Edith Matilda and her sisters

Edith Matilda

I remember my great grandmother, Edith Caller (rhymes with “valour”), as a happy, snowy-white haired lady who seemed to chuckle a lot; I’d say she was jolly. To me, she was “Nanny Caller” who lived in an old timber house set on a large block in Putney, on the Parramatta River. There was an extensive vegetable garden, an array of fruit trees and still plenty of room for ballgames and chasings during family gatherings. We always felt very safe and loved visiting her. We never had the slightest inkling that she’d had what I have since discovered was a sad childhood.

Edith was born Edith Matilda Bulmer in Taree, New South Wales on 21 February 1891 to Robert Magasson Bulmer and Amelia Shoesmith [1]. Her older siblings were Sarah Jane, and Maud. Another sister, Amelia, had died in infancy. After Edith came Ellen Vera and Andrew Harold. The Bulmers and the Shoesmiths were large pioneering families in the Manning River District.

Robert passed away in March 1896 at the age of 33 when Edith was just 5 years old. Amelia was left with 5 young children ranging in age from 1 to 10. Robert’s cause of death was given as phthisis (tuberculosis), an illness he had for about seven years [2]. Just seven months later, in January 1897, 18 month old Andrew passed away, it is suspected from phthisis. Amelia decided to move to Sydney with her young daughters. Perhaps she felt a new start away from recent sadness would improve their lot, perhaps she wanted to find work to support her girls and felt there were more opportunities in the city, perhaps she wanted to protect her girls from threat of phthisis which was prevalent in the Manning though it was also occurring in the city. Perhaps it was all or none of these reasons but whatever her motivation, she moved away from Taree, away from her own mother and her extended family.

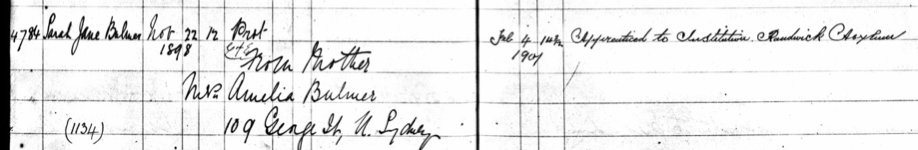

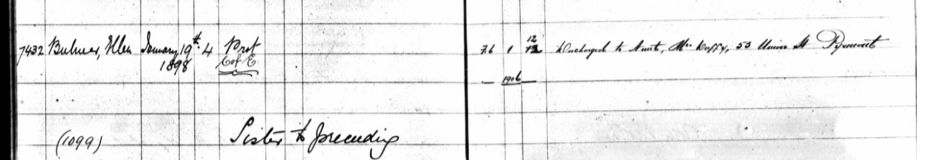

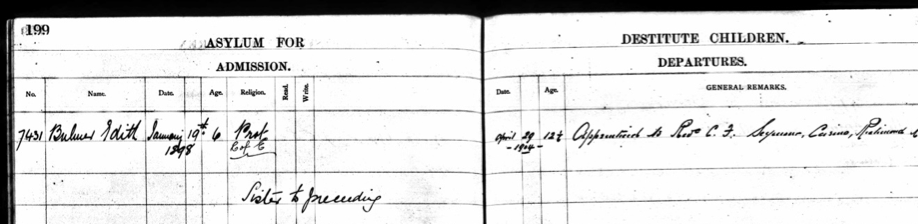

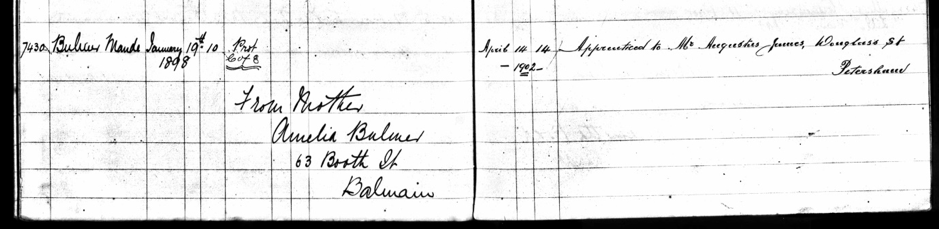

Life in Sydney with four young daughters to support was presumably tough for Amelia. In January 1898, Amelia placed Maud (10), Edith (6) and Ellen (4) into the Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children. Initially, Sarah remained with her mother, however in November, Amelia left Sarah at the Asylum also. [3]

Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children

When the Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children was first established in Randwick, Sydney in 1858, its aim was to care for abandoned children or those whose parents exhibited “dissolute character”. In addition, single parents could place their children in the Asylum upon payment of a fixed fee. It may be assumed that Amelia did this as from 1888 Government funding to the Asylum had ceased. Further financial support came from bequests and public donations.

The Asylum aimed to be self-sufficient. The Randwick site included a farm where the boys learnt farming skills while the girls were trained in domestic duties.

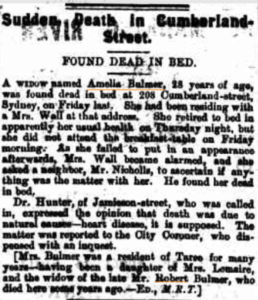

Parents could and did reclaim their children. It may well have been the Amelia’s intention to be reunited with the girls once she was “on her feet” but a few months later tragedy struck yet again. Amelia was found dead at her lodgings in Sydney in July 1899. She was just 28 years of age. [4]

While heart disease was suspected by the attending doctor, a post mortem examination later found “no external marks of violence and was of the opinion that death was due to chronic kidney disease viz natural causes…”[5]

While heart disease was suspected by the attending doctor, a post mortem examination later found “no external marks of violence and was of the opinion that death was due to chronic kidney disease viz natural causes…”[5]

So, what became of Edith and her sisters, now four young orphaned girls? Read on….

Following the inception of the State Children Relief Act, 1881 (Act 44 Vic. No. 24, 1881) a system of “boarding out” or apprenticing children from institutions was adopted. This applied to children of around the age of 12 years until the age of 19 when they were no longer the responsibility of the Asylum.

The boarding-out system, which had its origins in the British Isles in the mid-nineteenth century, became a reality in New South Wales in the 1880s. The idea was to board out orphaned and homeless children in homes of respectable persons under proper supervision, instead of herding them together in large public institutions. The foster homes for these children were frequently situated in country or rural districts where the children showed a marked improvement in health owing to pure air, greater variety of food and lessened risk of contagious diseases.[6]

By 1909, of the state’s nearly 4000 destitute children, some 57 per cent of had been placed with foster parents as boarders with maintenance, while 41 per cent were boarding with families as apprentices.[7]

One State Children’s Relief Board report described the destinations of 103 of its girls and 128 of its boys:

All the girls were apprenticed to domestic service, and the majority of the boys have been apprenticed to the dairy farmers, with whom they had been boarded. The following are the details:— Boys indentured to farmers, 103; gardeners, 5; hairdressers, 2; grocers, 3; saddler, 1; bakers, 3; tailor, 1; painters, 2; butcher, 1; undertaker, 1; carpenter, 1; provision merchant, 1; storekeeper, 1; chemists, 3; total, 128. [8]

The Admission and Departure documents from the Asylum revealed what happened next in the lives of the Bulmer girls. NSW BDM Indexes, Electoral Rolls and death notices tell us the rest.

Sarah Jane’s apprenticeship [9]

Eldest sister Sarah Jane was apprenticed to the Randwick Asylum itself in 1901 at the age of 14 and worked in either the laundry, the kitchen or as a cleaner. She’d likely to have been discharged from the Asylum’s care at 19. In 1907 Sarah Jane (21) married Charles Edward Spence Gifford. She and Charles had five children together. Sarah passed away at Five Dock in 1941 at the age of 55.

Ellen’s discharge [10]

Youngest sister, Ellen, was discharged from the asylum in 1906 at 12 into the care of her aunt Mrs Duffy, Amelia’s younger sister May, who lived in Pyrmont. Ellen married Walter Hellyer at age 17.[11] Ellen and Walter had 3 daughters. After Walter passed away in 1967, Ellen remained in the family home at Gladesville passing away at the age of 84.

Edith’s apprenticeship [12]

Unlike her sisters, Edith didn’t remain in Sydney after leaving the Asylum.

In 1904, Edith was apprenticed to Reverend Charles Frederick Seymour, of St Marks Anglican Church, Casino in northern New South Wales. Rev Seymour and his wife had at that time three young children. I imagine Edith would’ve been involved in carrying out domestic chores and caring for the children.

Edith did however return to Sydney in 1907, pregnant, and gave birth to a daughter, Doris May at the South Sydney Women’s Hospital, Newtown.[13] No father was listed. Edith was 15 but on baby Doris’ birth certificate Edith’s age was given as 18. The hospital had begun its life over a decade earlier with the rather “descriptive” name of “Home of Hope for Friendless and Fallen Women” and operated as a rescue home and lying in facility for unmarried pregnant women. Adoptions were frequently arranged but surprisingly, despite being so young, Edith was able to keep her daughter. It’s unknown how Edith supported herself and her baby, though she did have 2 sisters and an aunt in Sydney who I like to think may have offered assistance.

Edith married Alfred Edward Caller just two years later in 1909 at the Whitefield Congregational Church.[14] She gave her age as 22 but in reality she was only 17. Eighteen months later, Alfred purchased land in Pellisier Rd Putney and built the family home. Young Doris was joined in time by half siblings Phyllis, Charles, Ella (my grandmother), Beatrice and Hazel. Alfred died in 1936. Edith remained in her Putney home until she passed away at 77 in November 1968.[15].

Maud’s apprenticeship [16]

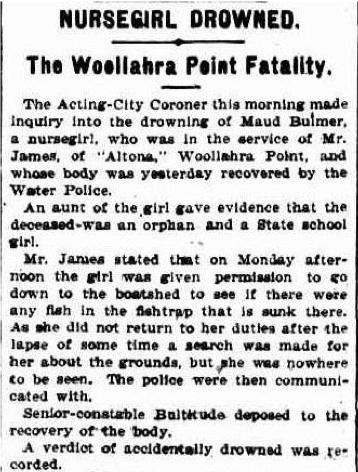

The saddest story of all, however, belongs to Maud. In 1902, at the age of 14, Maud was apprenticed to Mr Augustus James, a highly regarded barrister of Petersham. Augustus James and his wife Altona, had two small daughters, and Maud was nurse girl to the youngsters.

During his subsequent career, Augustus James became a Crown Prosecutor, King’s Counsel, held positions of State Representative for the Goulburn Electorate, Minister for Education, Minister for Labour and Industry and was a Supreme Court Judge up until his death in 1934. He was a man of ambition and influence.[17]

“Altona” as seen from Sydney Harbour today [18]

In 1903, construction of a luxury, 2 storey, Italianate mansion was completed for the James family at Woollahra Point overlooking Sydney Harbour. It was named “Altona” in honour of Mrs James. Two more children were born and Maud was kept extremely busy, tending to needs of the growing family.

Tragically, in March 1905, Maud’s young life was cut short. According to newspaper reports Maud has asked her mistress for permission to check the fishtraps in the Harbour. Permission was granted but she didn’t return. Water Police conducted searches, but Maud’s body was not recovered until two days later. Her death was deemed accidental drowning. [19]

Tragically, in March 1905, Maud’s young life was cut short. According to newspaper reports Maud has asked her mistress for permission to check the fishtraps in the Harbour. Permission was granted but she didn’t return. Water Police conducted searches, but Maud’s body was not recovered until two days later. Her death was deemed accidental drowning. [19]

I do wonder if there was more to the story. Maud was just 17.

[1] NSW Transcriptions, Marilyn Rowan. Birth Edith Matilda Bulmer 1891. NSW BDM Index.

[2] NSW Transcriptions, Marilyn Rowan. Death Robert Magasson Bulmer 1896. NSW BDM Index

[3] NSW Register for the Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children (1852 – 1915)

[4] The Manning River Times and Advocate for the Northern Coast District of NSW (Taree, NSW: 1898 – 1954) Wednesday 19 July 1899, page 2

[5] Sydney, Australia Morgue Register of Bodies 1881 – 1908 for Amelia Bulmer. North Sydney Morgue Register of Bodies Received 1881 – 1904

[6] Ramsland John, Children’s Institutions in Nineteenth Century Sydney, Dictionary of Sydney 2011.

[7] Ramsland, ‘Development of Boarding Out Systems’ p196

[8] State Children’s Relief Board, Report of the President, 5 April 1886, p29

[9] NSW Register for the Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children (1852 – 1915)

[10] Ibid

[11] Sydney Australia Anglican Parish Reg 18142011 for Nellie Vera Bulmer – marriage, 1910

[12] NSW Register for the Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children (1852 – 1915)

[13] NSW Birth Index Doris M Bulmer 1907 Reg: 6060/1907 District: Newtown

[14] NSW Transcriptions, Marilyn Rowan. Marriage Alfred Edward Caller and Edith Matilda Bulmer 1909. NSW BDM Index

[15] NSW Transcriptions, Marilyn Rowan. Death Edith Matilda Caller 1968. NSW BDM Index

[16] NSW Register for the Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children (1852 – 1915)

[17] NSW State Archives and Records: Honourable Augustus George Frederic James KC BA

[18] “Altona” – photo owned by author

[19] Australian Star (Sydney, NSW : 1887 – 1909), Tuesday 7 March 1905, page 5

This is a very sad story – wonderfully written.

Love your story,think you should write a book ,this was very interesting,

What a sad family story, those poor young girls at the mercy of the institutions. Very well researched and presented.