Kerry (2020). According to the company’s website, www.geographypublications.com those marked with an * have proved so successful that currently they are out of print but occasionally can be located on book sites. While the benefits offered by these volumes cannot be exaggerated, they are expensive to purchase 12,000 miles from publication, as they average between €50 and €60 each with postage to Australia amounting to approximately a further €25 – probably sufficient reason why libraries should be urged to obtain them.

Locally in Brisbane, the State Library of Queensland holds eleven of the twenty-eight volumes: Cork, Derry & Londonderry, Donegal, Galway, Kilkenny, Laois, Offaly, Tipperary, Tyrone, Wexford and Wicklow. For travellers further afield the Society of Australian Genealogists in Sydney have: Cork, Down, Tipperary, Waterford, Wexford and Wicklow and the Australian National Library in Canberra holds several including Cork, Donegal, Galway, Kilkenny, Tyrone, Wexford and Wicklow while other counties may be available within Australia on inter-library loan.

Travelling through Ireland in 1842 William Makepeace Thackeray was aghast to realise, ‘… there are eight millions of stories to be told in this island. Seven million nine hundred and ninety-nine thousand nine hundred and ninety-eight more lives than I, and all brother Cockneys, know nothing about’. For Cockneys, read Australians, then recognize the value of your family history research and why it requires informed sources like this series.

[1] Cover illustrations have been carefully selected to reflect the essence of each county’s personalities. Tipperary features a 1973 photograph of Holycross Cistercian monastery which contrasts with native-born son Henry McManus’s 1830 depiction of ‘A Market in Monaghan’ (below) to introduce that county.

Comments

Celebrations of Space: the Irish History and Society series — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>