Married on the strength.

‘Camp scenes’ 1803. National Army Museum.

In 1862, when my 2nd great grandmother Emma Ponder, aged 16, married her dashing soldier Private Daniel Bailey, aged 28, his scarlet uniform had already seen over ten years of service. With the 2nd Queen’s Royal Regiment (2nd Regiment of Foot), British Army, he had fought in the Eighth Kaffir War in South Africa, and in the Third Battle of the Taku Forts and the taking of Peking (Beijing) in the Second Opium War in China. Emma, a domestic servant on a small farm outside Colchester in Essex, must have thought she’d escaped a future of drudgery, to be replaced with an exotic life in foreign places with her new husband. Officers were encouraged to marry, but for lower ranks it was a different story.

Until 1867 only 6% of Privates could marry. Those few lucky wives were considered “married on the strength” and travelled with the regiment, receiving some meagre entitlements. According to the military, marriage and family competed with a soldier’s commitment to the army. Soldiers’ pay was purposely low, being just enough to maintain the soldier, but not his family, and women were expected to work to support themselves and their children. Consequently, the army did not expect soldiers to support families left behind, thus encouraging those men seeking to evade responsibilities to sign up. During the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), many women unofficially chose to follow their men, living in women’s camps, providing domestic services such as washing, nursing, and cooking to the troops. Some women followed their husbands to the frontlines, nursing the wounded. The Battle of Waterloo in 1815 was the last battle where women played a role on the frontline.

In 1856, after the Crimean War, the military establishment was criticised for the neglect and poverty suffered by these women. The lack of soldier’s access to their families was also seen as promoting prostitution; another moral blackmark in the increasingly conservative Victorian years.

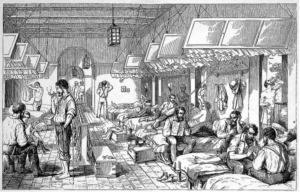

Married facilities were still poor with little privacy. Often families were separated from single men in barracks by canvas walls or curtains. Victorians were further incensed by the possibility of women being exposed to single men’s habits, illness spreading among the troops from children, and men witnessing women’s childbirth and illness.

Troops of the 2nd Queens Royal Regiment Embarking. Illustrated London News 4 Aug 1877, p 1

Applications for wives to join the regiment were only considered for long-serving ordinary soldiers on merit. Permission of the commanding officer, and at least seven years’ service was needed. By the time of Daniel and Emma’s marriage, Daniel had served for ten years, and earned four good conduct medals. In 1866 Emma followed Daniel to Ireland where the regiment was tasked with quelling civil unrest. In July that year, the regiment headed for India, and Emma, three months pregnant, boarded the troop ship with her husband.

During the long journey on a wooden sailing vessel around the Cape of Good Hope, Emma was afforded little comfort. Sea-sickness, scurvy, infectious diseases, and cramped, damp conditions awaited some of the passengers. Officers’ families enjoyed private accommodation, good food, entertainment, and time of deck, but the army, barely tolerating the presence of the Privates’ families, preferred they suffered out of sight. Their first child Daniel was born in Hyderabad in December 1866, just weeks after their arrival.

Once in India, families considered “on the strength” were required to live within the barracks, in what little accommodation was available, following the army’s rules. Quarters were to be maintained to regimental standard and could be inspected daily. Families had to attend church and the men had to remain at home in the evenings. By the time the Baileys arrived in India, newer two-story barracks had been built in some camps, but even then, the buildings were rudimentary with high ceilings, rough uncovered beams, glassless windows with shutters or iron grilles, beaten mud floors and bamboo matting; nothing to discourage rats, snakes, or scorpions. Lighting was by candles, paraffin, or coconut oil lamps. Families were still expected to share the space with the troops, often using colourful material purchased from local bazaars as curtains, for privacy. Bathroom facilities were often communal. There was no plumbing, just a tin bath filled and emptied by local servants. Married soldiers received rations for themselves but not for the family. Wives were expected to work, washing, cooking, and cleaning for the regiment. The level of the army’s distain for these women showed in the lack of even an allowance for the soap for the washing.

And then there was the heat, the rains, and the insects. Illnesses such as malaria meant early death was a constant presence. In 1880 the mortality of women and children in India was three times that back in Britain. It was difficult enough to find medical attention for childbirth, and many army wives provided the service for each other; Indian midwives considered a last resort.

Emma had three children in India, Daniel, William, and Lilley, adding to the numbers of “barrack rats”, as the children of the ordinary soldiers were called. These young children were sometimes described as “washed out little things”, besieged by fevers, enfeebled by heat and malnutrition, and exposed to cholera, and typhoid. Children died suddenly. Books were written specifically to provide advice to British parents in India, some claiming that the Indian climate could cause permanent damage to children.

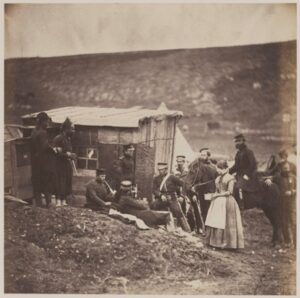

Camp of the 4th Dragoon Guards, convivial party French and English, 1855. National Army Museum.

Some schooling was available for these children, but the Bailey family left India while their children were still young. If the regiment was stationed in remote areas of India, then the children remained unschooled.

Regiments moved often, rarely in one place long enough for families to develop a sense of belonging. Wives became expert movers, hastily dismantling their homes, packing their meagre belongings, and supervising their transport on trains and carts. Bad roads and rough handling meant many packing cases were lost or smashed. Heavier items were mostly sold off before the move. Families were required to relocate with the regiment, but were not offered transport, having to find their own way, hitch a ride on a cart, or even walk.

Between 1866 and the Baileys’ departure in 1873, the 2nd Queen’s Regiment was stationed at Hyderabad, in central India, Poona (now Pune) southeast of Mumbai, and Belgaum, inland from Goa. In all three places they endured hot steamy summers and summer monsoons. Poona’s altitude provided relief from the heat at night and Belgaum was slightly cooler in summer.

Portrait of Emma Bailey 1930.

Confined within the insular society of the British in India, the wives of soldiers had little opportunity or willingness to “go native”. The wives of the ordinary soldiers were perhaps better adapted to their surroundings; adopting more comfortable clothing, acquiring goods and food from the local markets, employing Indian women to help with the children, and negotiating transport.

Emma and Daniel Bailey returned to Stanway in Essex, England, when Daniel was discharged from the army in 1873, his 21-year service earning them a well-deserved pension. Emma was still only 28 on their return and went on to have another four children, seeing them reach adulthood, perhaps employing all those essential skills she had acquired in India. Son William later also joined the army returning to India in 1889. On Emma’s death in 1930 aged 85, her family recalled her wonderful memory and the many exciting tales she shared with them of her time in India.

Sources

MacMillan, Margaret, Women of the Raj, 2018, Thames and Hudson, London BCC Library 954.03 MAC

Bamfield, Veronica, On the Strength, SLQ

https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/victorian-soldiering-wives

https://www.thesocialhistorian.com/women-and-the-victorian-regiment/

https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/blog/2018/03/16/service-in-the-british-army

https://www.queensroyalsurreys.org.uk/reg_in_india/india06_1.shtml

https://www.queensroyalsurreys.org.uk/reg_in_india/india29_1.shtml

https://www.queensroyalsurreys.org.uk/reg_in_india/india54_1.shtml

https://www.queensroyalsurreys.org.uk/reg_in_india/india50_1.shtml

https://archive.org/details/handbooktravelle00john/page/342/mode/2up?view=theater

https://punemirror.com/entertainment/unwind/air-time/cid5096298.htm

http://www.archhistory.co.uk/taca/move.html

https://www.queensroyalsurreys.org.uk/troopships/ts001.shtml

Loved this Sharyn – blending the history with your family story

This is a wonderful read. It makes me want to read more about these women. Thank you Sharyn.

Excellent blog Sharon. I enjoyed the detailed outline of the tough life these soldiers endured and how you linked it to your ancestor’s lives. They weren’t treated with much respect were they?

No, there wasn’t much respect from the authorities, but I think the rank and file appreciated their efforts. I enjoyed looking at the women’s contribution to their men’s service. It’s a great way to write women back into history. Thanks for your kind comments.

Thank you for a wonderful story Sharon. My gg grandmother was the wife of an ordinary soldier with experiences similar to your Emma. They were strong women and I am amazed at how they raised young families under such conditions. My Elizabeth died in Bendigo Victoria aged 94 after an eventful life.

Thanks Rosemary. Emma seemed to have fond memories of India, and her son returned as a soldier. It can’t have been all bad. They certainly knew how to adjust.