Researching a Merchant Seaman.

Jack, the Legacy bear.

Finding a “mariner” in your family tree, might sometimes lead you to discover that he was in fact a merchant seaman. Other terms you might see are merchant mariner, officer in the merchant navy, merchant navy seaman, master mariner, etc. These are more often than not, some of the hardest ancestors to research, due to the fact that very few records exist. In fact, after 1858 you will not find anything until the First World War began in 1914, because the Merchant Navy did not keep any records of its seamen. There are a few reasons for this, not the least being that a total of eight government departments in the UK were at one time during the early 1800’s, in control of parts of the Merchant Navy, including the Board of Trade, the Admiralty and the Colonial Office. It’s no wonder the responsibility of record keeping was neglected. Fortunately for us, there are records dating from 1835-1857 which record the names of all merchant seamen, with some of the documents telling us a great deal, giving us an incredible glimpse into the life of our maritime ancestors.

The Merchant Navy came into being during the 17th century, when the government made an attempt to register all seafarers, in order to call them up for duty in the Royal Navy during times of conflict. Their plan didn’t work however. Merchant seamen were not happy with having to register and were suspicious of any agenda that might lead to service under duress in a royal ship, where the pay was both inferior and often delayed. There was also the issue of the living conditions aboard Navy vessels, which tended to be more cramped than those in merchant vessels which had smaller crews.

It wasn’t until almost two hundred years later, in 1835, that the Merchant Shipping Act was passed. This required all men serving in the Merchant Navy to register formally, and if called, to serve in the Royal Navy. It was now compulsory for mariners on merchant vessels to give their personal details, including place of birth, age, and often the date of their attestation or apprenticeship. Unfortunately, the system became unmanageable and was abandoned in 1857; that is why there is only a twenty-year window of records which provide information about an ancestor who was in the Merchant Navy prior to WW1.

Yet, there is plenty to find. If you discover a merchant seaman on the 1841 or 1851 census, you will have a good chance of finding him in the Registers of Seamen, 1835-1857. The originals are held at The National Archives in London, within the “BT” series of their catalogue – which in short stands for Board of Trade. Be not dismayed however, because Find My Past have digitised all the records in this series under the set titled Britain, Merchant Seamen, 1835-1857. It encompasses the following set of records from The National Archives:

- BT 120 – Register of Seamen Series I, 1835-1836

- BT 112 – Register of Seamen Series II, 1835-1844 (a name index to which is in BT 119.)

- BT113 – Register of Seamen’s Tickets, 1845-1854 (a surname index is in BT 114.)

- BT 116 – Register of Seamen Series III, 1853-1857

This is what the records will tell you:

- First and last name

- Age and/or date of birth (BT 112 gives both)

- Place of birth

- Rank/rating/role (not BT 116)

- Dates of voyages (their website has an appendix on how to interpret the information)

- Physical appearance (BT 113 only)

- Ships’ names

- Dates and ports of departure (BT 116)

- Port of ships’ registry

- notes on why the seamen left the vessel and where he went (‘how disposed of’)

Here is a sample of what you can find:

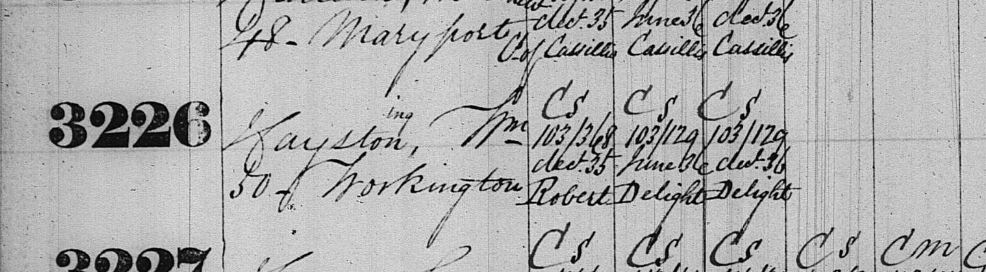

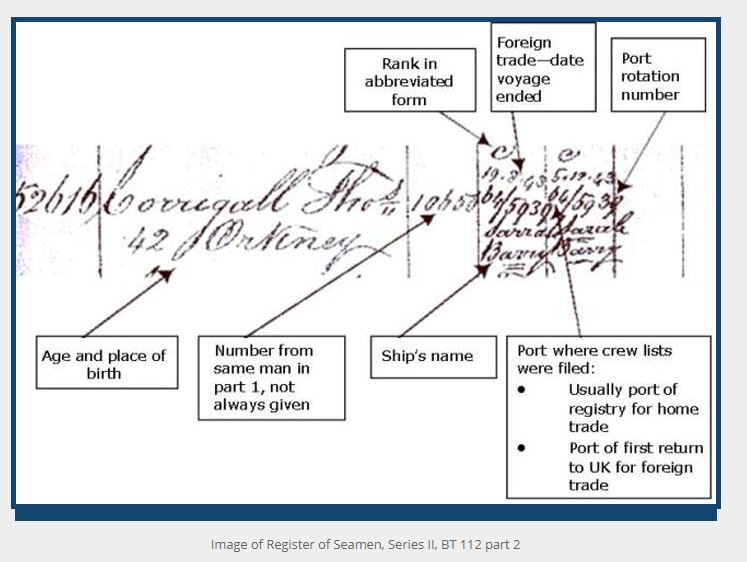

I was recently researching William Hastings, and found that he and his two sons, John and William jnr, were merchant seamen. The image above is a snippet from William Hastings’ record, dated 1835, from the digitised records on Find My Past. It records his name as William Hayston, with the letters “ing” above the “on” of his surname, showing the variant in spelling. Underneath his name is his age (50) and place of birth (Workington). The rest of the information can be interpreted using the examples given on The National Archives’ website, such as the example below.

When searching for William’s two sons, I found both of them recorded in one of the BT series as mentioned above, and digitised on Find My Past. However, because of their age and time of service, I was also fortunate to find them in two other highly informative merchant seaman record databases.

The first was the UK, Apprentices Indentured in Merchant Navy, 1824-1910 series which is indexed and digitised on Ancestry and comes from the series BT 150. As you will see on the snippet below, this told me that William Hastings jnr was indentured into the Merchant Navy on the 13th Apr 1834 in Whitehaven; he was aged 14 at the time and served 5 years under Master Joseph Hodgson.

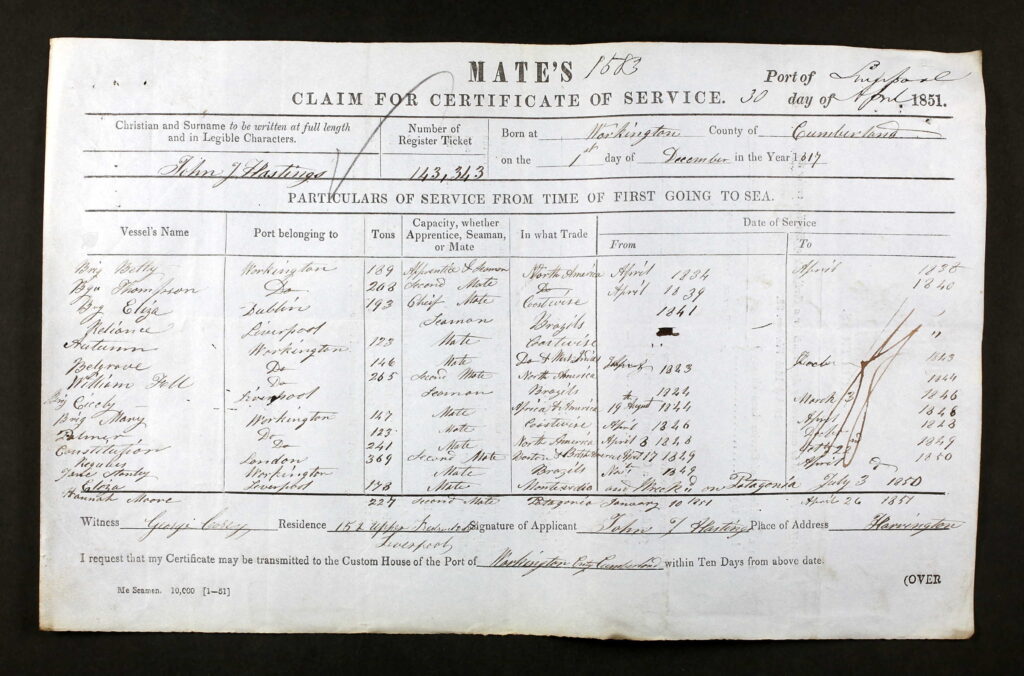

The second was the UK and Ireland, Masters and Mates Certificates, 1850–1927 series, again on Ancestry. From 1850 onwards, a merchant seaman could only be qualified as an officer if he had been awarded a Certificate of Competency by passing an exam. BE AWARE! Don’t forget to click to the “next page” when you find your ancestor’s certificate, otherwise you will only see the front page and miss the vital information on the back. I consider these records to be some of the best for telling us about an ancestor’s life at sea. As you can see below, they not only record the person’s actual date of birth, and place of birth, but also their whole life at sea. This information is what really tells the story. John Hastings, from the age of 17, served aboard merchant ships that went from his native town of Workington, Cumberland, to North America, Brazil, West Indies, Africa, Boston and British America, Montevideo, and Patagonia! The things he must have seen!

So, what was life like as a merchant seaman? During William snr’s time, the late 1790’s and into the early 1800’s, it wasn’t an easy life. When William died in 1836 he was presumed to be older than his real age, and research soon confirmed an old adage; that a seaman at the age of 45 would often be taken by his looks to be 55, or even 60. A combination of a seaman’s diet, hard work, exposure to the elements and to the ravages of ship-borne diseases, ensured that most mariners in William’s time were in poor physical shape. Long hours were common in most occupations; however, seamen had the additional burden of broken and irregular rest periods. Due to the watch stations and the system used on board most merchant vessels, William probably had no more than three and a half hours sleep at one time. Added to this, seamen were thought of as the “landless, the non-inheritors, and the underprivileged” (Alan Villiers, Voyaging with the wind, 1975). Despite merchant seamen needing a variety of skills and the fortitude and courage to take up arms when needed, they were often the forgotten in society and accorded low status.

The Hastings brothers almost certainly grew up around the docks of Workington, listening and growing accustomed to that old naval slang, colloquially known as “jackspeak”. For these boys watching and waiting for their father to come in from one of his six-monthly seafaring runs, it appeared to be a life full of adventure and comradery, and from the records uncovered, it seems that this is exactly what it came to be.

I really enjoyed this blog, Annalies. My 2G grandfather, George FILES, started his maritime career in the Royal Navy but then seemed to become a Merchant seaman. He came to Hobart and worked on whaling ships in the mid-1800s. You have provided some additional resources for me to check, if not relating to George, at least to the sort of life on the seas he might have led.

Hi Ross, and thank you for your feedback. I am so glad you enjoyed reading this and hope the additional resources provide you with a few more pieces to your genealogical puzzle 🙂 Kind regards, Annalies