Finding my father.

by Christine Leonard.

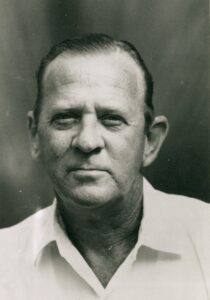

Portrait of Greg Wall. From author’s personal collection.

My father died when I was sixteen. At the time I was in my seventh year of boarding school in Australia as my parents lived in Papua New Guinea, where I was born. Dad’s death was a shock, completely unexpected; he was tall, lean, strong and fit. We, as in my brother and I, assumed Mum would go first; she was the one with a heart condition. There again, Dad smoked up to 80 cigarettes a day, enjoyed more whisky than he should have, and when I flew home for the holidays, my grandmother bought out the local newsagent’s supply of Quick Eze for me to take up for Dad’s indigestion.

Fast forward 48 years, equal to Dad’s age when he passed, I found myself researching his family and ultimately wanting to learn more about Dad. Gregory Wall was his name, no middle name, and the first was universally shortened to Greg. Dad’s family weren’t close, and growing up on remote plantations in the New Guinea islands ensured I had limited contact with them. Memories of Grandad Wall are vivid, as he played a large part in my younger life when I visited him in Eimeo, Queensland, during the May school holidays. He introduced me to Irish stew, a ‘thunderbox’ toilet shrouded in fernery under the house, the meat safe kept cool by moistened calico and so much more. My paternal grandmother, Chrissie Wall, passed three years before my birth, but I did know Dad’s siblings and my first cousins.

Despite the love between us, being sent to Australia at nine years of age inevitably fostered a gulf between me and my parents, a gulf that widened over my formative years. Dad was strict; a withering look was enough to replace a ten-minute verbal barrage. I was held to high expectations, especially on how to behave and to remember my manners. But we also had our special times together. When I was home from school, I loved riding around the plantation on the back of his motorbike, tearing along bush tracks, weaving around potholes and stony outcrops, and splashing through shallow creeks.

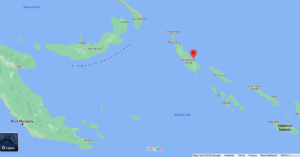

Kieta, Bougainville Island, PNG. Google map image 2022.

Losing Dad in my second last year of secondary school not only left me bereft, but it robbed my chances of finding a stronger foothold within his orbit. Losing a parent in childhood narrows the prism through which memories are formed. I would say that Dad was a very conservative man, I don’t think he wore a coloured shirt until I was in my teens. Working in remote places in the bush, on tractors, motorbikes, overseeing the planting and processing of cocoa and copra, his forever uniform was a khaki short sleeve shirt and shorts. He wore long trousers and a white shirt when he came home and showered for late afternoon drinks and the evening meal.

Dad was a man of few words and didn’t suffer fools. I grew up on plantations in colonial times where whites were the ruling class, no matter how respectful one might have been towards the indigenous workers and neighbours. As children, there are things we sort of know but can never articulate. For instance, I knew my dad had a different persona around adults to how he was with me. I think he was a great raconteur. I remember scenes of him telling some story, and the men in the room would erupt in gales of laughter. He swore like a trooper but not in my visible presence, except for the word ‘bloody’. I suspect in the ‘50s and ‘60s, most Queensland men who grew up in the country would have found it nigh on impossible to string a sentence without at least one expletive.

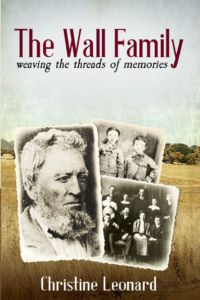

The Wall family book front cover.

I recently self-published a family history on the Walls, starting with my great-great grandfather who was transported to Van Diemen’s Land in 1835. The book covers William Wall, the convict, the two wives he outlived, their 13 surviving ‘Currency’, and the two generations that followed. I limited my dad’s life to two pages in the interests of balance, but it made me realise that my memories of the man, whose life ended in 1971 with his sudden death on Bougainville, are those of a child. Greg Wall’s grave was the first one dug in the new cemetery for Kieta, the small township some 14 miles away. It was a huge funeral, and I think now about all those people whose stories, decades later, are beyond reach. My children knew their maternal grandmother, my mother, who passed away in 2013, but Dad figures in but a few rarely seen snapshots.

When we embark on family research, whether one or five generations back, we tell ourselves it’s for our descendants so that they might know where they’ve come from, but equally, it is for us as researchers. Understanding who you are writing for is critical, as it will inform you how best to present your family’s history. The unexpected joy for me has been in those moments when I discover a gem, more often through oral history, that brings to life the person staring out of a faded photograph. Our tribes are more than the dates of births, deaths, and marriages. Finding stories that reveal their character and flaws is where the gold lies.

I’ve been on a search to capture stories of Greg Wall, the man. He was born in Winton in 1922, and the only contemporaries I can draw on are family friends who were considerably younger than Dad. My aunt would have many amusing tales, such as when Greg was courting my mother, or when they came down on leave from Bougainville, but alas, she has Alzheimer’s. You could say I’m reaching into the bottom drawer for email addresses of people who, I’m embarrassed to say, I haven’t been in touch with since Mum’s funeral. A good researcher however leaves no stone unturned, and most if not all those you contact, no matter how long it has been since you were last in touch, will be delighted to chat about old times.

The feedback can be ‘hit and miss’, but the ‘hits’ are wonderful. If friends of my parents are within driving distance, I take a small notebook, something for lunch or refreshments, and my trusty phone to record their reminiscences. If the person being interviewed is relaxed, it is surprising how much they enjoy telling a story and memories improve with the telling. An important lesson for me is to prepare guiding questions before the visit just in case, and it goes without saying, always make sure they agree to be recorded. Transcribing audio recordings is time-consuming but worth the effort, and it is an excellent medium one can play back at any time in the years to come.

Author’s website: www.leonardstories.com

To purchase book: https://www.gsq.org.au/gsq-shop/the-wall-family-weaving-the-threats-of-memories/

What a lovely story. You’ve said many things that resonate with me. I enjoyed reading it very much and I’m envious of your writing style. Thank you.

Yvonne Tunny

Thanks Yvonne, your feedback is much appreciated

In July 1969 I was transferred to Lae PNG as the local Representative of my Company to assist the Australian Government through the PNG Dept of Trade and Industry in the transition of the Local Village People from a barter system to a Cash trading society.I travelled all over PNG. Regularly visiting Bougainville. Generally I would fly in from Rabaul to Buka and after a day onto Kieta. I can always remember Mal Mal Drive and the beautiful Rain Trees. Unfortunately the road was always “chewed-up” by the heavy machinery going up to Panguna Mine. After a few days I would fly onto Buin before returning home to Lae. My business was with the Agricultural Officers of the Dept of Ag Stock & Fisheries and also the Co-operative Officer of Dept of Business Development. Through those connection I may have met your Father. I did visit Innis Plantation and met the famous Coast Watcher. I regret that as it was a long time ago my memory is fading.I always enjoyed my visits to Bougainville. Your story brings back to me a wonderful time of my life – Thank you. Paul Cummings

thanks Paul, your job must have been very interesting. Cargo Cult was quite strong in some places around that time. Mum had a shop in Kieta, Island Casuals. Did you stay at the Davara or hotel in Kieta? My uncle, Bill Hallam, started Arovo Island Resort. I need to check if it was completed by 1969. I am writing a memoir of growing up on plantations in the ’50s and ’60s. Kieta was just a beautiful place, A lot of the rain trees are still there.

regards Christine