What if we told the truth about how we work?

The way in which you justify your conclusions concerning a branch of your family tree has much in common with a formalmathematical proof. Each one depends upon assembling demonstrated (and defensible) facts and then proceeding from them via a path of inexorable logic to an inevitable conclusion. But they share far more than that.

Both a genealogical argument and a mathematical proof are deliberately structured to obscure the false starts, blind alleys and mistaken identifications that make each subject so fascinating to those who follow it. There is no place for the moments of extreme frustration, the daring suppositions, or the leaps of faith that play such a large part in the actual work of investigating our ancestry.

The final document does not actually describe the process we followed. There is no place in it to admit to errors and blind stabs in the dark. It describes what we wished we did, or what we would have done had we known better at the time.

Take my search for the early days of the Cameron family in Australia. I knew that Samson and Cordelia were living in Tasmania (actually van Diemen’s Land) in the mid-1830s because I had located the baptisms (plural) of their son John Samuel. But I can hardly admit in print that, driven by frustration, I resorted to a brute force search of every birth in the colonies during the relevant period to locate those records. My proof argument needs to be more “elegant” than that. If only I had their immigration record as part of the chain of evidence to justify the use of Tasmanian baptismal records.

So I turned to the names of the homes in which the Cameron families lived. That may seem an odd choice, but in the nineteenth century, there was a good chance that the name a new settler gave a home indicated a link either to their original residence in the old country (possibly a house, village or even a landscape feature) or to the ship that had brought them to this hemisphere.

The Camerons are closely associated with two significant houses in south-east Queensland. John Samuel senior built Doobawah in the Cleveland District in 1884 and John Samuel junior enlarged an existing “cottage” on Toorak Hill overlooking the Brisbane River in 1899 and renamed it Lochiel. There is a general consensus among local historians that the word Doobawah has its basis in an indigenous language. So Lochiel is my best candidate for the ship that carried Samson and Cordelia.

The Log of Logs1 has a reference to a schooner of that name that sailed between Brisbane and the Melanesian islands on the indentured labour trade during the 1880s. But such a vessel is most unlikely to have been carrying UK passengers a half-century earlier.

Lloyds Register of Ships2 contains a far more promising possibility. A 298-ton barque Lochiel constructed in 1827 for Grindley carried Lloyds’ number 398 in 1834 when captained by T. Millons on voyages from Leith to New South Wales. At that time (before the construction of the Suez Canal) voyages to what is now Australia rounded the Cape of Good Hope and so their next landfall was often Hobart Town

A search of Trove revealed a report in the Hobart Town Chronicle of 30 April 1833 that the barque Lochiel was to leave Leith for Hobart Town on 10th January. (This news would have been brought by another vessel that had recently arrived in Hobert Town after leaving Scotland later in 1832). The same paper in its edition of 14 June 1833 updated readers with the revised intelligence that the Lochiel would weigh anchor in Leith during February.

On 10 September 1833, the Colonial Times printed a list of “Vessel daily expected” on page 4 that included the Lochiel, the Scotia, and the Drummond. In its Shipping News column of 20 September, the Colonial Times finally reported: “Sept 18 Arrived the barque Lochiel from Leith 13th April with a general cargo and passengers”.

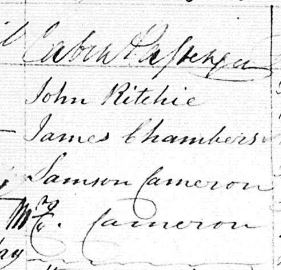

Fortunately, the bustling port of Hobart Town supported an astonishing number of newspapers and The Colonist and Van Diemen’s Land Commercial and Agricultural Advertiser on 24 September 1833 carried more extensive reports on page 2 covering Ship News3. This included the item “September 17 The bark Lochiel 298 tons Capt T, Millons from Leith 13 April with general cargo — passengers Mr. J Ritchie, Mr. James Chambers, Mr. Samuel and Mr. C Cameron and 45 in the steerage”.

Could the listed “Mr. Samuel and Mr. C Cameron” actually be husband and wife (Samson and Cordelia)? While the newspaper report was certainly contemporaneous with the event I was investigating, it is not an original record. Was I to be thwarted by simple transcription errors? I needed to examine the passenger list for myself.

The Tasmanian Archives, through LINC, provides ready access to shipping records through the Marine Board of Hobart reports of ships arrivals4. Within that series of records, item MB2/39/1/1 Reports of ships arrivals with lists of passengers 24 Mar 1829 – 25 Dec 1833 should reveal exactly the information I wanted.

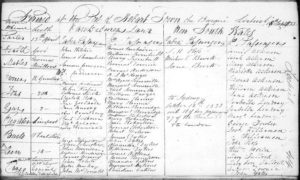

Passengers arriving aboard the Lochiel, 17 September 1883

There are 250 images in this unindexed collection but the last dozen frames contain images of a hand-written table of contents. This indicates that the Lochiel information will be found on page 414. At two pages per frame, that should be on (or about) Image 208.

Clearly, this is also not an original record. Someone has copied, by hand, information from the ship’s manifest into the habour-master’s book. But it does give an opportunity to make my own interpretation to check that of the 1833 journalist.

I am satisfied that the third and fourth listed Cabin Passengers are actually Samson Cameron and Mrs. C Cameron.

So I am now in a position to begin the formal presentation of my findings.

Samson Pearse Cameron married Cordelia Bouchier at Leominster, Hereford, England on 16 January 1833. They set sail from Leith, Scotland on 13 April 1833 aboard the barque Lochiel bound for Hobert Town where they docked on 17 September 1833. Their first child John Samuel Cameron was born in Launceston on 8 October 1834. When his son (John Samuel Cameron junior) established an elegant family home overlooking Cameron’s Rocks on the Brisbane River, he named it Lochiel perhaps in recognition of his grandparent’s epic voyage to make a new life in the colonies.

It is all true, impeccably logical with the appropriate language where speculation is involved, possibly even elegant in its construction. But that formalism obscures the enormous fun that I had in arriving at that knowledge, which I find a little sad.

References

- Nicolson, Ian Log of logs : a catalogue of logs, journals, shipboard diaries, letters, and all forms of voyage narratives, 1788 to 1988, for Australia and New Zealand and surrounding oceans, The Author jointly with the Australian Association for Maritime History, Yaroomba, Qld 1998

- Lloyd’s Register Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping Cox and Wyman, printers 1835, viewed 01 Nov 2017 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=UzoSAAAAYAAJ

- 1833 ‘SHIP NEWS.’, The Colonist and Van Diemen’s Land Commercial and Agricultural Advertiser (Hobart Town, Tas. : 1832 – 1834), 24 September, p. 2. , viewed 01 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article201158212

- Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office: Marine Board of Hobart; Reports of ships arrivals with lists of passengers, MB2/39 1829-1970

Thank you so much, Bob. What fun you had! That was a wonderful meander through a typically frustrating, time-consuming search for proof, and then the sadness of having to whittle it down to basics. Rather like their journey – so much happened along the way but you can only show what you know from records: they set out, where & when; they arrived, where & when.

Loved this story because it resonated with me. I can’t confirm the parents of my great grandfather but he named his sugar cane farm outside Mackay, Garryhill. Now this is the name of a townland in Co Carlow, Ireland (where he was married), so my investigations are continuing in that area. Sadly, I haven’t had your success as yet but, as you said, there is enormous fun in the journey.