The Irish Potato.

By Meg Carney.

Whenever Irish food is mentioned, I immediately think of the potato. I think of poverty, famine, hunger, and reliance on one food – the potato. I then think of my own family history which is intrinsically linked to the potato because a significant number of my ancestors came to Australia during the Famine of 1846 – 1851 or in the aftermath of that famine in the 1850s and 1860s.

An Irish Famine Cottage Sketch. Courtesy https://irelandxo.com/ireland-xo/news/xo-chronicles-irish-famine-sketches.

That famine is referred to as The Great Famine, The Great Hunger and The Potato Famine. It was the direct result of the failure of the potato crop several years in succession. The causes lay in the poverty and farming conditions imposed on the Irish tenant farmers over centuries.

Overtime, I have begun to wonder why the failure of one crop had such a devastating result on the population. Did their diet consist of potatoes and nothing else? If so, why? Was Ireland as a country capable of producing other crops and food to sustain the population?

The answer is, of course, yes. However, for the peasants of Ireland a variety of foods were largely unavailable to them for a century or more leading up to the Famine of 1846 – 1851. Peasants relied on the potato because it could be grown in very poor soil, and it was a high yielding crop that could feed a lot of people all year round. The Irish peasants spent most of their working hours toiling for their wealthy, primarily English, landlords. They had to sell most of the food they produced to pay rent to these landlords for the small plots of land allocated to them. They had very little time or money to provide food for their own families.

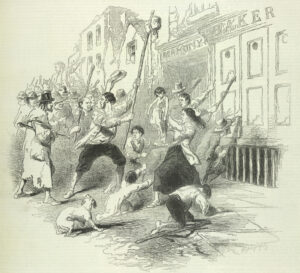

A food riot in Dungarvan. County Waterford. Ireland during the famine. 1846. Courtesy British Library. https://www.tota.world/article/264/

From earliest times the Irish were a rural agricultural people. They were hunter gatherers during the Mesolithic Age (from around 8000 BC to 4500 BC), collecting berries and hunting animals for food. During the Stone Age (4500 BC to 2500 BC), the Bronze Age (2500 BC to 700 BC) and the Iron Age (from 700 BC) they developed an agricultural system. Goats, sheep, cattle, and crops (vegetables, for example) were introduced into Ireland and as tools and weapons were developed, they were used to clear the forests for grazing cattle and growing crops.

Over the centuries Ireland continued as a predominantly agricultural country. The people were sustained by produce from the land. There was plenty of food with a staple diet of meat, fish, corn, milk, and ale, with the cultivation of crops giving added variety to these staples. Although there were continuous upheavals caused by the many invasions visited upon the Irish people as well as times of crop shortages due to bad weather, poor soil, disease, and failure to improve farming conditions, this variety of food remained plentiful until the late Middle Ages.

Ireland also had a thriving export system which had its beginnings in Ireland’s very early history. There are references in history and legend as far back as the first century AD to foreign merchants attending fairs in Ireland to trade their wines and spices for Irish hides and cloth. The Vikings who came to Ireland in the First Century AD established a trading system which continued to develop throughout Irish history. In medieval times the main exports were hides, wool and grain but salmon, hake, herring, linen, cloth, timber, butter, gold, gold vessels and ornaments were also exported. Trade continued successfully until the mid sixteenth century but then was hampered by government intervention, and the imposition of heavy tariffs. Nevertheless, trade did continue. In the 1730s there was a high demand for Irish beef and butter. The provisions trade was very successful during the Napoleonic Wars (1803 – 1815) and by the 1830s 700,000 tons of agricultural produce was exported annually.

The potato originated in the Andes. Various explorers to the Americas introduced them to the rest of the world including France and the new settlers in Virginia, America. There is a story that says that Walter Raleigh brought potatoes to Youghal in County Cork in 1585. By the late 17th Century the potato had been adopted widely in Ireland and become so popular that it replaced foods that had been eaten for centuries. The potato rich diet was not an unhealthy diet. Although over three quarters of the potato is water it also contains vitamins, fibre, and protein in a starch that does not raise cholesterol levels and is easily digested. An average size potato contains about 90 calories. If a person could eat enough potatoes and include a little milk and the occasional meat or fish a balanced diet could be maintained. The problem was that by the time of The Great Famine many people were relying on the potato as their only source of food and milk their only drink.

Potatoes generally grew in poor soil, had a high yield, and once planted required very little attention. One hectare of potatoes could produce as much food as 2 hectares of barley or 3 hectares of oats or wheat. For the Irish peasants who were being forced to exist on smaller and smaller pieces of land, this was a godsend. The potato became the stuff of folk lore and legend, celebrated in song and poetry. Many words in the Irish language evolved to describe the potato. There were words for a lumpy potato, an eyeless potato, mashed potato, a potato head, potatoes roasted in embers, worthless potatoes and more.

A potato infected with the potato blight Phytophthora infestans. Image: https://www.tota.world/article/264/

The first signs of a fungal disease in the potatoes in Ireland began to appear in September 1845. The crops started rotting in the field. Potato famines had occurred earlier in that century in 1800, 1816, 1817, and 1822. These failures did not involve the whole potato crop and were usually for one season only. The difference during the Great Famine was that the blight occurred several years in succession and because many people depended solely on the potato for their sustenance this was disastrous for the population. People did not only die from starvation. Because they were in such a weakened state of health many people died from typhus, cholera, dysentery, and scurvy which were common diseases of the day.

Ironically, during the famine years a large proportion of the land was farmed commercially to produce other crops for export. In 1847, while many people starved, an estimated 4,000 ships left Irish ports laden with food grown in Ireland. Ireland does have arable land, but it is not consistent throughout the country. The east and south-east have fertile land, the west has very poor soil and the central areas have varying degrees of arable land. The land was not divided equally amongst the population and so in the years leading up to the Famine the areas with the poorest land had the most overcrowding. Hence, these areas were the worst affected by the failures of the potato crop.

Clearly, Ireland did have the means to grow food for all its people during the famine times, but sadly, due to the social and political inequalities of those days, it couldn’t.

As an old Irish saying goes,

Potatoes are good when the white flower is on them

They are better when the white foam is on them

They are still better when the stomach is full of them.

Authors note: All information for this article was drawn from the following books:

Mike Cronin, Irish History for Dummies, Chichester, West Sussex, England, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2011.

Margaret Hickey, Ireland’s Green Larder, London, Unbound, 2019.

Ruth Dudley Edwards, An Atlas of Irish History, Abingdon and New York, Routledge, 2005.

Comments

The Irish Potato. — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>