The wretched peasantry in Ireland: The 1822 famine disaster

By Jennifer Harrison.

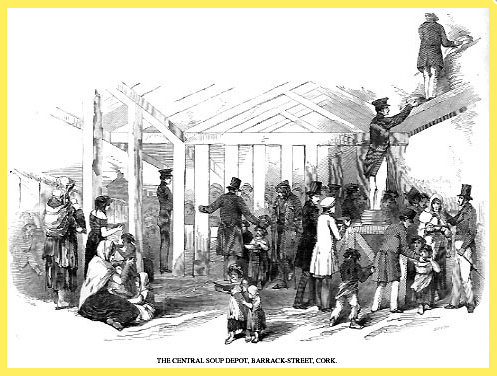

Soup Kitchen. Posted by National Famine Commemoration Drogheda 2012.

https://tinyurl.com/3pzaebb4

‘The poor Inhabitants of Clare is actily starving, living on one meal in the day and that same a bad meal, we are in hopes ye will doe something for us out of hand, we will actily Die with hunger if ye don’t luck to us out of hand as them that has a little family must Rob before They die with hunger before their face, As they are half dead before.’ This powerfully pathetic plea reported in the Caledonian Mercury on 9 May 1822 was contained in a notice fixed on the church door in Clareabbey, County Clare on the Sunday before Easter and reproduced on Friday 25 October 1822 in the Sydney Gazette. The Australian newspaper dedicated several columns to publishing details of the demoralizing famine in the west and south of Ireland quoting reports from Irish newspapers. Two hundred years ago exactly, Sydney residents were shocked to learn of the drastic plight of relatives and friends and inspired to respond by the Gazette’s final entreaty: Think of these things ye in Australasia!

Conditions were rife: eleven hundred and seventy-nine inhabitants of the parish of Clareabbey, south of Ennis, had applied for assistance amid other local suffering parishes. In the south-eastern corner of the county, at Kilfintinan and Killeely, one thousand two hundred and forty-seven were in absolute want of food, one half of whom would repay a loan while closeby at Bunratty and Dromline, six hundred and sixty-seven inhabitants were destitute of subsistence, or the means of procuring food, of whom again half would offer compensation after harvest.

The larger county divisions, the baronies, were in dire straits. That of Inchiquin surrounding Corofin had three thousand six hundred and nine individuals totally destitute of provisions, with another five hundred expected over the next month, ‘with not the most remote prospect of repaying any thing given by way of a loan’. Depressingly in Phenagh, near Bunratty, after existing on one scanty meal in the day for the last month, the dreaded typhus already had infected seven family members in just one cabin. The barony of Clonderalaw on the Shannon estuary estimated that thirteen thousand were in want of food and seed potatoes, while in the north-west of the county, in Corcomroe and the Burren, ten thousand souls needed urgent aid.

Within the Sydney Gazette’s comprehensive report, other newspapers continued the sad story. Faulkner’s Dublin Journal quoted the cost of beef and meal but deduced that ‘these prices shew that it is the scarcity of money and not of food, which distresses the people’. The reporter sympathetically protested, ‘the patience of this afflicted people is unequalled in the history of mankind, dying of hunger without committing any excess worthy of notice. A soup kitchen has been established at Ennis, for supplying the poor and its utility will extend in proportion to the amount of subscriptions’. The Courier [Dublin] indicated that Clare had received £1000 from the Dublin City Committee, the city of Limerick £500, Mayo County £500, Galway £500 and County Cork’s Skibbereen and its vicinity £100.

https://tinyurl.com/2p8pfanz AskAboutIreland and the Cultural Heritage Project

How did all this come about? Conditions developing over the years since 1818 seemed to collide in 1822-3 especially in the country’s western regions like County Clare. The British army had depended on Irish recruits to swell their ranks and following the Napoleonic Wars, from 1816 onwards unemployed soldiers returned home after the occupation of Paris, descending on their villages seeking work while recent industries, developed around beef and butter needed to feed the armies, declined. Levies on unfarmed land reclaimed for pasturage had risen during more prosperous times when out-of-work cottiers were deprived of their essential potato patches. The Irish population increasing over fifty percent between 1791 and 1821, now had reached 6.8 million with the poorer counties experiencing the greatest boom. By 1821 Clare was home to 208,084 of them. Additionally, protest groups slowly became more organized exploiting differences between war-time inflation and peace time depression, as well as deploring the imposition of Church of Ireland tithes on an essentially Catholic peasantry. Unemployment caused more disruptions than lack of food or evictions. Weather conditions were appalling and the 1821 harvest had failed.

New South Wales experienced the effect of this dreadful famine, receiving increasing numbers of those who did resort to robbery before they and their families died. The decision to reimpose the Insurrection Act and the suspension of habeas corpus from February 1822 were attempts to commute capital punishments required by current laws for such offenders to transportation across the seas. The hulk Surprize was established to house those bound for Sydney or Hobart. The late Clare historian, Dr Naoise Cleary, has estimated that only eight-two convicts, including nine women, from Clare were transported before 1822 but this number swelled to 636 by 1840, including dozens of petty thieves and agrarian insurgents.

A few of these whose trials took place during this 1822-3 disaster were numbered among the Moreton Bay recidivists. Henry Lyons arrived on the 1823 voyage of the Prince Regent, while Michael Scales and Daniel Sheehan came on Isabella 3. Of these reoffenders, Henry Lyons an insurrectionist at home, was assigned to Captain John Macarthur on arrival but after committing a robbery with violent assault in 1826 he was sentenced to serve three years at Moreton Bay. During the 1830s his criminal career continued; following the commutation of a subsequent death penalty, he was sent to Norfolk Island. Twenty-nine-year-old Michael Scales, originally from Ennis, unfortunately died at Moreton Bay during the bad summer of 1829 when over sixty succumbed to fever. Thousands more Clare men, women and families came to Queensland over the following years including orphan girls, such as the Thomas Arbuthnot ones from Ennis, Milltown and Kilmaley workhouses. Nearly all the incomers or their near relatives would well remember hardships endured before the Great Famine of the 1840s.

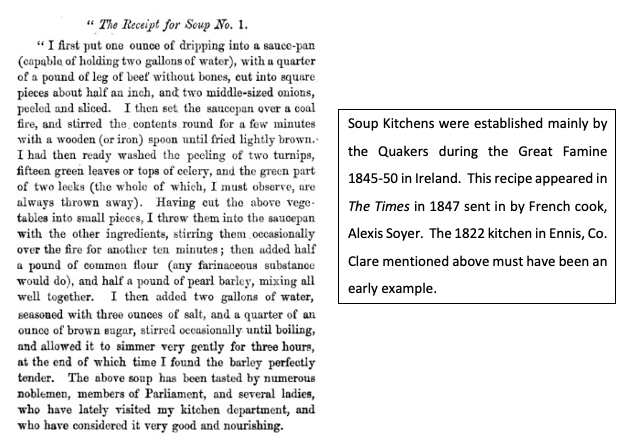

The Recipe for Soup No 1 and explanation.

The biggest shame of this famine is that it taught the ruling English nothing, allowing close to a million Irish to starve within the next 35-40 years.

Thank you, Jen for highlighting the tragic conditions during this 1822 famine about which I knew little.